Picking up from where we left off...

#5: MESSIAH WAR (2009)

Titles involved: Cable, X-Force

In brief: Bishop travels through time and destroys the world to kill Hope, the mutant messiah. Cable and X-Force fight Stryfe like it's 1991. Deadpool boosts sales.

Well, let me get back to you on that. Point is, I knew that whatever Wolverine in a black "stealth" costume was supposed to be, it definitely wasn't X-Force. Marvel was just cynically attaching an old title to a new book to entice old geeks who've let nostalgia make them smooth-brained.¹

Then around 2009 I caught up on the X-Men lore by reading the trade paperbacks during my lunch breaks. After eating my words regarding the Scott/Emma pairing, I had my hasty rejection of Craig Kyle and Chris Yost's X-Force for dessert. Though I've seen it getting mixed reviews in those corners of the internet that collect opinions about superhero comics the way a swimming pool filter amasses dead insects, I am an enthusiastic fan. And in any case, its influence is undeniable: I'll venture a bet that at this point, the only people who associate the X-Force title with Cable and Cannonball instead of Wolverine and Archangel are old men who found better things to do with their time and money than follow superhero comics at least two decades ago.

Despite redefining the title, Kyle and Yost rather seem to have gone out of their way to make the book's first crossover event a petri dish for classic X-Force callbacks. The other book featured in Messiah War was the relaunched Cable series; one the crossover's two main antagonists is Stryfe; and Deadpool (who, you'll remember, first appeared in Rob Liefeld's X-Force while it was still technically The New Mutants) puts in an appearance pretty much just for the hell of it.

Actually, scratch that: Kyle and Yost had a perfectly good reason for bringing in Deadpool. Yeah, it's hilarious that he got trapped in the basement of a collapsed building and his healing factor kept him alive and peppy for almost a millennium, and that's the point. Messiah war might be the darkest story on this list. Without Deadpool's comic relief, it would be too grim and too joyless to be much of a good read.

What makes X-Men comics so much fun to write about (and even more fun to write, I'd hope) is providing exposition by matter-of-factly typing "Cable and Hope's time machine only allows them to jump forward, Bishop's time machine lets him travel into the past and future, and X-Force's jury-rigged devices can only bring them to Cable's chronological 'location' and give them twenty-four hours to accomplish their mission and warp back to the present before the stress of temporal displacement starts killing them."

Bishop, still convinced that killing Hope will change history so he doesn't have to grow up in a concentration camp and watch his parents die, abandons chasing Cable and Hope farther and farther into the future and takes a more strategic approach. Traveling between the twenty-third and twenty-ninth centuries, he systematically renders the Earth uninhabitable to restrict his quarry's range, and then allies himself with Stryfe, who possesses technology that can lock down teleportation and time travel. Cable and Hope find themselves trapped in a thirtieth-century hellscape where most of humanity has died out, and the remnants are completely under Stryfe's control. Now X-Force shows up on a black-ops mission to assassinate Bishop, and must also disable Stryfe's time trap unless they want to perish at the bottom of the toilet bowl into which Bishop turned the future.

When I was trying to figure out how to arrange Utopia and Messiah War in the #6 and #5 slots, the deciding factor was Bishop. There's a lot of good, crunchy, comic-book fun in Messiah War—X-Force ultraviolence, Cable being a papa bear to a nine-year-old Hope (who's still wholly endearing and not yet Nate Grey 2.0), Stryfe reprising the villainous A-game he brought to the climax of the X-Cutioner's Song, and Deadpool being Deadpool. But the Passion of Lucas Bishop, carried over from his ongoing role as the bête noire of Duane Swierczynski's Cable series, delivers the pathos.

Without getting into whether abruptly turning Bishop from a principled military cop to murderous fanatic was a good idea to begin with, Swierczynski does a fantastic job committing to it. He's said in interviews that he doesn't think of Bishop as a villain, but as someone who's willing to sacrifice everything to do what he believes is right. Bishop's absolute certainty that killing Hope will reboot his timeline and make the world a better place (and let's give the experienced time traveler the benefit of the doubt and say he knows his abstruse temporal cryptophysics) gives him license to commit whatever atrocities might be necessary to succeed in his objective, because Hope's death will cancel them all out. "It's not real," he keeps telling himself in this nightmare future he's created. "None of this is real."

And he'll be right—as soon as he puts a bullet in a little girl's brain. In the warped arithmetic of the Messiah War, if Bishop kills Hope, he's innocent. If he doesn't kill her, everything he's done during the attempt is on his conscience. He's got no choice but to see his mission through to the end, and the moments when he lets himself feel how much he hates it almost make you want to cheer for him. Then you see him leveling a barrel at Hope, and you wish somebody would put him out of his misery. It would be best for everyone, including Bishop. He isn't a villain, but a tragic hero in the Classical mold: I'm not certain whether my feelings about him ultimately land on admiration for his determination and strength, revulsion for how low he's sunk, or pity for the mutilation and inexorable misery he suffers. For a superhero crossover story involving two books derived from an early-nineties Rob Liefeld rag, that's quite an achievement and a very pleasant (if harrowing) surprise.

Most important development: All of us had a good time.

Actually, nothing of much lasting consequence happens in Messiah War. By the end of the story, the members of X-Force are literally back where they started. Bishop's still running amok. It's business as usual for Cable and Hope. Stryfe may or may not be done for (spoiler: he isn't), but we already assumed he was dead before the arc began. The timeline Bishop created by systematically despoiling the environment gets shuffled into the multiversal stack as soon as Swierczynski's Cable book ends, and at this point it matters about as much as to the mainstream continuity as the Marvel 2099 AD reality.

I'm going to say Messiah War's lasting impact was renewing Apocalypse's villain cred. Almost from the beginning, En Sabah Nur's shtick has consisted of being the first mutant, the strongest mutant, an implacable immortal menace, a nemesis without peer, etc., but it became harder and harder to take him seriously every time he got his teeth kicked in. Messiah War slyly acknowledges the sorry state in which we find Apocalypse (his monologuing about how much he'd let himself go is practically delivered with a wink to the reader), and gives him an omega-level foe he can curbstomp without necessitating the cancellation of anyone's ongoing book.

It seems to work: Apocalypse doesn't appear much throughout the 2010s (well, at least not as the En Sabah Nur we know), but the dread with which people speak of him suggests they're not thinking about all those times the X-Men beat him without sustaining so much as a single casualty, and neither should we.

Favorite moments: After getting cut up by Wolverine, a seriously ticked-off Stryfe telekinetically forces him to plunge his claws into his eye sockets. I refuse to believe this isn't a callback to the Fabian Nicieza days, when Cable and Stryfe would utter the expletive "stab his/your eyes," the thirty-ninth century-equivalent of "go fuck him-/yourself." Stryfe is literally adding insult to injury, and I can't help but chuckle (in spite of the horrific violence).

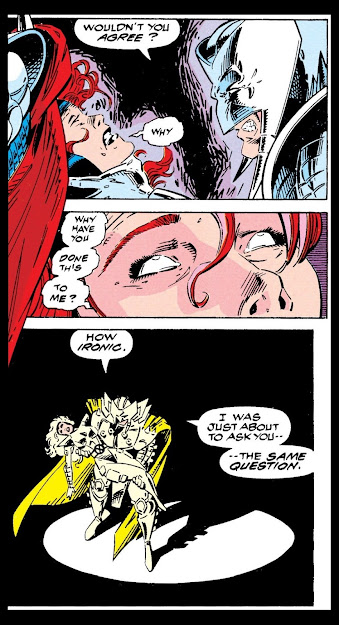

Also: the scene where Hope first sees Stryfe without his mask is adorable (in spite of things getting real ominous in short order).

#4: INFERNO (1988–9)

Titles involved: New Mutants, Uncanny X-Men, X-Factor, X-Terminators

In brief: Goblin baby-snatchers. Ambitious demons with viruses that make them into robots. A portal connecting Manhattan to a nether dimension. A clone with an infernal contract and an axe to grind. A megalomaniacal eugenicist with superpowers. A young woman must choose whether to save the world or save her soul. A boy who can turn his wheelchair into anything he wants. The Empire State Building. Then the mansion blows up. How does it all fit together? Good god, I'm still trying to figure it out.

The long story: Okay. Seriously, let's try to summarize this thing. The demon N'astirh, ostensibly working under the demon S'ym (who's usurped control of Limbo from Magik), sends his goblin henchman into the world to kidnap ten mutant infants to be used as components in an eldritch spell. The young mutants taken into X-Factor's care during that team's "mutant solutions" period (plus the new character Wiz Kid, whom we'll talk more about in a sec) attempt to rescue the abducted infants as the gnarly, totally tubular new teen team, the X-Terminators. Once cast, N'astrih's spell will hijack Magik's next teleportation disc, opening a giant portal to Limbo in the Manhattan sky. The ritual succeeds; the gate opens, and New York becomes a demonic free-for-all. The X-Terminators and the New Mutants manage to close it off, but the damage is already done. They devote their efforts to rescuing Magik from S'ym, N'astrih, and her own dark side.

Whew. Okay.

Meanwhile, N'astrih also has an arrangement with Madelyne Pryor to retrieve her missing son Nathan and help get her revenge against the Marauders.² When N'astrih senses she's becoming too powerful and willful to control, he leads Madelyne into the clutches of Mr. Sinister. The revelation that she's nothing but a clone of Jean Grey makes her even more desperate, angry, and willing to help N'astrih conquer the world purely out of spite. The X-Men and X-Factor—already distrustful of each other, and increasingly corrupted by the ambient magics of Limbo—have to stop trying to kill each other long enough to take N'astrih out of commission and prevent Madelyne from sacrificing Nathan to complete Limbo's merger with Earth. Then they have to bring the fight to Mr. Sinister himself to pay him back for dicking around with everybody's lives.

Okay. I think that's it. Well, there's also the Inferno-adjacent stories in Excalibur, Power Pack, Daredevil, etc., but the hell with them.

Obviously there's a lot going on in Inferno, but Chris Claremont and Louise Simonson do an admirable job of coordinating the chaos. The entire thing can be bracketed into the "Magik" and "Maddie" arcs, the former of which plays out in Simonson's X-Terminators and New Mutants, while the latter goes down in Claremont's Uncanny X-Men and Simonson's X-Factor. The characteristic New Mutants wackiness is boxed into the "Magik" bloc, while the Claremont-style soap operatics reach their latest crescendo in the "Maddie" plot.

The "Magik" thread begins, without Illyana Rasputin herself, in the pages of the X-Terminators miniseries. Reading X-Terminators again, I don't believe I hate it quite as much as I thought. It's sort of like Justice League Dark by way of Archie Comics (and of course I mean the zero-calorie vanilla "classic" Riverdale stuff), and has its share of charming moments as a dumb book about teenagers sneaking out of their boarding school and getting into trouble. I'll give Simonson credit for arriving at a precarious equilibrium between humor (one of N'astrih's goblins misunderstands what a spellchecker does, which becomes a major plot point) and the macabre (a pack of demons rips a cop to pieces and devours him in front of children), but she deserves a very stern wag of the finger for not only introducing Wiz Kid into the world, but making him the miniseries' central character. Wiz Kid is, uh, an orphaned Japanese paraplegic with dyslexia who only eats organic whole foods and has the mutant power to turn any piece of artifice or technology into whatever gadget he wants through the magic of the comic book medium. He's entitled to a slot on any "worst X-Men of all time" list, and Simonson wisely sent him to the cornfield before rolling the rest of the X-Terminators into the New Mutants.

The chapters of Inferno running through The New Mutants picks up from where X-Terminators left off, and are about the apotheosis and end of Illyana Rasputin. Her traumatic childhood experiences in Limbo and her sometimes reluctant reign as its Sorceress Supreme were never far from the fore of the New Mutants' plot, and here it finally comes to a head. The details of her inescapable trajectory towards tragedy in its final hours are surprisingly touching: it's hard not to feel really horrible for her as she's repulsed by her own image and ashamed to be seen by her beloved brother after the last shreds of her humanity slip away. Her epilogue—getting rebooted as six-year-old who doesn't have to spend her formative years getting abused by demons in a hellish alternate dimension and can hope to live a full and happy life—was probably more heartening to anyone who read Inferno before knowing that Illyana Rasputin 2.0 dies from an engineered plague just a few years later. Well, them's comic books.

When the original team reunites for the New Mutants' third volume in 2009, it can be frustrating to watch Sam and Roberto going to such lengths to defend a shady, soulless copy of their old friend. Revisiting Inferno reminds you why they're so eager to make themselves see the good in the woman claiming to be Magik, in spite of the multitude of indicators that she's not on the level at all.

I read Inferno's "Maddie" thread as the making of lemonade from editorially-mandated citrus. After all was said and done, Claremont intended for Jean Grey to stay dead after the Dark Phoenix Saga. When he introduced Madelyne Pryor a few years later, it was as a red herring. She looked too much like the deceased Jean not to be an amnesiac or disguised Marvel Girl, but the real twist was the absence of a twist: Madelyne, as it turned out, actually was just an ordinary woman. Then X-Factor launched in 1986. Its premise (get the original five X-Men back together) required that Jean Grey be alive somehow, and Cyclops had to walk out on his wife and infant son to gallivant around with his high-school buddies and get reacquainted with his old sweetheart. No matter how you qualify or cushion it, Scott has to come out looking like a scumbag. Unless...

...Unless the writers implement a retcon wherein his wife Madelyne was a shadowy clone of Jean all along, and Scott committed some of his less noble actions under the remote influence of the mad geneticist who grew his wife in a vat and experimented on him when he was a child. Brilliant!

N'astrih might be Inferno's prime mover, and Mr. Sinister often receives retroactive top billing by virtue of the prestige he accrued later on, but the arc's best villain is without a doubt Madelyne Pryor (AKA the Goblin Queen—an unfortunate sobriquet if ever there was one). For all her unhinged vindictiveness, it's hard not to sympathize with Maddie. It'd be bad enough to see your husband leaving you and the child he gave you to canoodle with the ex-girlfriend of whom you always reminded him, but to discover, on top of that, that you're an artificial person given life for the sole purpose of reminding him of his ex—yeah, I might want to destroy the world, too.

As a contender, Madelyne is no slouch: the final showdown with Sinister during the story's final act seems a little redundant after the X-Men's protracted struggle against Her Goblin Majesty. She's got all of Jean's powers, she wields black magic, and she's willing to exploit her former husband and friends' emotions while using her own baby as a shield. And you still can't help rooting for her, at least a little, in the darkest cockles of your heart.

Also, as an admirer of Zeb Wells' run on the third volume of New Mutants, I'd be remiss not to mention that the infants N'astrih captures and uses to open the Limbo portal eventually come back as "The Babies," aged to adulthood in Limbo, indoctrinated by a rogue Marines squad, and nastier than anything.³

Favorite moments: It's a testament to how much Mad Magazine I've read over the years that my first reaction to this panel in X-Terminators was "...is that supposed to be Bill Gaines?" Why, yes it is—and until a quick google search, I hadn't known he also created Tales from the Crypt.

Second: the scenes of demon-possessed objects and people running amok in Manhattan remind me of The Real Ghostbusters, and I do mean that as praise.

#3: SECOND COMING (2010)

Titles involved: New Mutants, Uncanny X-Men, X-Force, X-Men Legacy

|

Though they suffer casualties in the process, the X-Men succeed in spiriting Hope to Utopia. Bastion switches to Plan B: encasing Utopia and a swath of the San Francisco Bay Area in an impenetrable energy barrier, opening a portal to a future timeline on the Golden Gate Bridge, and sending in the Nimrods. The X-Men very quickly grow nostalgic for Plan A.

For the reader who has a life who's unfamiliar with X-Men lore: the Nimrod is an advanced hunter-killer robot from the future, developed by a paranoid contingent of Homo sapiens who anticipates joining Homo neanderthalensis in the hereafter if Homo superior is permitted to survive. In Hickman's House of X/Powers of X, analysis of the timelines from Moira's past lives deduces that the development of the Nimrod is the turning point, the moment where Homo superior slides toward extinction. Think of the Sentinel in Marvel Vs. Capcom 2 as opposed to the ones in the X-Men beat 'em up arcade game: that's the difference between a Nimrod and an ordinary Sentinel. A single Nimrod can slap Juggernaut around, fend off the combined might of the X-Men and the Hellfire Club's Inner Circle, and hurt X-23 so badly her healing factor fails. Bastion dispatches five of them.

After what might be the most intense and harrowing battle sequence in the X-Men's entire history of publication, our bruised, battered, and maimed heroes return home to discover the Nimrod squad they fought was little more than a scouting party. More are on their way.

Second Coming reads like a fourteen-issue panic attack. It's relentless. It escalates and escalates and escalates, pushing the Children of the Atom to such extremities as haven't been seen before or since, and if these were books that put a premium on realism, the next two years' worth of issues would have been about everyone on Utopia struggling with acute PTSD.⁵ Second Coming is so intense and so masterfully realized, and given that its biggest flaws don't even occur within its pages, the next two crossovers on this list will both need to make a case as to why they deserve to be ranked above the culmination of Kyle and Yost's run on the X-books.

Most important development: Well, a few high-profile X-Men get killed, but that's not important. (More on this in a minute.) The main event is Hope returning to the present, delivering mutantkind from annihilation during its darkest hour, and apparently triggering new X-gene activations and mutant births, proving Cable and Cyclops right: she is indeed the mutant messiah.

And this is why I can't give Second Coming a higher ranking than number three: I know what comes next.

The key facts about Hope Summers are that she's the most powerful mutant, the most important mutant, and also a temperamental teenager with a teenager's recalcitrance against doing what she's told. The writers who inherited her from Kyle, Yost, and Swierczynski had to figure out the rest from there. I don't agree with the angry message board critics who complained about having Hope shoved down their throats, though I also wouldn't have argued with them. Hope really could have used more time to develop and ingratiate herself to people (on and off the page) before being thrust into the center of the X-books. Clearly Matt Fraction, Kieron Gillen, and company hadn't learned any lessons from X-Man in the nineties.

|

| Sweet Jesus, Mike Choi's artwork |

In the end, the anti-Hope crowd got their way. After Avengers Vs. X-Men, Hope was demoted from mutant messiah to a minor character, and her pals from Gillen's short-lived Generation Hope series pretty much disappeared. Hickman recently had the magnanimity to give her a spot on The Five, the group responsible for Krakoa's resurrection process—though she's very seldom seen on the page. In spite of all the sound and fury of her birth and ascension, Hope ended up mattering very little in the long run, which rather blunts the impact of Second Coming's crescendo.

Favorite moments: Warlock is such a sweetie pie that it's easy to forget what a powerhouse he can be when he wants to—like when he settles accounts with Cameron Hodge. As a kid, I was seriously not okay with Warlock getting killed off in X-Tinction Agenda, and this scene is so much red meat tossed out for people who'd been reading these damn books for at least twenty years. I won't say I didn't eat it right the hell up.

The strongest moment to earn its high score without pandering to thirty-something New Mutants fans would be Cyclops breaking down at Cable's funeral. Throughout Second Coming, Scott Summers is a rock. He never takes off his game face. He seldom gets emotional. I suspect he doesn't even sleep. When Beast screams in his face, he shrugs it off. When the Nimrods are on their way, he doesn't lose his composure. When old friends call him out for forming a secret assassination squad (X-Force), he lets it roll off him.

Then, when it's all over, he stands at the lectern to eulogize his son and finally buckles under the stress and grief.

Again, knowing what comes next somewhat takes the teeth out of moments like these. Cable returns to comic books a year later. Second Coming's other high-profile casualty, Nightcrawler, is brought back to the world of the living in 2014's Amazing X-Men. Ariel turns out not to have been dead after all; Vanisher is later seen unperforated and working with the Marauders without any explanation. Meanwhile, Karma and Hellion—who were merely dismembered instead of killed—got stuck with their prosthetics until Hickman's soft reboot.⁶

Superhero comics, everybody: where one can recover from being dead, but getting a leg ripped off is permanent. Let's face it: when Jason Todd, Doug Ramsey, Bucky Barnes, and Barry Allen were written back into continuity during the aughts, death officially ceased to have any meaning in superhero comics, and everyone knew it. When I got to the pages where where Bastion kills Nightcrawler in Second Coming's trade paperback, my first thought was: how long is this going to stick, and what are they going to contrive to bring Kurt back? In this regard, Hickman's introduction of the Krakoan resurrection protocols was a brilliant move: now that we've established an in-universe mechanism for mutants cheating death, the X-books can dispense with the artificial emotional shock of killing off and then mourning a character whom nobody reading expects will stay buried for long.

#2: THE X-CUTIONER'S SONG (1992–3)

Titles involved: Uncanny X-Men, X-Factor, X-Force, X-Men

Most important development: The Legacy Virus arc begins here, but let's face it: it didn't end up being that important. Mutants dropping dead of an AIDS metaphor made for some good plot thickening at the beginning, but a superhero serial isn't exactly equipped for a riveting treatment of a threat that can't be defeated by shooting optic blasts at it.

The most consequential turn in the X-Cutioner's Song is Cyclops learning that Stryfe is Nathan Christopher Summers—the infant son whom he gave up to Askani to be cured of Apocalypse's technovirus in the distant future—while Cable is a clone incubated as a failsafe in case the virus couldn't be cured.

But wait, that's not right: later on we find out that Cable is the original and Stryfe is the clone. That wasn't Nicieza's original intention, and I wouldn't be surprised if the idea was ultimately shot down for being way too dark. If you read the X-Cutioner's Song by itself, it's pretty obvious who's meant to be who, despite Stryfe's deferral from explicitly spelling it out for us.

It might also be worth pointing out that the X-Cutioner's Song contains the first time Rictor says Shatterstar's name. Ric rejoins his former New Mutants friends in X-Force #14. He speaks one sentence to Shatterstar in issue #15, before X-Force's face-off with the X-Men and X-Factor in X-Force #16. And it's seeing Shatterstar getting run through by Wolverine that makes Ric go ballistic. (In Logan's defense, Shatterstar was coming at him with a pair of swords, and has never been known for his restraint.)

We don't see him batting an eye when Rogue clobbers Boomer or when Strong Guy backhands Warpath into the air. But when Shatterstar gets hurt, then Rictor gets emotional and knocks out his old squeeze Rahne. Hmmm...

Favorite moments: Wolverine and Bishop hanging out with Cable on Graymalkin (especially when Peter David is writing it). Jumping ahead from the X-Cutioner's Song to Messiah War and seeing the three of them at each other's throats is awfully jarring; it's more fun when they're just being salty.

Speaking of cleaning up X-Force's messes, the Mutant Liberation Front (Liefeld's bastard Marauders) get the snot beaten out of them during X-Cutioner's Song's second act. It's satisfying purely as a BAM POW ZAP melee between comic-book superpeople, and even more delicious when read as an authorial guillotine brought down on a bunch of characters who weren't working out.

Lastly, I really dig dig the Stryfe's Strike File one-shot released at the end of the crossover. (1993: I saw the cover in the comic shop and bought it without even looking inside.) Presented as an index of the supervillain's personal logs, the book compiles the art and text of the collectible cards included with each of the crossover's twelve issues (how nineties), along with many additional entries on important figures in the X-Men's past, present, and future. It's a clever way for Nicieza and Lobdell to preview what's ahead for the X-books under their guidance (Stryfe's repeated allusions to his "legacy" inspire Professor Xavier to give that name to the bioengineered virus to which he refers), with Larry Stroman of X-Factor fame contributing most of the pin-up illustrations, and Nicieza getting an opportunity to write at length in his villain's purple prose. Craig Kyle and Chris Yost apparently liked this stuff so much that they brought back the "log-entry" inserts (in truncated form) for each bloc of their crossover trilogy.

#1: MESSIAH COMPLEX (2007–8)

Titles involved: New X-Men, Uncanny X-Men, X-Factor, X-Men

In brief: The first post-Decimation mutant is miraculously born. As in the parable of Solomon, everyone shoots, stabs, mauls, and beats the hell out of everyone else until the last party standing gets to keep the baby.

The long story: On the face of it, 2005's House of M was primed to celebrate the ten-year anniversary of Age of Apocalypse by reenacting it in concept and execution, though gussied up with a utopian sheen in lieu of a hell-on-earth matte black. All of the X-books were to flip into an alternate reality for a few months, then flip back out when our heroes inevitably set things right and restore the world to the way it was before. But there was one major difference between Age of Apocalypse and House of M. After Age of Apocalypse, the only lasting in-universe consequences were the arrivals of Nate Grey and Dark Beast into mainstream continuity, and a bunch of retcons involving Genosha and the Morlocks. In the wake of House of M, the population of Homo superior is reduced from several million to a couple hundred, and the X-gene has become altogether inactive in the procreation process. Back to normal, indeed.

Judging from the message board chatter I've observed over the years, Decimation has to be one of the least beloved events in the X-books' history. I remember grabbing the X-Men: The 198 Files promo one-shot off the rack in the bookstore out of morbid curiosity and perused it with a scoff and a sigh. It had been a very long time since I'd kept up with happenings in the X-Men's soap opera, and I couldn't say I regretting losing track. What a dumb idea for a publicity stunt this was; how deeply it undermined the X-Men's central premise by turning mutants from an embattled minority to an endangered species; and how convenient that most of the mutants to keep their powers just so happened to be familiar costumed adventurers and ne'er-do-wells. Pfeh!

But there's no denying that some great stories came out of Decimation. Peter David's new and improved X-Factor and Craig Kyle and Chris Yost's brilliant, all-too short run on New X-Men (not to be confused with Grant Morrison's New X-Men) come to mind. Three of the crossovers we've already looked at (Utopia, Messiah War, and Second Coming) occurred post-Decimation, and all of them developed in its wake. And now here's a fourth: Messiah Complex. Say what you will about Decimation, but without it, the all-time best X-Men crossover story (so far?) could not have happened.

Much of the praise Messiah Complex garnered during its release pertained to its evocation of classic X-Men. Despite coming at the end of a decade that had seen the franchise turned inside-out and upside-down, Messiah Complex felt old-school. Its rogues' gallery may have been a factor: after returning for Messiah Complex's prelude in the pages of Mike Carey's X-Men, the Marauders are back in action and scarier than they've been since their Mutant Massacre debut. Mr. Sinister, who had diminished in stature during the aughts, is once again at the top of his game. Finally daring to show his face after embarrassing himself by appearing at the climax of Chuck Austen's stupendously bad run, Exodus has reassembled his Acolytes (with nineties leftovers Tempo and Random joining their ranks), and thrown in his lot with Sinister. Deathstrike allies herself with the Purifiers, upgrading a squad with cybernetics and dubbing them her new Reavers.

More significant than the familiarity of Messiah Complex's villains is that of its format. The X-books didn't do many crossovers during the aughts (actually, I'm struggling to name a single one), which may have had something to do with post-Onslaught events like Operation: Zero Tolerance and Apocalypse: The Twelve failing to meet expectations. Moreover, a proper crossover story, by all accounts, is onerous to coordinate. It's easily dragged down by a weak book in the mix, and conversely, a weak crossover can drag a good book down. Conscription into a crossover can be frustrating for a book's creative team (as Peter David will tell you), forcing them to put whatever they were doing on hold for a few months to compose chapters for a story that wasn't their idea. It's easy to understand why Marvel and DC began shying away from the crossover format in favor of staging their big events as limited series (Infinite Crisis, House of M, Civil War, Blackest Night, etc.), while dedicating the ongoing monthlies associated with them to "companion" stories. As a matter of fact, before Messiah Complex, the most recent X-Men crossover to have been executed on a similar scale had been the X-Cutioner's Song.

Though I hadn't occasion to mention it above, the X-Cutioner's Song deserves bonus points for providing Messiah Complex with its template. Consider the similarities in their structures. They begin with a disaster and a desperate manhunt; their plots trace the unraveling of a mystery. Most of the superpowered action scenes consist of team brawls between rival factions with their own stake in the game. Between the blown-out fistfights, a subplot follows two X-characters traveling far from home to gather information, and uncovering the clue that makes the difference between success and failure. At the climax, the plotlines all converge in the ruins of a site haunted by past traumas. And so on. Eerily specific similarities abound too: Cable becomes a persona non grata, Professor Xavier gets shot, insubordinate X-teens get into trouble, images from old-school X-Factor's Endgame arc flit across the climax, and a team called X-Force has a special role to play. Then there are the funny coincidences, such as the oddball artist: while the artwork in both crossovers is fairly consistent between chapters, there's one penciller in each whose work saliently clashes with the rest. The X-Cutioner's Song has Jae Lee's extravagant grittiness, while Humberto Ramos brings his anime-inspired style (and unwholesome preoccupation with Omega Sentinel's butt) to Messiah Complex.

Like the X-Cutioner's Song, Messiah Complex's plot consists of an evolving conflict between three groups, with Cable as the wild card. Cyclops and the X-Men want to take the newborn "mutant messiah" under their protection. Mr. Sinister wants to use the baby to further his hideous eugenicist ends. Matthew Risman's Purifiers will do whatever it takes to kill the "mutant antichrist." Cable already has the baby, and doesn't intend to give her up. To make matters more interesting, each faction has somebody with their own agenda. Bishop, ostensibly working with the X-Men, wants to find and kill the baby to erase the dystopic future timeline in which he grew up. Mystique, serving under Sinister, sees her employer as she sees everyone but her daughter: as a means to an end. And Predator X, the Purifiers' "organic Sentinel"—well, he's just out to eat the kid, and does pretty much whatever he wants in the meantime. We could tediously dissect the sub-factions within each of the three factions if we wanted—but it will suffice to say that Messiah Complex is par for the crossover course in that there's a lot going on.

One of Messiah Complex's strengths is in giving all the representatives of its books something to do, dispatching them in different directions during the first act, and playing to the strengths of each. The card-carrying X-Men brawl with the Acolytes and Marauders in their search for the baby. A band of Xavier Institute students go off on their own to take the fight to the Purifiers. Jamie and Layla from X-Factor visit a future timeline to gather intelligence about what might be about to happen. Naturally, not one damn thing goes according to plan.

Without committing myself to a drab plot summary, I'm not sure what else we can say about Messiah Complex. It's not terribly deep—but that's not why we're reading superhero books, is it?

Though I am little acquainted with professional wrestling, I am aware of its points of contact with mainstream capes comics: if you enjoy and appreciate one, you have some understanding of the other. For instance, much of Roland Barthes's famous essay about wrestling—"its natural meaning is that of rhetorical amplification: the emotional magniloquence, the repeated paroxysms, the exasperation of retorts can only find their natural outcome in the most baroque confusion"—applies equally well to X-Men comics. Their actors, their conflicts, their relationships, and the abstruse contexts in which they confront one another are so exaggerated—such pure and high-proof distillations of the emotions, impulses, and self-delusions undergirding everyday experience—that they approach not only mythological dimensions, but the threshold of the euphoric.

The strange thing about Messiah Complex (and many of these other stories) is that it's about desperation, violence, betrayal, and loss—and yet it's a delight, page after page. Larger than life, convoluted yet eminently legible, and too earnest in its ridiculousness not to take seriously. Like the best superhero rags, it's an amalgamation of Greek drama, Roman games, and a drag show, staged as a sui generis color-print extravaganza.

I'm beginning to doubt that a "literary" analysis of Messiah Complex (or any other comic book event) would turn up proof as to what might elevate it above its peers: an examination of superhero comic books is a study of spectacle. Sometimes the actors just have a really good night, the members of the freeform jazz band fall deep into unified groove, or both pugilists in a prize bout fight the best they ever have before. It's a matter of verve and aplomb in the execution: difficult to quantify, but unmistakably palpable. I can only hope that some of whatever juju was haunting the X-books' creative teams during Messiah Complex will be seen animating X of Swords.

Most important development: Speaking as someone who exclusively followed DC Comics for fifteen years, I've lost count of the number of promos promising AFTER THIS THING, EVERYTHING WILL BE DIFFERENT—FOREVER, only for the big event arrive at a conclusion where maybe one big-deal character dies and/or becomes evil (Final Crisis, Event Leviathan), or with a kooky and obviously temporary renovation of the status quo that gets reversed after a year or two (Infinite Crisis, Forever Evil). Messiah Complex is not such an event. The only other crossover on this list to have the same kind of impact on the X-books is Fatal Attractions, and that one was a linewide reorientation disguised as a story. Some of Messiah Complex's direct consequences were the relocation of Uncanny X-Men to its new San Francisco setting under Matt Fraction, the rebranding of Mike Carey's X-Men as the Xavier-centric X-Men Legacy, the cancellation of New X-Men, and the launch of Craig Kyle and Chris Yost's X-Force, Duane Swierczynski's Cable, and (sigh) Marc Guggenheim's Young X-Men.

Probably the character who comes out of Messiah Complex the most changed is Cyclops. In an earlier story, Professor Xavier and Cyclops had a falling-out. We won't delve into the context (you can read X-Men: Deadly Genesis if you're really curious to know), but the upshot is that for a year or so of publication-time, Cyclops has lead the X-Men and headed the Institute, while Xavier lurks on the premises and pursues his own projects, quietly enlisting sympathetic former students to help him out. In Messiah Complex, this uneasy joint-custodial truce concludes when Cyclops finally gives his mentor the boot. Cyclops officially becomes top dog, and Xavier begins a (temporary) backslide into irrelevance.

Moreover, Messiah Complex marks the point where Cyclops begins his tilt towards separatist revolutionary. He's the leader of a people under siege, and has no choice but to become ruthless in protecting them. This is, after all, the story where the new-and-improved X-Force makes its debut as Cyclops's secret handpicked assassination squad. In fact, I believe I may have located the very panel where Scott Summers begins breaking bad:

Can you imagine Cyclops flat-out ordering Wolverine to murder people in the eighties or nineties? Me neither. But Scott has been through an awful lot since then.

Oh, yes: a decade and a half after his 1991 debut as a time-displaced cop trying to sniff out and foil a traitor who destroys the X-Men from the inside, Bishop shoots Xavier in the head in a desperate attempt to kill the infant mutant and change (his) history. Irony!

When I began reading X-Men comics (the very first issue I owned was Uncanny X-Men #292, for the record), Bishop quickly became my favorite character. Not that I could have articulated my reasons at the time, but I liked him because he was smart, tough, disciplined, and determined...and he had a lot of giant guns from the future. And yet I didn't feel like my childhood had been betrayed when I read his heel-turn in Messiah Complex. Sure, it would have been more convincing if Bishop's anticipation of the child's birth had gotten even a fleck of foreshadowing—but if we wanted to be charitable to the authors of a decades-long serial written with little long-term aforethought, we could rationalize the omission by noting that Bishop obviously has the intelligence and self-control to keep delicate information to himself. To read Bishop the way Swierczynski thought of him in his Cable series, we just need to appreciate that what he's doing is giving—and enacting—his answer to the old "if you could go back in time and kill Hitler" hypothetical dilemma.

Favorite moments: I'm going to limit myself to just two items. Otherwise I might find excuses to keep adding more. In case you hadn't noticed, I kind of really like Messiah Complex.

Though I didn't read it until long after its cancellation, Kyle and Yost's run on New X-Men might be my single favorite phase of any X-book. I don't know why this is. Maybe it's because the central group assembled from members of Academy X's analogues to Gryffindor and Slytherin has such great dynamics, both in terms of their personalities and as a squad of superpowered heroes-in-training. Maybe it's because the book cannily exploits the ages of its characters to heighten the intensity of their relationships and feelings while also refraining from infantilizing them. Maybe it's the Evangelion fan in me that gets a vaguely sick-to-the-stomach thrill watching teenagers being forced into horrible and desperate situations that would break most adults. Maybe I just enjoy watching the cast of the "Harry Potter but also X-Men" serial of the early 2000s getting traumatized into maturity after Kyle and Yost took the authorial reins from Nunzio DeFilippis and Christina Weir.

Without going into a bootless rant about the book that replaced New X-Men (Guggenheim's Young X-Men) and what a pile of garbage it was, I've never completely gotten over my disappointment that Surge, Hellion, Mercury, Dust, etc. were downgraded from starring roles to the occasional cameo appearance. They were great characters in an excellent ensemble.

At least Kyle and Yost find the time in Messiah Complex to wring out the closest thing we'll ever get to a conclusion to Surge's character arc. We learn that Emma Frost didn't select Surge to lead the new recruits to punish Hellion for disobeying her, but because she honestly believed Noriko was the best choice. When Surge singlehandedly holds off Predator X to give the other students time to escape, she proves both her mettle and her worthiness to lead. It's just too bad Guggenheim elected to eliminate her position shortly afterward.

My second favorite moment needs no exposition. It was 2009: I was working at the bookstore and lurking in the graphic novels section during my break. I noticed the Messiah Complex trade paperback on the shelf and opened it up. "Oh, let's see what they're doing to the X-Men these days," I said to myself. "I still have ten minutes left on my break."

I ended up coming back five minutes late. I couldn't put it down. I lost track of time. For a moment I felt like I was nine years old again, reading the X-Cutioner's Song for the first time—absorbed in the spectacle, not quite comprehending what was happening, and enjoying the pitched, smoky drama all the more for the mysteries it teased. Holy crap, I thought, when did X-Men comics get good again?

1. The outlines for Messiah Complex (published in the X-Men Milestones edition) refer to Wolverine's squad as the "War Pack." Either this was placeholder designation, or it really was going to be the title of Kyle and Yost's new book until an editor stepped in. As a bit of dialogue, the "assemble the X-Force" line that made it to print in Messiah Complex comes off a lot more awkwardly than "assemble the War Pack" would have. I'm willing to bet someone just did a ctrl+f substitution in the script at the last minute, replacing the noun without deleting the article, and the letterer simply wrote what the document instructed him to. Yes, this sort of thing stands out to me.

2. Did we mention that N'astrih was also responsible for making Cameron Hodge's head immortal? He gets around, that N'astrih.

3. Zeb Wells is currently writing the new Hellions series. So far, it's quite good, even if Julian Keller is nowhere to be found.*

* This is as good a place as any to mention that even though the new volume of X-Factor made a somewhat poor first impression on me (it's clearly written to make people on Twitter clap for it), it may already have redeemed itself by finally bringing back Wind Dancer, Keller's paramour from the New X-Men: Academy X days. I'm hoping she sticks around.

4. I hated X-Men Evolution until I decided I really liked it.

5. To my immediate recollection, its only competition consists of the Dark Angel Saga, the Fall/Rise of the New Mutants, and the Generation Next limited series.

6. I'm guessing that Elixir restored Shan's leg and Julian's hands off-panel. I'll throw out another guess and say that Kyle and Yost put Elixir out to pasture after Necrosha because having a get-out-death free card on hand would have considerably lowered the stakes in Second Coming.

I'm curious, have a top ten worst X-men events? I don't know the precise order for mine, just that X-men VS Inhumans is on there somewhere, mostly highlights just how badly Disney was treating the X-men at that point.

ReplyDeleteNah. I mean, I'd never take the time to systematically determine and set in order the ones that annoyed me most. Most of them would be from the last decade. Inhumans Vs. X-Men for the reason you mentioned. Rosenberg's run on Uncanny was just abysmal. The teenaged O5 settling in the present was bad, and the storyline that sent them back home, introduced Kid Cable, and somehow brought Cyclops back was just as stupid. Age of X-Man had a good moment or two, but it was obviously done to make a few sales while stalling for time before Dawn of X. Etc, etc.

DeleteHow well do you think these books would land on an X-neophyte? They sound like a ton of fun, but...

ReplyDeleteAnswered via DM, but on the off-chance that somebody else is curious: the answer is no, but it's really not that big of a deal. Pretty much everyone who reads X-Men comics picked their first issue off the rack and started without knowing what the hell was going on. You just kind of roll with it and keep reading until you figure things out, and honestly, that's part of the fun.

DeleteThanks for this, I enjoyed it quite a bit.

ReplyDeleteSure thing. I read hundreds of issues during the lockdown and had to do something to get 'em out of my brain.

Delete