Every text builds on pretext.

—Walter Ong, Orality and Literacy (1982)

About a year ago, YouTube's mysterious, incontrovertible algorithms served me a video titled "The Zelda CDi Reanimated Collab!" I don't suppose the recommendation changed my life, but good god—I watched it enough times to inadvertently memorize most of the dialogue, and I'm fairly sure this is something I ought to be ashamed of.

Probably most people who'd peer at this crusty old blog are old enough to remember the 1993 CD-i Legend of Zelda games—even though they've almost certainly never played them. During the early-to-mid 2000s, when the internet acquired its voracious appetite for the grotesque, Link: The Faces of Evil and Zelda: The Wand of Gamelon were a phenomenon on the message boards and pop culture excavation blogs. But for anyone who isn't familiar: in 1990, the Dutch electronics company Phillips released a home console that ran software and games formatted on proprietary compact discs. Due to some legal agreements made during the CD-i's development (it's complicated), Phillips found itself with a license to make games featuring copyrighted Nintendo characters. In its most well-known attempt to capitalize on this arrangement, Phillips outsourced the production of two legitimized bastard Legend of Zelda games to the Russian-American studio Animation Magic, providing scant resources and demanding an exacting turnaround time. And the rest is infamy.

To put it exceedingly gently, Faces of Evil and Wand of Gamelon weren't very good. But what stoked the internet's delirious fascination with them wasn't the third-party jankiness of their action-adventure molds, but their full-motion video cutscenes. The animations, produced by a Russian team flown over to the United States, beggar description. The words "flat," "uncanny," "maladroit," and "charmless" all come to mind, but none really approach how astonishingly ugly these FMVs are. Combined with their hammy voice acting, obtuse dialogue, and very fact of their inclusion in games that brazenly sold themselves as authentic Legend of Zelda sequels, CD-i Zelda's cutscenes transcend mere ineptitude. They are sublimely embarrassing—a thoroughgoing and wholly avoidable blunder on the order of the Borja Ecce Mono.

The Zelda CDi Reanimated Collab is self-explanatory: some two hundred artists and animators reworked all the FMVs from Faces of Evil and Wand of Gamelon, scene by scene and shot by shot. Many of the new animations are deliberately goofy; others present their material more or less in earnest, and several achieve the remarkable fear of obscuring the ridiculousness of the source material. Memes abound throughout, befitting a tribute to a game that provided the basis for a slew of absurdist internet in-jokes. Some contributors are animators whom we can only hope will have a future in the field (if they haven't gone pro already); others are clearly hobbyists or students having a little fun. Without exception, every scene is an improvement over the original.

I've watched this damn thing over a dozen times in the last year. I showed it to my former roommate Madalyn and her buddies from art school. We all agree that it's just delightful.

Apparently reanimation collabs are Kind Of A Thing on YouTube. Here's a very early one: the Pokemon ReAnimated Intro collab. And here's The Dover Boys ReAnimated Collab. The Bartman Reanimate Collab [sic]. The WarioWare Gold Reanimated Collab. And so on.

I haven't viewed any of these in their entirety, and I doubt I will. As much as I appreciate joint efforts by enthusiastic amateurs, a 1942 Chuck Jones classic didn't really need a crowdsourced digital reimagining. The CDi Zelda Reanimated Collab is interesting to me precisely because an affiliation of (mostly) nonprofessionals reworked a licensed commercial product developed by "actual" animators, and made it irrefutably better.

Today I'm interested in examining it not as a funny YouTube video, but as a neoteric cultural artifact. Despite how unextraordinary it existence may seem to anyone for whom the web was always a mere fact of life, the CDi Zelda Reanimated Collab (and anything like it) would have been impossible twenty years ago. Forty years ago, it would have been unimaginable.

Let's try to understand the conditions that made this thing possible, and then attempt to determine what meaning we might ascribe to it, or what it might tell an alien anthropologist about us. I mean, it's not like I had anything else going on this afternoon.

MEDIA: THE EVAPORATION OF ART

Since, Excellenza, you insist, know that there is a law in art, which bars the possibility of duplicates.

—Herman Melville, "The Bell Tower" (1855)

Well, what is art?

Yes, yes—here we go again.

E.H. Grombrich begins The Story of Art (1950) with the sensible answer that there really isn't such a thing as art—there are only artists. As examples of this peculiar subspecies of Homo sapiens, Grombrich cites ancient men who smeared earthen pigments on cave walls, twentieth-century men who paint of advertising posters, and by connotation, everyone else who received socially mediated reinforcement for the behavior of dabbing colored ooze on a surface between the Stone Age and the Atomic Age.

So we've narrowed it down: whatever artists make, it's things. Art is stuff. John Ruskin, Fernand Léger, John Berger, and other old-school authorities I can pull from my bookcase concur with Gombrich in taking the materiality of art as a given.

So, we have as our examples of art: an oil painting of a clothed and/or nude maja on canvas; a statue of a sleeping satyr chiseled from a slab of marble; a pencil drawing of an English landscape; an amphora with black-figure depictions of Achilles and Ajax playing chess on its side; one urinal chosen from a hundred thousand dittos, placed on a plinth, and signed "R. Mutt;" and so on.

What purpose do any of these objects serve?

Depends on what it is, and where and when it was made. If we're looking at strokes of ochre and charcoal on a cave wall approximating the likeness of a bison or deer, we can reasonably guess that painter meant to magically enervate or control the animals he or she depicted. If it's an image of the Egyptian deity Osiris painted on the wall of a tomb, the painter was very likely employed as a sort of investment agent, dutifully striving to ensure the felicity of his ruler in the afterlife. A altarpiece painted in fifteenth-century Normandy would have been fashioned in order to make visible the the people and concepts of the Christian religion during liturgical rituals. An oil painting of a landscape by some famous Impressionist or other was made to earn income for the painter in a manner that was stimulating and gratifying to him, and to look attractive on a wealthy person's wall and impress his guests. The fresco on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and the stainless steel sculpture of a balloon animal in the lobby of an Astor Place office building leased to IBM are both there to signal institutional wealth and power.

As tools, most of these would be pretty useless, or a least not very helpful. There are more effective objects one could reach for than a Monet canvas if one wished to hammer a nail, turn over dirt, bludgeon an intruder, transport a gallon of water or a bushel of grain, etc. We can make a tentative distinction between an object that is meant to be beautiful and mechanically useful (like a load-bearing caryatid or a stained glass window) and the "pure" aesthetic object, which is made because of its effects upon people, who confront it as packet of visual stimuli.¹ Whatever the things does, it does it inertly.

The same could be said of a written manuscript or printed book: they are physical objects made in such a way as to elicit a response from somebody. The fact that the viewer must physically manipulate the object (pick it up, turn the pages) to use it is a minor detail here, as is the difference between the pictorial visual stimulus and the abstract verbal visual stimulus. Whether we're in a gallery looking at a Braque still life of a fruit dish, or paging through a copy of Jean Baudrillard's The Conspiracy of Art (2005) outside the museum's gift shop (where our girlfriend is inspecting every individual postcard for sale), the "content" with which we are engaging exists in the simultaneity of the thing's concrete and temporally persistent integrity.

Notwithstanding the comparative "density" of the verbal stimuli printed on a page of the book, the viewer (user?) of the Braque canvas or the Baudrillard text encounters each object in itself as the invariant prompt to a response pattern. (The provision "in itself" is worth adding insofar as the context in which each is experienced can't be said to be invariant. Details.) The viewer's roving attention—scanning sentences or focusing on one area of the painting and then setting her gaze upon another—constitutes the "experience" of the thing, whether she is "hearing" the words printed or drifting in a reverie of aesthetic contemplation.

|

| Georges Braque, Fruit Dish and Glass (1912) |

QUESTION #1: Aren't you forgetting an important difference between the oil painting and the paperback book: one is a one-of-a-kind handmade work, and the other is a mass-produced duplicate. Shouldn't we be taking this into account?

Sure. Considered strictly as static packets of visual stimuli, an oil painting produced by Kandinsky in the 1920s and an offset-printed reproduction that shipped last week might have many more obvious similarities than differences. But here we're interested in the socio-technological paradigms which determined the creation of each.

We can take ancient Rome as a (completely arbitrary) historical starting point. The Romans were just crazy about Greek sculpture, and shipped plaster casts of statues to workshops all across the Empire, to be used as copying templates. Reproduction remained a labor-intensive operation, whether the reproduction was in bronze, made through the lost-wax method, or in marble, made by a sculptor using a labeled cast as a reference. Cheap terracotta figurines could be mass produced by the use of pre-fabricated molds, as could ceramics; decorative relief work on fine wares could cheaply and efficiently added with the use of a stamp. These, however, would not have been prized as objets d'art—and evidently the Romans were less enamored of the Greeks' superbly painted ceramics than they were of their statuary.

In theory, paintings would have been much more difficult to reproduce—but very few Roman paintings remain, and we have too little documentary evidence to know very much about their production, sale, etc. Frescos would have been painted on commission, and not easily copied. Ditto mosaics. Some wood panel paintings—particularly of the emperor, whoever he was at a given time—were mass produced by hand, probably from a template, but we can't say much else about them. Possibly the workers (or slaves) who churned them out strove for as high a degree of consistency as could be achieved, but as Melville says, exact duplicates in handicraft are impossible.

A Roman writer who wished to write and disseminate a book among his fellow patricians relied on slaves to turn out handwritten copies. These would be given as gifts to friends. With the author's permission, those friends could have copies made, at their own expense, if it pleased them to do so. If an author donated a copy of his book to a library, the text was fair game for anybody who wished to make a transcription and take it home with them. (The libraries of antiquity were far less generous about loaning books than ours are today.) If an author didn't wish for his work to circulate beyond its first readers, or if a book's recipients believed it wasn't significant enough to warrant the expenditure of having a copy made (or making one themselves), its production run was over.²

The themes here: three-dimensional aesthetic objects are relatively easy to replicate and manufacture en masse, provided they're composed of a single inexpensive and malleable material (such as clay). Paintings and literary works, however, were not much easier to copy than to create in the Roman Empire, since it all had to be done manually.

Antiquity regarded visual art-objects as decorations, treasures, and curios whose value lay precisely in their beauty, and in their capacity to communicate power. As repositories of information, codices were valuated in terms their contents, which could be useful as resources to the learned. In medieval Europe, a book could be a priceless thing. Even if there were several known copies of a particular work, tracking any of them down could be difficult, and could entail long and possibly dangerous journeys. If a library was burned down by marauding invaders, any texts without extant copies elsewhere was erased from existence, lost forever.

The ease with which handwritten letters could be substituted by the impressions of moveable type positioned the book to become the first art-object to be transformed by a mechanized production process, and to be guided in its further development by the economic incentives of large-scale manufacture and the stoking of public demand. One consequence of the Gutenberg revolution was the diminution of the book's status as an art-object, a handcrafted treasure. It became nothing more nor less than a manufactured article.

|

| From the Ellesmere Chaucer Manuscript (ca. 1400). Considerably prettier than the page on which the same passage appears in my Penguin Classics edition. |

Two-dimensional visual art was slow to follow literature into the maw of serial manufacture, but a change in the circumstances of its production was nevertheless underway in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with the Netherlands at the fore. Having grown wealthy from domestic industry, overseas trade, and their colonial ventures in the Americas, Dutch burghers' newfound appetite for luxuries previously reserved for the church and nobility opened a new market for artists.

Walter Benjamin, Peter Bürger, et al. elucidate the process by which the proto-capitalist stirrings of mercantilism pried visual art loose from its institutional fetters The use-value of an objet d'art came to reside partially in its movability: unlike the frescoes and mosaics preferred by the upper crust of ancient Rome, the art favored by the emergent bourgeoisie could be purchased, hung on a wall, moved to another wall, and then sold for a tidy sum to somebody else who can display it howsoever he pleases in his home, place of business, vacation spot—wherever—with no fuss, no ritual observance, or risk of sacrilege.

The emergence of a commercial art market required (and advanced) the phenomenon of modernization which Bürger called the "apartness of the work of art from the praxis of life." In this regard, the painting exhibited in an art gallery is the exception that proves the rule. Imagine if the Braque still life we were admiring earlier weren't enshrined in the secularized sacred space of a Guggenheim or Louvre; let's also pretend that Braque's career never took off, posterity regarded him as an unremarkable also-ran among the Cubists, and we've never heard of him before. How would we regard that same painting if we found it on the cluttered living room wall of our eccentric, antique-hoarding aunt? Would we pause before it in reverent contemplation? Probably not. We'd probably just be pleased to notice that it matched Auntie's furniture.

A critical difference between Michelangelo's frescos in the Sistine Chapel and the stainless steel balloon animal in the lobby of 51 Astor Place is that the owner of the Manhattan office building acquired the Koons sculpture not just for its use as a symbol of wealth and prestige, but as as a transactable asset expected to appreciate in value.³ A work of art produced for the art market may come to rest in a certain place for a certain period of time—but its reason for existence is to be bought, sold, and circulated.

As Fine Art ascended in social importance as a fetishistic token of status and taste (and one's taste was an indicator of one's morality, and one's morality vindicated one's status), enterprising tradesmen realized the lucre that was to be earned from producing printed reproductions of famous artworks. It is a truism that the lower classes wish for the fineries enjoyed by the rich, and are willing to accept inferior facsimiles, yes—but even a nineteenth-century aesthete of means or an art student from a well-to-do family had use for printed "versions" of painted masterpieces. One who professed to know art had to understand what people were talking about when they talked about Titian, and seeing his paintings entailed traveling the continent (as had once been the case for a monk who needed to consult a text that his abbey's library lacked). After arriving in Paris, Rome, or Venice and visiting a gallery exhibiting Titian's work, he was apt to find himself in a chamber packed with his fellow pilgrims, all murmuring, shuffling, and vying for a better view—not the most conducive environment for prolonged scrutiny and concentration.

In one respect, art reproductions manufactured from an engraved or etched plate used essentially the same technology which turned out copies of printed literature by the heap. On the other hand, the methodology was still imperfect. Gutenberg's breakthrough lay in the realization that any written text could be disintegrated into and rebuilt from the individual letters of the phonetic alphabet, but paintings were far more resistant to being reduced to a finite set of standardized atomic components. Moreover, the impossibility of perfectly reconstructing an oil painting with monochrome linework, however steady the craftsman's hand and sharp his eye, meant that many travelers were surprised to discover that Raphael's Marriage of the Virgin looked nothing like their books had led them to expect.

Nevertheless—just as the work of translating a novel or volume of poetry from one language to another is a form of literary composition unto itself, interpreting a variegated painting with linework alone was no small artistic feat.

As prints based on handmade engravings and etchings approached the limits of what could be realistically expected of their verisimilitude to original artworks, an insurgent technology—photography—was making powerful strides. Art historian Trevor Fawcett explains:

Around 1850 a series of improvements transformed photographic technology——the albumen print, the use of bromide as a developing agent, and, most crucial of all, Scott Archer's wet-plate collodion process, which sharply reduced exposure and development times without loss of fine detail. Further discoveries soon set forth the principles of stereoscopy, the dry-plate process, permanent (carbon) prints, the sensitizing of metal, stone and wood printing surfaces, and——to await later application——photogravure, photolithography, and collotype. It was among photography's most technically creative periods, stimulating increased activity on many fronts, and not least in the photography of subjects like paintings which had hitherto proved intractable. Comparisons could be made at last between hand and machine as reproductive instruments.⁴

Fawcett explains that photography lagged behind engraving, etching, and lithography as the basis for reproductive printing due to its "inability to handle colour, its difficulties with reflections and high-lights, the impermanence of its prints, and its continued incompatibility with the printing press."

But the new technology swiftly closed the distance. By the end of the century, the development of effective and economical photomechanical processes—Woodburytype, photogravure, and halftoning—brought a degree of fidelity to printed reproductions of artworks that intaglio methods simply couldn't attain.

The success of halftone printing—the technique by which a photograph could be rephotographed onto a light-reactive plate for high-volume print runs—recapitulated Gutenberg's grand epiphany. Just as a written text could be atomized into its (literal) building blocks, so too could visual data—as dots. An engraver already had some inkling of this, "translating" different shades and intensities of color with varying densities of fine linework, but the accuracy and efficiency of photomechanical process placed him in the same unenviable position the career portrait painter had found himself in after the popularization of the camera.

Though halftoning was more often chosen for its economy and efficiency rather than image quality, it was a conceptual stepping stone toward RGB and CMYK printing—which are now, of course, ubiquitous. Everything is made of tiny dots, from the run-on sentences in a Faulkner novel to the photographic image of a politician on the front page of USA Today to the full-page reproduction of a Braque still-life in Auntie's coffee table book to a Jack Kirby splash panel to a magazine ad for Absolut vodka to the Pokémon poster you had framed for some reason...

The epilogue to this condensed narrative can be found inside the gift shop of my former employer, the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The institution has made a small fortune selling postcards, posters, tote bags, umbrellas, pencil cases, puzzles, etc. emblazoned with high-fidelity reproductions of paintings from its renowned Impressionist collection. Van Gogh's Sunflowers, the actual object displayed in the gallery, stands behind the parade of simulacra, authenticating their value like gold backing paper money. The basis of its significance as a cultural artifact becomes tautological: like the Kardashians, it's famous for being famous, valuable because it's valued.⁵ Whatever it might have meant to anyone in the late nineteenth century is wholly beside the point.

If there was no reason to continue the story beyond 1990, we could pretty much leave the whole thing right here.

(Think of this post like that part in Final Fantasy VI where you have to guide two parties on separate paths through the dungeon and can only advance to the final stage after each group has reached the end of its own route. In other words—we'll come back to this.)

QUESTION #2: Even if E.H. Gombrich doesn't have much to say about the performing arts, don't playwrights, composers, actors, and musicians deserve the name of artist?

Why not? Visual art is made by visual artists. So why can't we say that performing artists make performing art?

...Or do they do performing art? Is there a difference?

Oh, yes. We've come to another esoteric pet topic of mine: reification.

In a passage I've transcribed for this blog at least twice, B.F. Skinner called it a misleading predilection for things. His examples were "poetry" and "pyramidality"—the first an indefinite trait or type of spoken and/or written language, the other a characteristic we identify in pyramidal objects, but which has no independent existence apart from them. Rather than going too deep into the weeds, let's just grant that Roscelin was more or less correct in judging abstract concepts as flatus vocis: mere words, which we use to "nominate" recurrent facets common to any number of real objects and intellectual "constructs" in the same manner that we point to and call out the names of actual things.⁶

The regularity with which we perform a similar verbal trick with regard to events apparently never caused as much philosophical confusion as did (does?) the reification of concepts, but it nevertheless produces some occasionally interesting phenomena.

Imagine that somebody in Boston at 7:01 EST says, "I'm going to see Hamlet." Elsewhere—let's say Seattle—somebody announces at 4:01 PST "I'm going to see Hamlet." Each Shakespeare enthusiast then leaves to visit their local playhouse or outdoor stage and sees a troupe's production of a play called Hamlet.

On the face of it, it's strange that two people who state "I'm going to see [Proper Noun]" go on to witness two completely separate events, occurring thousands of miles apart, involving totally different people.⁷ In effect, this is a bit like saying that two construction crews, employed by the same scummy real estate developer to build two "fast-casual" condos from the same blueprints on opposite sides of town are each busy erecting the same building.

What do we mean when we say "Hamlet"—a text composed by William Shakespeare circa 1600 that has been consistently reproduced in a static form for centuries, or any given occasion where a group of people stand in front of other people and recite that text?

|

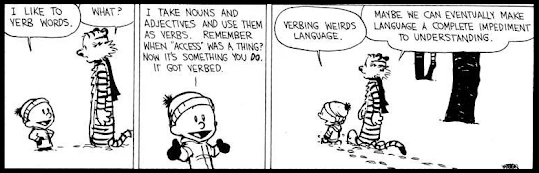

| Bill Watterson's Calvin and Hobbes (January 25, 1993) The strange fact of the matter is that verbing usually accurates language.⁸ |

From his viewpoint as a representative of the civilization in which the Western dramatic tradition originated, Aristotle is inclined to quote the eponymous Danish prince: "the play's the thing." He doesn't consider Electra (ca. 420–14 BCE) or The Trojan Women (415 BCE) to be essentially different literary forms than the Homeric epics. All of them are poetry. Homer writes as a narrator; Sophocles and Euripides "imitate" their characters. All of them intended the words they wrote to be recited before an audience.

Analyzing the elements of tragedy in the Poetics (ca. 335 BCE), Aristotle ranks them in order of importance: Plot, Character, Thought, Diction, Song, and—at the bottom of the list—Spectacle.

The Spectacle has, indeed, an emotional attraction of its own, but, of all the parts, it is the least artistic, and connected least with the art of poetry. For the power of Tragedy, we may be sure, is felt even apart from representation and actors.

|

| Purportedly a photo of an Oedipus Rex performance. The internet's collective intelligence seems unclear on its source. |

Apropos our earlier remarks on the displacement and reproduction of art-objects: the stage play, opera, ballet, etc. might have seemed, to the naïve aesthete of the mid-nineteenth century, immune to the paroxysms that wracked the visual arts community after the invention of photography. The performing arts might have been expected to cling to their aura (some of which was surely lost in the evolution of the secular drama from the passion play) with more tenacity by virtue of their status as an events. That's the reason I've been harping on this: as an object, a text can be reproduced—but an event can't. A given performance of Hamlet can't be transported, put on an auction block, staged in perpetuity in the lobby of a Manhattan office building, etc.

|

| Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) (ooh la la) |

|

| pixelartmaker.com creator ID no. 9664c4 |

|

| Takashi Murakami, Tan Tan Bo (2001) (Superflat.) |

|

| [shibboleth] |

1. I suppose you could also turn over Duchamp's Fountain and piss in it, but a urinal doesn't exactly do what it was designed to if it's not connected to a plumbing system. Besides, the Venn diagram constituting "things people make" and "things you can piss on" is a smooth-edged circle.

2. Cf. Raymond J. Starr, "The Circulation of Literary Texts in the Roman World" (1987)

3. Edward J. Minskoff (of Edward J. Minskoff Equities) purchased Balloon Rabbit (Red) at Christie's in 2013 for $58.4 million.

4. Trevor Fawcett, "Graphic Versus Photographic in the Nineteenth-Century Reproduction" (1986)

5. In general, the cultural capital of painting has seen significant deprecation. If I asked you to name ten famous painters off the top of your head, how many of them would be figures who rose to prominence in the last fifty years? The flight of fine art from areas where it must compete with photography and with more affordable home décor has carried it into territory where only curators, career critics, and the ultra-rich are truly interested in following it.

A painter, sculptor, or mixed media artist—Mr. Koons, for instance—can still have an obscenely lucrative career, but they are the exceptions to the rule. Someone who isn't so well known, who can't expect to sell for millions of dollars a garish sculpture depicting himself fucking his porn star girlfriend, would probably do better designing something for a manufacturing run than selling handpainted canvases, chiseled stone objects, etc.

6. I'm resisting the urge to transcribe or paraphrase page after page of Verbal Behavior (1957) and Relational Frame Theory (2003), which is to say that I admit that this paragraph prompts a lot of wonky questions. For once, I'm trying to stay more or less on topic.

7. This sort of thing was probably less common before the rise of the regional, national, and multinational franchises, and this is why I advocate giving at least a little attention to the philosophy of nominalism.

8. Cf. Jorge Luis Borges, "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" (1940)

9. I'm sure that contemporary urbanites with season passes to their local performing arts center recognize that no two nights on the stage are completely alike, but who cares. I mean—when was the last time you thought much about plays or orchestra concerts?

10. It just occurred to me that A Midsummer Night's Dream might be considered the primogenitor to Mystery Science Theater 3000. Tell your friends! They'll think you're very smart and cool.

11. In spite of appearances, Heraclitus is still correct: no two viewing occasions are the same. The equipment degrades, the viewer ages, the entropy in the universe increases, etc.

12. I balked at including "sprite comics" in the list.

13. Coincidentally, Nick Carr recently summed the matter up and saved me from having to write anything else here:

[Walter] Ong showed that while the “secondary orality” engendered by modern electronic media shares certain important characteristics with preliterate “primary orality,” it is nonetheless a fundamentally different phenomenon. Underlying it is a different state of consciousness. Once technologized, neither speech nor consciousness can be de-technologized.

It might be a fatuous analogy, but compare primary orality to fish and secondary orality to cetaceans: their genetic line's departure from and return to the sea produced an order of animal with as many anatomical and behavioral differences as superficial similarities to fish.

I feel a little called out by those Aunty tropes. But then, I'm always preferring art for my own sake, maybe to signal a shared interest for conversation but not worthiness.

ReplyDelete