|

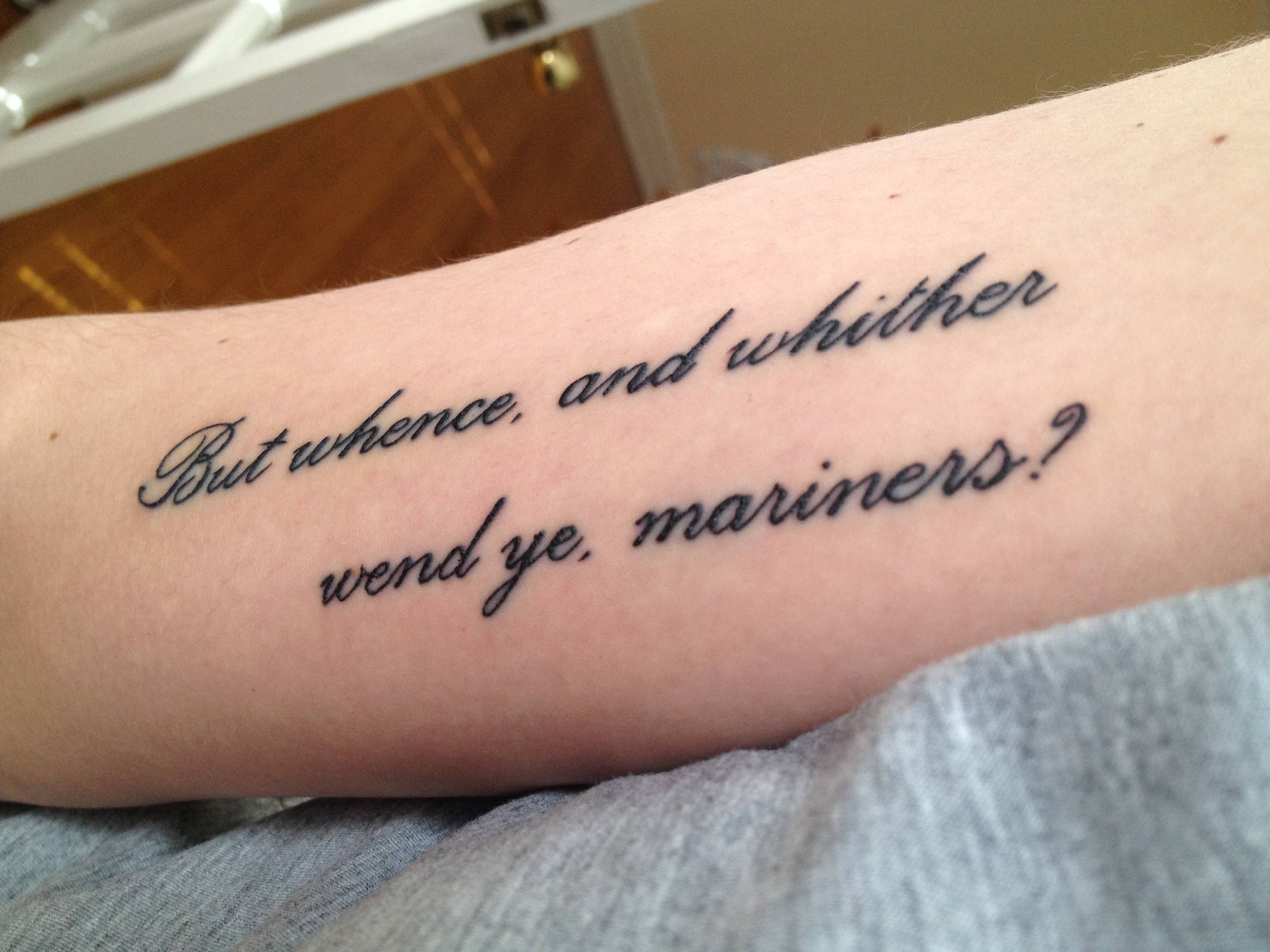

| An image search for "Mardi" yielded this tattooed quote. |

I recently came about 650 pages nearer to my goal of consuming Herman Melville in the entirety of his oeuvre by reading Mardi, and a Voyage Thither (1849).

To Melville's third book—following Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life (1846) and Omoo: A Narrative of Adventures in the South Seas (1847)—is owed the distinction of being his first true novel, which it earns through its complete desertion of factual truth. Typee and Omoo, despite their embellishments, still fall under the category of travel writing rather than fiction. But apparently some portion of Melville's audience regarded his story of being held the captive guest of an indigenous tribe in the Marquesas Islands, escaping in a leaking, shambolic whaling ship, and then bumming around French Polynesia after being brought ashore and imprisoned for his part in a mutiny, as far too outlandish to warrant credibility. Melville cites this skepticism in the preface to Mardi as the impetus which led him to try his hand at a fully fictional narrative. If his provincial readers were going to accuse him of just making shit up, then why shouldn't he fabricate a narrative and see how they like it?

As it happened, "they" didn't like it very much at all. Mr. Murr of The Lectern suggests "the Book that Cost a Career" should be substituted for "and a Voyage Thither" as Mardi's subtitle. Melville had made a name for himself with Typee, and followed it with the apt and well-received sequel Omoo. Mardi, however, received a critical mauling. Here are some excerpts of contemporaneous reviews from The Life and Works of Herman Melville:

... [I]t is almost needless to say that we were disappointed with Mardi. It is not only inferior to Typee and Omoo, but it is a really poor production. It ought not to make any reputation for its author, or to sell sufficiently well to encourage him to attempt any thing else. --Charles Gordon Greene, in Boston Post, April 18 1849

We have seldom found our reading faculty so near exhaustion, or our good nature as critics so severely exercised, as in an attempt to get through this new work by the author of the fascinating Typee and Omoo. --George Ripley, in New York Tribune, May 10 1849

This pretension to excessive novelty has in this case resulted only in an awkward and singular melange of grotesque comedy and fantastic grandeur, which one may look for in vain in any other book. Nothing is so fatiguing as this mingling of the pompous and the vulgar, of the common-place and the unintelligible, of violent rapidity in the accumulation of catastrophes, and emphatic deliberation in the description of landscapes. These discursions, these graces, this flowery style, festooned, twisted into quaint shapes, call to mind the arabesques of certain writing masters, which render the text unintelligible. --Translation of an article by Philarète Chasles, in Paris Revue des deux mondes, May 15 1849

We proceed to notice this extraordinary production with feelings anything but gentle towards its gifted but excentric author. The truth is, that we have been deceived, inveigled, entrapped into reading a work where we had been led to expect only a book. We were flattered with the promise of an account of travel, amusing, though fictitious; and we have been compelled to pore over an undigested mass of rambling metaphysics. --Henry Cood Watson, in New York Saroni's Musical Times, September 29 1849I can easily scorn the early critics of Moby-Dick (1851) for being too myopic, too cavillous, and too blinded by fashionable prejudices to realize they had the American masterpiece of the century on their hands. But I can't really knock Mardi's detractors. To put it kindly, Mardi adds up to far less than the sum of its parts. More bluntly, Melville's first foray into fiction is a real dumpster fire.

But I respect dumpster fires. They're incandescent and messy, they make for a spectacle like nothing else, and it requires a mixture of guts and madness to commit to making one. And Melville's first dumpster fire is too profuse and too exuberant not to elicit admiration.

Once you've read more than a few Melville books, you become acquainted with his peculiar habit of getting at least a hundred pages into a story and then realizing he'd rather be writing a different story. In Moby-Dick—in which Ishmael, once aboard the Pequod, ceases to bring anything to bear upon the plot and fades almost entirely except in his capacity as chronicler—it works absolutely perfectly. In The Confidence-Man (1857) the appearance of The Cosmopolitan at the novel's midpoint tosses overboard the formula and cipher that had hitherto guided the narrative, plunging the hermeneutic-minded reader into abject confusion; whether it works depends on one's assessment of The Confidence-Man as either a deceptively ingenious forerunner of postmodernism or the result of a jangled and exhausted Melville not even trying to keep it together anymore. Then there's the turn in the third and final act of Pierre (1852), where Melville abruptly decides that the titular character, in addition to being a disinherited aristocrat with a Hamlet/Christ complex, is also a successful young author (and always had been, though nothing of the sort had been alluded to previously) and uses the novel in progress to air his grievances with the entire literary industry—which, well, doesn't really work at all.

In Mardi, the transition is one from realism to high-seas romance to philosophical vaudeville show (and then a confused, perfunctory return to romance when Melville realizes he must end the book somehow, somewhere). The first twenty or so chapters would have been familiar, characteristic Melville to an 1849 audience. A young sailor on his third year of a whaling voyage decides he'd strongly prefer not to spend another three years cruising the Arctic Sea for victims. He conspires with a seasoned shipmate to steal a boat under cover of darkness and take to the open seas on a due west course for the Gilbert Islands. Here Melville cleaves to the habits he cultivated in Typee and Omoo, illustrating the sights, conventionalities, and hazards of the South Pacific for a landed, literate audience. He peppers his alacritous prose with nautical terms and descriptions of the various appurtenances of maritime life and their uses, and interpolates some truly wonderful textual sketches of sea creatures between the chapters which advance the plot.

By and by we progress to the novel's intermediary metamorphosis, where it takes the form of a nautical drama. The narrator (unnamed for now) and his companion (Jarl) explore a ghost ship, befriend a one-armed savage (to use Melville's parlance) and his termagant spouse, and brave a deadly tropical cyclone. Later on they encounter a seafaring party of local islanders from whom they abduct a mysteriously fair-skinned maiden marked as a human sacrifice, murdering the entourage's high priest in doing so. Afterwards they arrive at a large island in a tropical archipelago hitherto unknown to Western cartographers. The archipelago is called Mardi; the isle is Oda, and its king is the self-styled demigod Media. Our narrator ingratiates himself to the the people of Oda and their nominally divine chieftain by proclaiming himself the deity "Taji," recently returned from a visit to the sun. (Our narrator, conveniently, can speak and understand the languages of Polynesian peoples.)

And so for some days and weeks our narrator (henceforth named Taji for all intents and purposes) enjoys the royal hospitality of King Media, and luxuriates his nights and mornings in a private thatched bungalow with Yillah, the otherworldly girl he rescued from sacrifice by kidnapping her from her people. At this point, we're on chapter 63 of 195.

|

| Paul Gaugin, "Two Marquesans" (1902?) |

One morning, Yillah vanishes without a trace. Unable to find her anywhere on Oda, the aggrieved Taji declares to Media his intent to to search for her throughout the neighboring islands. Not only does Media furnish Taji with four ample canoes, teams of rowers, and a supply of food, wine, and tobacco, but elects to accompany Taji personally. And he brings with him the historian Modi, the philosopher Babbalanja, and the bard Yoomy. (Jarl and the one-armed Samoa accompany Taji too, though their presence in the story is indeed becoming parenthetical. Oh, and Samoa's wife died at sea, but nobody remembers anymore.)

The party rows from island to island, inquiring after Yillah. They visit the isle of Juam, where a taboo confines the king to his palace, never permitting him to see or walk the lands constituting his domain. They pass Ohonoo, "the isle of rogues," founded by Mardi's outcast scoundrels and criminals, evolved over time into a virtuous and functional society that yet celebrates the character of its progenitors. They feast on the island of Mondoldo, where the radically hospitable King Borabolla has conscientiously eschewed all gates and walls.

Meanwhile: Mohi recites chronicles, Babbalanja philosophizes, and Yoomy sings (transcribed as truly embarrassing doggerel verse) in a nautical symposium moderated by Media, while Taji stops saying or doing much of anything. The travelers are haunted by the periodic apparition of three women bearing tokens of beckoning and foreboding from the enigmatic Queen Hautia, and stalked by three survivors of the melee which precipitated Yillah's abduction.

When the company departs from Mondoldo, Jarl and Samoa elect to stay behind. Samoa is never mentioned again. Some time later, messengers send word of Jarl's murder at the hands of Yillah's avengers. With his death, the novel severs not only its last tie to the world outside Mardi, but to any believable verisimilitude of reality. Melville starts forgetting that Mardi's people are of an isolated Polynesian culture; Media's roving symposium mentions European figures and deities, visits libraries, and puns in English.

The narrative turns transparently satirical as the party visits the island of Diranda, whose rulers have instituted gladitorial games as a hedge against overpopulation, and Minda, where the activities of a guild of mercenary sorcerers bear no small resemblance to the paper-serving lawyers of the English-speaking world. With the appearance of the islands of Dominora and Kolumbo, Mardi (the archipelago) turns to a South Seas miniature of Christendom, and Mardi (the novel) routinely prompts groans of "oh, Herman." For you see, Kolumbo—said to be the archipelago's last discovered island—is home to the nation of Vivenza: a former colony of the naval power Dominora that recently won its independence, and now conducts itself as a free state without a ruling monarch. Tensions simmer between the northern and southernmost territories of Vivenza over the latter's reliance on agricultural slave labor. The western side of Kolumbo is inhabited by gold miners; the island's northern extremity, Kanneeda, remains in Dominora's thrall. And we also learn of the isles of Franko (France), Ibeereea (Spain), Vatikanna (the Vatican), Muzkovi (Russia; its monarch is said to rule over millions of acres of glaciers in the north, even though we're to understand Mardi is in the South Pacific), and one starts to wonder if Mardi was subject to any sort of editorial scrutiny before being typeset and sent to the presses. Melville, vacillating between his commitment to the burlesque in which he is now waist-deep and his ardency for The Quest, narrates the circumnavigation of Kolumbo and the excursion into Mardi's westerly lagoons with a buoyant exhilaration, as though it really were a voyage 'round the globe.

Mardi's climax and conclusion are completely half-baked and warrant no summary. To substantiate any claim of a consonance between the bulk of the novel and its rushed ending would require some real hermeneutic jiu-jitsu, and neither I nor this informal overview are up to the task.

|

| Paul Gaugin, Montagnes tahitiennes (1891) |

If Melville had heeded his most acerbic critics and gave up his literary career after Mardi, the book wouldn't be half as interesting as it is. By itself, it's a discordant, confused, and ultimately unsuccessful experiment by a twenty-something author flying completely by the seat of his pants. Whatever redemptive virtues it possesses in and of itself follow from Melville's raw and immense talent as a prose stylist. For such a hot mess, Mardi is astonishingly well-written. But it is nevertheless a hot mess, and probably wouldn't be worth the time and effort to read if its author weren't the same Herman Melville who wrote Moby-Dick, and if its pages weren't so rife with foreshadowings of his later work. As the archipelago called Mardi expands to a microcosm of Melville's world, the novel Mardi can be judiciously treated as an encapsulation of his oeuvre.

As Mardi's main narrative comprises the philosophical conversations of a group of archetypical pilgrims (the king, the historian, the sage, and the poet), the novel most resembles Clarel (1876) in its blueprints, if not its temporal and metaphysical concerns. (Ironically, where Mardi's downfall is a total lack of authorial self-restraint, the epic poem Clarel is far too fettered by the restrictions of form to reach the heights Melville attained in his prime.) In the details of its execution, Mardi anticipates Moby-Dick. Taji, like Ishmael, comes onto the stage as the figure whose personal agency and intercourse with others ordains the story's course, and he diminishes to the stature of a mere spectator once Melville introduces characters whom he finds he's more eager to write about—Media and Babbalanja in particular. Taji's obsessive quest for the ivory-skinned Yillah contains a germ of Ahab's monomaniac hunt for the White Whale, but in divesting from the adventure's driver the privilege of participation in its events, Mardi reduces its own plot to a background detail. Melville will amend this mistake in Moby-Dick, transferring the identity of the seeker to a combination of the figures typified in Media and Babbalanja: indeed, Ahab can be loosely interpreted as a union of the the godlike authority figure and the demon-possessed philosopher we meet in Mardi.

The attentive and exhaustive Melville reader will undoubtedly spot threads linking Mardi and its paeans to feasting, imbibing, and smoking (notably, always and only with members of the male sex) to "The Paradise of Bachelors" (1855) and Moby-Dick's Peruvian interlude. Apparently there were few things Melville savored more than sharing conversation and epicurean indulgences with men of stature and erudition, and one suspects he didn't do it nearly as often as he would have liked. (Was Melville gay? "Probably not," says Robert McCrum. "Bisexual? Almost certainly.") Probably not coincidentally, the strained relationship between Samoa and his willful dame Annatoo cues Melville to crack wise about the preferableness of bachelorhood to matrimony in a novel published two years after the start of his fraught marriage to Elisabeth Shaw. (I'm not sure that the Melville who wrote Typee or Omoo would have thought to call a becalmed sea "more hopeless than a bad marriage in a land where there is no Doctors' Commons [divorce court].") Readers wishing to psychoanalyze Melville's thoughts and inclinations toward the opposite sex will find ample material in the figure of Yillah, whose unsettling otherworldiness, distressed helplessness, and the dubious account of her origins prefigure Isabel from Pierre, as does Taji's adoring and self-destructive devotion to her.

Tellingly, what Mardi in no way anticipates is the weary cynicism of The Confidence-Man. The Melville who wrote it had not yet been Timonized; the Canada thistle had not yet taken root in his own soul. He writes with verve and vigor, and thrusts out beyond himself with the confident, all-embracing promiscuity of a Walt Whitman. His inspired prose churns and leaps with a half-wild ecstasy scarcely found in either Typee or Omoo—or, for that matter, in anything he wrote after Pierre. This is that Melville whom we recognize from Moby-Dick, irrepressibly given to reverie and parable, who seems like all he can do is clutch his frantic pen and try to keep it from flying off ahead of him or burning a frictive hole in the page.

No other moment in Mardi exemplifies Melville's tremulous awakening to his own powers more than the fifteenth chapter of the second volume (chapter 119 overall), called "Dreams," transcribed below (copy/pasted from Project Gutenberg.) Context? You don't need any. This chapter is completely unrelated to the episodes that come before and after. It not so much an authorial digression so much as an unsurpressed eruption.

Dreams! dreams! golden dreams: endless, and golden, as the flowery prairies, that stretch away from the Rio Sacramento, in whose waters Danae's shower was woven;——prairies like rounded eternities: jonquil leaves beaten out; and my dreams herd like buffaloes, browsing on to the horizon, and browsing on round the world; and among them, I dash with my lance, to spear one, ere they all flee.

Dreams! dreams! passing and repassing, like Oriental empires in history; and scepters wave thick, as Bruce's pikes at Bannockburn; and crowns are plenty as marigolds in June. And far in the background, hazy and blue, their steeps let down from the sky, loom Andes on Andes, rooted on Alps; and all round me, long rushing oceans, roll Amazons and Oronocos; waves, mounted Parthians; and, to and fro, toss the wide woodlands: all the world an elk, and the forests its antlers.

But far to the South, past my Sicily suns and my vineyards, stretches the Antarctic barrier of ice: a China wall, built up from the sea, and nodding its frosted towers in the dun, clouded sky. Do Tartary and Siberia lie beyond? Deathful, desolate dominions those; bleak and wild the ocean, beating at that barrier's base, hovering 'twixt freezing and foaming; and freighted with navies of ice-bergs,——warring worlds crossing orbits; their long icicles, projecting like spears to the charge. Wide away stream the floes of drift ice, frozen cemeteries of skeletons and bones. White bears howl as they drift from their cubs; and the grinding islands crush the skulls of the peering seals.

But beneath me, at the Equator, the earth pulses and beats like a warrior's heart; till I know not, whether it be not myself. And my soul sinks down to the depths, and soars to the skies; and comet-like reels on through such boundless expanses, that methinks all the worlds are my kin, and I invoke them to stay in their course. Yet, like a mighty three-decker, towing argosies by scores, I tremble, gasp, and strain in my flight, and fain would cast off the cables that hamper.

And like a frigate, I am full with a thousand souls; and as on, on, on, I scud before the wind, many mariners rush up from the orlop below, like miners from caves; running shouting across my decks; opposite braces are pulled; and this way and that, the great yards swing round on their axes; and boisterous speaking-trumpets are heard; and contending orders, to save the good ship from the shoals. Shoals, like nebulous vapors, shoreing the white reef of the Milky Way, against which the wrecked worlds are dashed; strewing all the strand, with their Himmaleh keels and ribs.

Ay: many, many souls are in me. In my tropical calms, when my ship lies tranced on Eternity's main, speaking one at a time, then all with one voice: an orchestra of many French bugles and horns, rising, and falling, and swaying, in golden calls and responses.

Sometimes, when these Atlantics and Pacifics thus undulate round me, I lie stretched out in their midst: a land-locked Mediterranean, knowing no ebb, nor flow. Then again, I am dashed in the spray of these sounds: an eagle at the world's end, tossed skyward, on the horns of the tempest.

Yet, again, I descend, and list to the concert.

Like a grand, ground swell, Homer's old organ rolls its vast volumes under the light frothy wave-crests of Anacreon and Hafiz; and high over my ocean, sweet Shakespeare soars, like all the larks of the spring. Throned on my seaside, like Canute, bearded Ossian smites his hoar harp, wreathed with wild-flowers, in which warble my Wallers; blind Milton sings bass to my Petrarchs and Priors, and laureats crown me with bays.

In me, many worthies recline, and converse. I list to St. Paul who argues the doubts of Montaigne; Julian the Apostate cross-questions Augustine; and Thomas-a-Kempis unrolls his old black letters for all to decipher. Zeno murmurs maxims beneath the hoarse shout of Democritus; and though Democritus laugh loud and long, and the sneer of Pyrrho be seen; yet, divine Plato, and Proclus, and, Verulam are of my counsel; and Zoroaster whispered me before I was born. I walk a world that is mine; and enter many nations, as Mingo Park rested in African cots; I am served like Bajazet: Bacchus my butler, Virgil my minstrel, Philip Sidney my page. My memory is a life beyond birth; my memory, my library of the Vatican, its alcoves all endless perspectives, eve-tinted by cross-lights from Middle-Age oriels.

And as the great Mississippi musters his watery nations: Ohio, with all his leagued streams; Missouri, bringing down in torrents the clans from the highlands; Arkansas, his Tartar rivers from the plain;——so, with all the past and present pouring in me, I roll down my billow from afar.

Yet not I, but another: God is my Lord; and though many satellites revolve around me, I and all mine revolve round the great central Truth, sun-like, fixed and luminous forever in the foundationless firmament.

Fire flames on my tongue; and though of old the Bactrian prophets were stoned, yet the stoners in oblivion sleep. But whoso stones me, shall be as Erostratus, who put torch to the temple; though Genghis Khan with Cambyses combine to obliterate him, his name shall be extant in the mouth of the last man that lives. And if so be, down unto death, whence I came, will I go, like Xenophon retreating on Greece, all Persia brandishing her spears in his rear.

My cheek blanches white while I write; I start at the scratch of my pen; my own mad brood of eagles devours me; fain would I unsay this audacity; but an iron-mailed hand clenches mine in a vice, and prints down every letter in my spite. Fain would I hurl off this Dionysius that rides me; my thoughts crush me down till I groan; in far fields I hear the song of the reaper, while I slave and faint in this cell. The fever runs through me like lava; my hot brain burns like a coal; and like many a monarch, I am less to be envied, than the veriest hind in the land.

No comments:

Post a Comment