This has been something I've meant to do for a long time. The images I collected for a Shade, The Changing Man writeup are in a folder that's almost three years old. There just never seemed to be a good time to go ahead and make it happen. Lately I've gotten it into my head that there are a couple of other underappreciated comic books that I'd like to write about, so I figure I might as well do a little series, starting with Shade.

Shade, The Changing Man is the seminal comic serial of author Peter Milligan, who might be better known for his work on mainstream superhero titles like Detective Comics,* X-Force, X-Men, and Justice League Dark. It launched in 1990 and concluded in 1996 after seventy issues.

*As a matter of fact, it was Milligan who came up with the idea of the bat-demon Barbatos, and he was a co-creator of Azrael, the guy who briefly replaced Bruce Wayne as Batman after the Knightfall storyline.

I can't speak to how popular Shade was in its own time, but it's telling that as recently as 2014, the trade paperback collections only went up to issue #25. (Having been introduced to the series through an impulse purchase of the first volume at a bookstore, I can't tell you how crazy this made me.) I can't remember what year it was that I checked again, but it couldn't have been more than a half a decade ago that I browsed the DC Universe digital catalogue and found that it excluded issues #51–70.

Compared to 1990s Vertigo hits like Sandman, Preacher, and Doom Patrol, Shade, The Changing Man has been mostly forgotten. I won't venture to guess why that might be—its pervasive weirdness and the unremitting flakiness of its protagonist could have something to do with it—but whatever the reason, Shade's status as an eclipsed also-ran is a damned shame. It's easily as good as any of its Vertigo contemporaries, if not better.

Any overview of Shade, The Changing Man can't avoid making reference to two other comic books. One of them is Neil Gaiman's Sandman, which we'll talk about later. The other is, uh, Shade, The Changing Man.

The first comic book called Shade, The Changing Man hit newsstands and spinner racks in 1977. Written and drawn by Steve Ditko (better known for co-creating Spider-Man and Doctor Strange with Stan Lee), Shade, The Changing Man was a sci-fi/fantasy superhero comic about Rac Shade, an alien agent from an extradimensional world called Meta. Framed for treason and accidentally sent to the "Earth-Zone" along with Meta's imprisoned Crime Czars, Shade fights to bring Meta's expatriated malefactors to justice and clear his name with the help of his M-Vest, a device that can project illusions, create protective force shields, negate gravity, and all sorts of other exciting action comic stuff.

In addition to battling Metan gangsters who've set up shop on Earth, Shade fends off his erstwhile fiancée Mellu, who's been sent to assassinate him under orders from his boss and mentor Wizor. ("My love for Shade has turned to...to hatred!" she soliloquizes.) He's up against impossible odds, but Shade is no amateur: being the only Metan who's ever visited the interdimensional Zero-Zone's "Area of Madness" and came out with his sanity intact, he's got something of a reputation among Meta's lawmen and criminal element alike.

And that about exhausts what needs to be said about Steve Ditko's Shade, The Changing Man as far as concerns our purposes here. It's not a bad superhero rag by any means—it's redolent of Jack Kirby's "Fourth World" books, and I can only ever mean that as a compliment—but just as it was gaining momentum, it became a casualty of the DC Implosion of 1978. Issue #8 ends with a teaser and an "on sale" date, and there wasn't an issue #9.

Shade's original run must have had its fans, and writer John Ostrander was evidently among them. He liked Shade enough to have Amanda Waller draft him into Task Force X during Suicide Squad's first (and incontestably best) iteration the late 1980s, and stuck around for a whole twenty issues—a relatively long run for a character in a serial with such a frantically rotating cast. Shade's sudden and unceremonious exit from the book probably had something to do with the planned launch of Milligan's all-new, all-different Shade, The Changing Man six months from then.

The coexistence of Ditko's Rac Shade with Milligan's Rac Shade in the shared Post-Crisis continuity of DC Comics is definitely a problem insofar as they're completely different people, but it only really matters if we give a damn. I'm inclined not to.

Where Milligan's Shade is concerned, Ditko's Shade never existed. Conceptually, the original Shade is merely the new iteration's template, a concept to be reimagined in the context of a bronze-age "prestige" comic serial that deconstructed and reassembled the superhero archetype. (Thanks in no small part to Frank Miller, Alan Moore, and Grant Morrison, this sort of thing was very much in vogue during the late 1980s and early 1990s.)

Milligan's Rac Shade is still an alien from an extradimensional planet called Meta. He still has a fiancée named Mellu and mentor named Wizor (er, Wisor?). He's still equipped with an M-Vest, and has been to the Area of Madness. But this version of the story doesn't cast him as a fugitive: here he's been dispatched to Earth to fight an evil which threatens his world's existence. And he's not socking anyone in the jaw anymore; this Shade is much less a man of action than a man of feeling and imagination.

Straightaway, the new Shade, The Changing Man makes clear that its protagonist isn't a typical superhero. He's far too much of a nebbish to qualify. Just imagine if Peter Parker was a hapless English major instead of a scrappy news photographer; what kind of superhero comic would The Amazing Spider-Man have been?

I guess it would be precisely the sort of self-consciously genre-bending, semi-parodic "postmodern" superhero that DC's Vertigo imprint was made for, and Shade, The Changing Man is a Vertigo comic par excellence.* These books are practically a genre unto themselves. If we wanted to get more specific than that, we could just google "neil gaiman sandman genre" and file it under whatever heading the algorithm offers.

*Historical note: Shade, The Changing Man predates the Vertigo imprint, which was launched in 1993. It was one of several "mature readers" DC titles to get the label slapped on midway through its run. Sandman was another, of course. The rest were Hellblazer, Animal Man, Swamp Thing, and Doom Patrol.

Ah. Sandman is "dark fantasy." So that will be what we call Shade, The Changing Man. Where Sandman goes, Shade follows.

Maybe this is unfair to Milligan, but the synchronicity between his book and Gaiman's would be damned strange if it happened that he wasn't reading Sandman at the time and taking inspiration from it.

Sandman's first issue dropped in January 1989; Shade's came out in July 1990. Neil Gaiman is a Brit with a penchant for Americana, classic literature, and folklore; Peter Milligan is a Brit with a penchant for Americana, classic literature, and folklore. The titular character of Sandman is a person (though really something more than a person) with a lush head of hair and capacious black robes, who straddles the worlds of reality and dreams; the titular character of Shade is a person (though really something more than a person) with a lush head of hair and an ample technicolor overcoat, who straddles the worlds of reality and madness. Sandman began by learning into its horror element, focusing on nightmare monsters and serial killers; Shade began by leaning into its horror element, focusing on nightmare monsters and serial killers. Sandman later branched out into magical realism; Shade later branched out into magical realism. The devil is a prominent character in Sandman and he's not the sort of person we expect him to be; the devil is a prominent character in Shade and he's not the sort of person we expect him to be. Sandman has a memorable storyline involving William Shakespeare; Shade has a memorable storyline involving Ernest Hemingway and James Joyce. Queer characters abound in Sandman and are treated with respect; queer characters abound in Shade and are treated with respect. John Constantine guest stars in a Sandman story; John Constantine guest stars in a Shade story. The names Chris Bachalo, Colleen Doran, and Richard Case appear in Sandman's artistic credits; the names Chris Bachalo, Colleen Doran, and Richard Case appear in Shade's artistic credits.

We could go on. Shade is Morpheus' dysfunctional red-headed younger stepbrother.

And yet—in my old age, and despite having fallen in love with Sandman during my shiny-eyed teenage years, I find I prefer Shade, The Changing Man to Sandman these days. It's not even much of a contest.

I'll admit that one of the reasons I find Shade so interesting is the way it stands as a distorted reflection to Sandman. It does hold up on its own, yes—but it's kind of like, say, SNK's line of 2D fighters, which are impossible to consider in isolation from Capcom's Street Fighter franchise. (I sat for five minutes thinking of an appropriate simile and this was the least obscure one my tired brain could conjure.) Street Fighter II and Sandman were epoch-defining lodestars of their respective media in the early 1990s, and are household names to this day. King of Fighters and Shade, The Changing Man were and are not, and they developed in such ways that can't be accounted for without reference to the titles that cast the shadows in which they grew.

It's difficult not to look back forth between Shade and its more famous and beloved older "brother," and the compulsion to view the book in contrast to Sandman actually works in Shade's favor.

As usual, we've sped too far ahead and need to back up.

Shade, The Changing Man begins not with Rac Shade, but with one Kathy George. Kathy is twenty-three years old, and her life has spiraled out of control.

Three years ago, she took her boyfriend Roger to meet her parents in Louisiana. Roger, as it happens, was black.

They pulled into the driveway at the George household. Kathy opened the front door. A serial killer named Troy Grenzer looked up from the freshly butchered bodies of her parents in the foyer. "I'm not mad," Grezner told her. "I get mad, but I'm not mad."

Grenzer closed in on Kathy with a knife in his hand. Roger lunged at Grenzer, and grappled with him on the front lawn. The police pulled up. The police in Louisiana, remember. They shot Roger in the head and asked Kathy if she was all right.

After some time in the psych ward, Kathy was set loose after the bills piled up and her late parents' money ran out. She drifted and drank, cruising on the money she stole from a wealthy stranger who took her to his hotel room.

Present day: the morning of Grenzer's execution arrives. Kathy stands outside the penitentiary in Texas and watches. The prison is consumed by an explosion of screams, flashing lights, and grotesque mirages. Kathy runs to her car. Troy Grenzer sits in the back seat.

Kathy's day only gets weirder from there. The rest of her life follows suit.

Shade explains to the incredulous Kathy that he's an alien from Meta. His superiors gave him a crash course on American culture, fitted him with the M-Vest, and sent him into the Area of Madness, the dimensional interval between Meta and Earth. From there he used the vest's reality-warping powers to overwrite Troy Grenzer's consciousness with his own as the killer sat in the electric chair. (Grenzer was selected as Shade's host because he was just about to die anyway.)

Shade's mission is to destroy the American Scream, an avatar of the United States' swelling, purulent collective psychosis. The creature has grown to such massive proportions that it threatens to explode, setting off a cosmic blast wave of insanity that will doom not only Earth, but Meta as well.

The first plot twist comes early on: Rac Shade, the person who physically entered the Area wearing the M-Vest, is dead. He's just a corpse floating in the primordial flux between worlds. His boss Wizor betrayed him: his mission to America was intended to be a one-way trip. But because his body died in the Area while wearing the vest—actually, I'm not so clear on this, and Shade, The Changing Man plays fast and loose with the "physics" of its lore—he's permanently plugged into the wellspring of madness and can marshal its powers to change a given situation, fighting insanity with creativity (and what's the difference?) as he encounters the American Scream's ghastly manifestations.

Kathy comes along for the ride. She needs an anchor, and what she gets is a confused alien who's uncontrollably drawn to the grotesque psychic shitstorms erupting across the country. Shade needs an anchor, and what he gets is a profoundly traumatized young woman with nobody else in her life and nowhere to go.

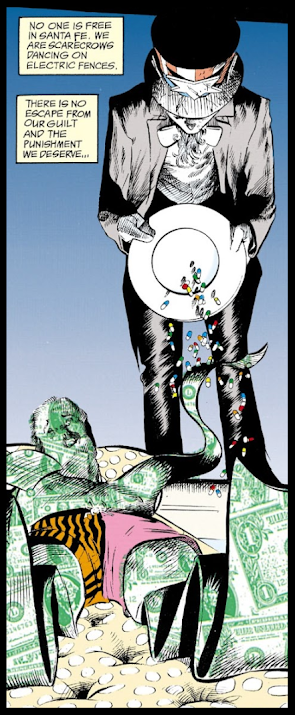

Shade, The Changing Man can't be divided into "chapters" quite as cleanly as Sandman, but the episodic "American Scream" saga is clearly an Act One. Shade and Kathy travel the country, sometimes by car, and sometimes by literally riding the Madness. Shade meets and gives battle to the Kennedy Sphinx (above), a Hollywood director whose madness-infected camera promises to turn all earthly existence into a schizophrenic film, a paranoid Average American turning his neighborhood into Pleasantville by way of Orwell's 1984, a megalomaniacal hippie guru, and other incarnations of American psychosis.

In issue #4, a flashback to Shade's training under Wizor gives us an inkling of where Milligan is coming from:

Replace Shade with author Peter Milligan and switch "Earth" for "America," and this moment verges on the autobiographical. Shade confronts America as a knowledgeable foreigner, as does Milligan.

Remember, Milligan was part of the British Invasion of American comic books during the 1980s. He's an Englishman who grew up in the second half of the twentieth century, when his home country had become a veritable satellite state to a former colony that had grown into a global superpower. It's not hard to suss the real-world metaphor out of the threat the American Scream poses to Meta. When the United States suffers a cultural spasm, the rest of the "free world" twitches with it.

People living outside America's borders might shake their heads at our lunacy and resent our government throwing its economic and military weight around. And yet, they're happy enough to be the captive audience of our culture industry. Thom Yorke of Radiohead sings about wanting to be Jim Morrison. When Star Wars arrived in the United Kingdom in December 1977, scalpers were buying tickets for £2.20 and having no trouble selling them for £30.00. And, of course, the aforementioned British Invasion wouldn't have happened if Alan Moore, Garth Ennis, Grant Morrison, Warren Ellis, et al. hadn't devoured American comic books growing up.

It's not uncommon for comics of the British Invasion to evince a more intense interest in the United States' anatomy and psychology than their American contemporaries. After all, their authors were writing from the vantage point of the propinquant foreigner. To them, America and its culture weren't an invisible ambiance to be taken for granted; the United States was an uncanny other. Neil Gaiman explored it as a curious, observant tourist. Garth Ennis embraced it. Alan Moore flipped it the bird.

With Shade's "American Scream" arc, Milligan says the quiet part out loud. In one way or another, he and his peers availed themselves of their deals with a major American comics publisher to conscientiously react to the inescapable cultural maelstrom called America, which had swept them all up from afar pretty much as soon as they were put in their swaddling clothes. There's no beating around the bush with the American Scream: Milligan writes a comic book in which the United States is a haunted house populated by sui generis American ghosts that must be exorcised before they spill out and drive all reality insane.

This is all very interesting, but it's over by issue #18. After discovering the treacherous secret of the American Scream, Shade puts the monster down for good. Given how the book has progressed up until this point, you'd expect that to be all. Shade accomplished what he set out to do. The plot met the specified condition of its resolution. What's left but a bittersweet little epilogue and a little word box that reads Fin?

But Shade, The Changing Man continues for another fifty-two issues. How can it do that if it's been deprived of the conflict that fired its engines?

At this point, we need to introduce Lenora "Lenny" Shapiro.

Kathy meets Lenny in New York while Shade is trapped in the psychic dream-fortress of a 1960s San Francisco commune, and is shortly tagging along with Shade and Kathy on their weird-ass odyssey across these United States of Consciousness.

On the face of it, Lenny seems like another barely-disguised imprint of Sandman upon Shade. One of Sandman's most beloved characters was Death, the witty, charming, and wise goth girl with frizzy hair. And—surprise!—Lenny is a witty, charming, and wise goth girl with frizzy hair.

But that does a disservice to Lenny, since the areas of overlap between her and Death of the Endless are largely superficial.

Lenny isn't really "goth" so much as "Manhattan art scenester." She plays at poverty, but comes from a family that's much better off than just well-to-do. She's excellently versed in cinema and modern art; she has the sangfroid of an Andy Warhol and the brash, insouciant humor of a woman who hangs out with drag queens (and is able to keep up with them). We don't know any of Lenny's friends—they're like so many of Ginsberg's angelheaded hipsters, entering and disappearing from the pages as allusions to and anecdotes of New York's eccentric humanity. We'd be justified in calling "Lenny" quirky; what other word is there for somebody who takes up robbing cabbies at gunpoint because she needed a hobby after ruling out suicide?

There's a digressional chapter in Herman Melville's The Confidence Man about "originals" in fiction, which warrants a block quote with regard to Lenny.

As for original characters in fiction, a grateful reader will, on meeting with one, keep the anniversary of that day. True, we sometimes hear of an author who, at one creation, produces some two or three score such characters; it may be possible. But they can hardly be original in the sense that Hamlet is, or Don Quixote, or Milton’s Satan. That is to say, they are not, in a thorough sense, original at all. They are novel, or singular, or striking, or captivating, or all four at once.

More likely, they are what are called odd characters; but for that, are no more original, than what is called an odd genius, in his way, is. But, if original, whence came they? Or where did the novelist pick them up?

Where does any novelist pick up any character? For the most part, in town, to be sure. Every great town is a kind of man-show, where the novelist goes for his stock, just as the agriculturist goes to the cattle——show for his. But in the one fair, new species of quadrupeds are hardly more rare, than in the other are new species of characters——that is, original ones. Their rarity may still the more appear from this, that, while characters, merely singular, imply but singular forms so to speak, original ones, truly so, imply original instincts....

For much the same reason that there is but one planet to one orbit, so can there be but one such original character to one work of invention. Two would conflict to chaos. In this view, to say that there are more than one to a book, is good presumption there is none at all. But for new, singular, striking, odd, eccentric, and all sorts of entertaining and instructive characters, a good fiction may be full of them. To produce such characters, an author, beside other things, must have seen much, and seen through much: to produce but one original character, he must have had much luck.

I won't go so far as to say Lenny Shapiro deserves to join Don Quixote and Hamlet at the empyrean heights of Originals in fiction—but she's certainly eligible for consideration as one, especially in the sphere of comic books. I can't say that I've read every comic serial published prior to her introduction in Shade, The Changing Man #8 (February 1991) and can't assert out that she's definitely and qualitatively unlike any other character to appear before her, but she's nothing if not "novel," "singular," "striking," and "captivating." Whenever I happen to idly remember Shade, The Changing Man, she's the first character who comes to mind.

Shade is, for most of his book's run, Hamlet with superpowers. We've got him figured out. And Kathy instantiates the familiar archetype of the paramour, the damsel in distress, the gentle companion who keeps the male hero grounded. But Lenny is harder to pin down.

The raw material for the character mustn't have been hard to find. Snarky trustafarian art chicks who're penetratingly intelligent and dazzlingly superficial in equal measure are a dime a dozen in the metropolitan human show. I've met people like Lenny, and fell in love with at least one or two of them in my adolescence. And yet I can't imagine extrapolating a Lenny from any of them, nor can I imagine Milligan concocting a Lenny without having met them.

Lenny is eminently transparent in her aggressive and unapologetic quirkiness, but it gradually becomes clear that we never know her as well as we presume to. Whenever we suppose we have her mapped out, she surprises us—but somehow we're not surprised at being surprised. We know her and we don't know her. She's fake and she's real. She's invincible and she's vulnerable. And none of this is inconsistent within the locus of what she is.

Even if she doesn't meet the strict criteria of a True Original, Lenny resists encapsulation, and that's a feat in itself for a character in fiction. I'm tempted to say she's Milligan's greatest accomplishment as an author.

The loose arc following the American Scream runs from issue #19 to issue #32; we could provisionally call it the "Agent Stringer" saga. It's got a road trip and time travel. It's got mystery. Shade's fiancée Mellu appears. There's sex, there's betrayal, there's the splitting of selves and the jumping of bodies. Shade gets killed twice. The first time he gets better—more or less. The second time, however, it sticks.

For about six months.

Kathy and Lenny are taking a bath together one afternoon when Lenny's dead boyfriend Roger floats up out of the suds. (It seems Kathy has somehow absorbed a trace of Shade's madness powers.) Instead of complimenting Katy on her new "I've moved on with my life" hairdo, he tells her that Shade will soon be reborn. The angels are going to plop his consciousness into a comatose man in a mental institution, and she needs to be there to draw him out.

Yes, angels. Now Shade, The Changing Man has angels. But like the American Scream, they originate from the Area. Shade manifests them, and they manifest Shade. Don't expect it to make sense; it's all madness. And why not? Once we leave the safety of politics and physics, any questions we have about the world inexorably lead us to places where reason breaks down.

After the events of issue #50, Shade desperately wants to die, but can't. The last surviving angel explains that he's simply too guilty to die. Call it a plot contrivance, but Shade has already established the capriciousness of the Area and its metaphysics.

Having alienated himself from the rest of the regular cast, Shade bums around New York for a while, and eventually creates a lavish, infinite "apartment" for himself under the Manhattan sidewalk. He settles accounts with old enemies, callously fucks with people, drinks, does drugs, and experiments with existing as a library book, a dance floor, a rose bush—all to cut himself off from a life he's sick of living.

But life doesn't give us a choice but to live it. Weirdness keeps finding Shade (or Shade keeps inventing weirdness), and he has to deal with it—he and the friends with whom he's reunited, along with the new members of his entourage, who all stand by him in spite of how frequently his problems spill over into their laps.

He also gets a new hairstyle, which Milligan introduces with a full-page authorial missive at the beginning of issue #51. Shade's third and penultimate phase can only be called the book's Mod Era.

If you've read Sandman, you won't have a hard time coming up with an answer if I asked you to identify Morpheus' singular defining quality. Sure, he's dark, moody, and more than a little callous. Yes, he's dreamy. But more fundamentally, he is a person (or something like one) who obstinately resists change. "Set in his ways" doesn't do justice to his stubbornness. One suspects he'd have had a better chance of slipping the noose during his series' climax if he could have brought himself to be more adaptable.

"We do what we do, because of who we are," Morpheus soliloquizes before heading off to his last appointment with his sister. "If we did otherwise, we would not be ourselves."Morpheus' tragedy is that he can't change who he is. Shade's tragedy is that he can't change what he's done.

By the time Shade, The Changing Man enters its Mod era, its titular character has long since ceased to be the apprehensive poet with reality-altering powers he's still chary of using. Having mastered the functions of the M-Vest (which have become such an integral part of him that the vest itself is seldom mentioned anymore), Shade is for all intents and purposes a god. He's capable of doing anything he can imagine, impossible to kill, and is lately more inclined to behave as a trickster than a hero.

And then he loses his heart—literally and figuratively. He's a lot happier for it.

I haven't been able to find any direct sources for the claim that Milligan planned to end the book at issue #50 and had to be pressured into continuing the series—but if that's true, it certainly provides material for conjecture as to why he decided to turn his titular character into a shitty little sociopath. One doesn't find very many detailed retrospective articles or venues for discussion about Shade, The Changing Man, but the prevailing opinion seems to be that the series loses its verve after #50.

It's hard to dispute that Shade doesn't change for the better during its Mod era (although the "Impossible Photograph" story in issue #65 goes a long way toward raising the average). The book rather loses its direction and grows convoluted even by its own standards, but I suspect readers might have been willing to forgive its meandering weirdness (or weird meandering) if Milligan hadn't turned his main character into someone they'd have really enjoyed seeing flayed alive.

It was a bold choice, that's for sure, and perhaps not one made by somebody who wished to ensure the longevity of the serial he was writing. But, man—the "Nasty Infections" storyline left an indelible resin in my brain, and the series would have been incomplete without it.

I've personally known people who have gone crazy in one way or another. Most were charismatic, brilliant, talented individuals whose friends and lovers felt privileged to be close to. When they became manic and/or depressive, quit their jobs and disappeared for months, or got hooked on bad drugs, I've usually been happy not to be situated in their inner orbits. The closer somebody was to them, the more liable they were to get burned.

When we were introduced to Shade as a poet-turned-operative, his Madness powers were sometimes treated as a metaphor for the act of artistic creation. "Be a poet of insanity," Wizor advised him before he embarked for Earth via the Area of Madness. "Create free verse with reality...Forge whatever change is needed on the smithy of your soul."

Shade insinuates the popular truism that madness is an indispensable ingredient of the of genius that changes the world. A corollary to this is that the brilliant artist who creates something of transcendent, lasting value is often a horrible asshole who wreaks misery on the people closest to him, even as he makes life better for everyone else. In his capacity as a poet of insanity who's prevented an apocalypse, solved crimes, and slain monsters, Shade has brought a lot of collateral damage down upon his friends. Through it all, they've always cared enough about him to give him the benefit of the doubt and forgive him.

Now, at the very apex of his powers, Shade turns into a dark-triad demigod who blithely lets his friends get killed by his own insane bullshit. He's too wrapped up in himself to feel very bad about it, and far too slippery and strong for anyone to hold him accountable. Rereading these issues, I feel like I have a glimmer of insight into the rage and anguish Sophia Tolstoy, Jill Faulkner, and Edie Sedgwick must have suffered by dint of their proximity to men of genius.

Nothing is permanent in mainstream comic books. Unpopular stories and their aftereffects are routinely reversed through retcons, convenient plot contrivances, or by simply waiting a while and then pretending none of it happened.

It might seem that Milligan is up to something of the sort when issue #68 begins with Shade showing off the time machine he built. He's accepted his heart back into himself (we might say this is a magical realist metaphor for getting therapy, taking meds, going clean, etc. after hitting rock bottom), and wants to make amends for what he's done by undoing it. All of it.

He gathers up the friends he's wronged and explains his plan to go back in time and prevent his arrival on Earth from ever happening. Since doing so will effectively erase them all from existence, he invites his friends to come with him, where they'll be shielded from alterations to their histories. After he does what he needs to do, he'll drop them back off in the changed present. (However they deal with their other present-day selves moving about in the Shade-less timeline will be up to them.)

We could read this as the act of an author sent into a bit of a panic by the lousy reception of his serial's previous chapter. The fact that Shade has reassumed the familiar manners and appearance of his original incarnation recommends itself to suspicions that Milligan lost his nerve and is hurrying to please readers by giving them back the most likable version of his book's protagonist. This sort of thing usually backfires, of course: even if "Nasty Infections" left us angry and nauseous, how can we feel anything but contempt for an author who lets himself be bullied by his audience?

I think it's more probable that Milligan was up against an editor who told him was book was about to be cancelled, and he needed to use the last three or four issues of Shade, The Changing Man to not only wrap things up, but to make people like Shade again—even if that meant backpedaling on three years of character development.

I'm just making this up; maybe or probably this scenario isn't anything like what actually occasioned the writing of Shade's final issues. Perhaps Milligan simply got tired of the book after six years and was in a hurry to end it.

But if we prefer to imagine that Milligan's decision to end Shade, The Changing Man by rebooting the timeline and cancelling out nearly everything that happened from issues #1 through #67 wasn't his first choice, we have to admit he found a way to own it. Maybe it's not the most satisfying ending anyone could have envisioned for the book, but it remains true to what came before.

Shade murders Wizor in the past, preventing his younger self from ever getting conscripted by his perfidious mentor. He destroys the American Scream before it can manifest. He visits Louisiana and stops Grenzer from killing Kathy's parents and her college boyfriend Roger. At Lenny's insistence, he lets her off the ride to change a couple of events in her own past. By the time they return to the present day, Shade's madness powers are apparently all used up.

What Lenny finds when she returns to the present is the first harrowing indicator that Milligan never intended to wave a magic wand and set everything right. Without going into detail, Lenny trades an ineffaceable scar for an open wound, and there's nothing else Shade can do for her.

Shade doesn't have it much better. Deprived of his madness powers, he's a nobody. He's got no past, no connections, no job, no money, no mobility. His plan, his desire, his every waking thought, is to reunite with Kathy—or the new and current version of Kathy, one who never saw her parents sliced to pieces by a serial killer, witnessed her boyfriend getting shot in the head by a cop, ended up in a psych ward, became an alcoholic, or traveled America helping an alien agent fight an incarnation of national insanity. (The old timeline's Kathy didn't board Shade's time machine.)

We don't know how Kathy's life turned out without Shade. Milligan doesn't allow us to see her. The final issue has Shade working as a dishwasher to keep a roof over his head as he tries to figure out where Kathy ended up (this was in the late 1990s, remember; he couldn't just google her name) and save up enough money to travel to wherever she is.

Though he intended at the onset to turn himself around and be a better person in the new reality he made, he eventually opts for a bloody expedient in getting to Kathy. Even for a person who can travel through time and scrub his past mistakes from the cosmic record, there's no such thing as a clean start. (What was that line from Macbeth? "I am in blood stepped in so far, that, should I wade no more, returning were as tedious as go o'er...")

However it might look to the jaded comic book reader accustomed to evasive midstream rewrites like "Jean was never really dead" and "Cyclops is alive again because time travel," Shade's last story is anything but a cop-out. Nothing is dialed back.

Five years after watching a redheaded stranger saving her parents and boyfriend's lives, Kathy lives in a farmhouse in rural Montana. (Does she live there alone? Is she still with Roger, or has she found somebody else? Are there any kids? We don't know.) Shade shows up at her doorstep with an unbelievable story and a copy of the other Kathy's handwritten diary detailing her adventures with him and Lenny. Shade, The Changing Man ends with her inviting him inside, apparently willing to hear him out.

When Shade and Lenny discuss the ethics of changing the past, Shade dismisses the question of whether or not it's right. He's seen and done too much to believe that "right" exists.

"What's possible," he says, "that's all there is."

That's as happy an ending as Shade can get: the possibility of things working out. For the last five years he's been the mad alchemist of possibility, sublimating the impossible into the actual. Now his charms are o'erthrown, what strength he has's his own...

Oh, god. Sandman ended with The Tempest. And now here I am conjuring it for a description of Shade's last issue. I don't think we can accuse Milligan of aping Gaiman here, but it's eerie that there should be such an obvious conceptual thread connecting Shade, The Changing Man #70 to Sandman #75 via The Tempest.

To wrap up the metaphor, Shade at last finds himself in the uncertain but hopeful position of Prospero at the moment the old magician delivers the play's closing soliloquy. Though we've come to know Shade as the ultimate mover of his world, its caller of storms and tamer of spirits, whatever happens on the unwritten pages that follow is no longer up to him.

The stories of Sandman and Shade both end on a note of anticipation, but their moods couldn't be more different. For all Gaiman's aptitude for gruesome horror scenes and graveyard humor, there's something fundamentally smarmy about his work that becomes a mite cloying once you notice it in the very ligature of his compositions. That's not to say I dislike his comics, or would dare say he hasn't accomplished incredible things in his career, but Sandman, Whatever Happened to the Caped Crusader?, Marvel 1602, etc. all leave me with a kind of saccharine, stevia-like aftertaste on my palate. Gaiman just can't help being cute. Of course Sandman's final act concludes with the reader waking from a strange and wonderful dream before he or she is ready for it to end.

Milligan doesn't have that problem. In fact he rather errs on the side of leaving out the sweetener and letting the bitterness through. Shade, The Changing Man doesn't end like a passing dream. This is a book that takes you places, and leaves deep and lasting gashes as souvenirs of the trip.

We ought to wrap things up with a glance at the afterlife of Shade, The Changing Man.

In 2016, DC launched the title Shade, The Changing Girl under its Young Animal Imprint. It concluded in 2017 after twelve issues, and was followed by the six-issue Shade, The Changing Woman in 2018. Written by one Cecil Castellucci, the books follow the story of a young woman from Meta named Loma. Inspired by her idol, the poet and adventurer Rac Shade, Loma adopts his last name, steals an M-Vest, and departs for Earth.

I'll admit I haven't done much more than skim these books, but I suppose they're true to Milligan's series in running with one of its analogies, to which they add a "never meet your heroes" theme. What I recall of the book makes me think of any number of stories of a young female grad student absorbed into a toxic relationship with a male superstar writer she'd always admired. Loma discovers that Shade isn't who she thought he was—Castellucci's Shade is like Milligan's during the character's heartless, sociopathic mod phase, only now he's been stewing in his own psychotic narcissism for god knows how many years—and is finally compelled to confront, fight, and defeat her idol.

I remember being irritated by what seemed like character assassination on Castellucci's part. Even though Shade is technically at DC Comics' disposal and doesn't belong to Milligan, I felt it was crass for another writer to arrogate to himself the license to decide the trajectory of Shade's life after the end of Milligan's series. Frankly, I feel the same way about how later writers have handled Madrox, Guido, Rahne, et. al after the conclusion of Peter David's X-Factor run—by that point those characters belonged to him as much as Don Quixote belonged to Cervantes—but them's comic books.

But I'd missed something: I'd opened up Castellucci's books before peering into Milligan's fifty-issue run on Hellblazer, which began in 2008.

While writing Shade, The Changing Man, Milligan had John Constantine guest star in a story during the book's "Hotel Shade" phase. Fifteen years later, when he was at the helm of Hellblazer during the long-running Vertigo title's final stretch, he had Shade appear for a few issues to help Constantine.

Sort of. Shade isn't interested in helping anyone anymore.

The above panels are from Shade, The Changing Man #44. Milligan retcons them during a flashback in Hellblazer #269, inserting a fourth panel between the second and third ones here. Turns out Kathy did did smooch Constantine.

Still—I hope we never see Lenny again. Somebody in Shade's world deserved to come out the better for having known him.

NEXT: A Comedy of Trauma

No mention of Agent Rohug at all?

ReplyDeleteSince I cannot possibly leave well enough alone I hope that DC takes another stab at Rac Shade or at the very least comes out with some Shade merchandise. I've been wanting a Shade coat since the 90's.

ReplyDelete