|

| René Magritte, Natural Encounters (1945)¹ |

This is going to be the last time I post about Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (1781–87) for the foreseeable future. Thank god. I'm ready to be done with it—even though I doubt it's done with me. This is a book one can exhaust a lifetime studying, and I still haven't plumbed it to the uttermost depth of its mysteries. But there are other books to read and ideas to ponder, and it's about time I moved on.

I feel I should reiterate that I'm not writing this to lecture an imaginary audience about Kant, but to help myself get my own head around the Critique. Don't take anything I say as authoritative, and do please correct me if you have some familiarity with the material and catch me misinterpreting it.

Our last post about Kant is about the Transcendental Dialectic—which is, in fact, twice as long as the Transcendental Aesthetic and the Transcendental Analytic. Fortunately, it's a lot easier to understand on the whole—though in its particulars, it's as deep a rabbit hole as the other two sections.

While the Transcendental Aesthetic was a statement of the principles underlying Kant's transcendental logic, and the Analytic was a statement of those principles, the Dialectic applies them to some of the pressing metaphysical and philosophical questions of Kant's time—or, rather, to some of the proposed answers to those questions.

This brings us to something really scary about the Critique of Pure Reason: you have to give a close reading to three hundred pages of dense, onerously-phrased epistemology before arriving at the "critique" part. As a matter of fact, nothing that we've glanced at in the last six posts about this damn book have had anything to do with the Transcendental Dialectic.²

To return for a moment to the Scholasticism-tinged schematics that inform Kant's model of the human mind (ie., a diagram of perception and cognition in which separate "faculties" govern specific mental functions), the Transcendental Dialectic (finally) makes a clear distinction between the understanding and reason, terms which might have appeared synonymous to the unguided reader up until now. The understanding sorts perceptions into categories, organizing objects of immediate experience. (The categories, the pure concepts of the understanding, are the a priori organizational "templates;" other categories, like "animal," "mineral," and "vegetable" are acquired a posteriori.) Reason, on the other hand, may be said to constitute the organizing principles that manage the understanding.

This is all very perplexing to me and my physicalist sensibilities. Maybe a few excerpts will help clear things up.

[1] In the first part of our Transcendental Logic we explained the understanding as our faculty of rules, and we now distinguish reason from understanding by calling it the faculty of principles.

[2] If the understanding is a faculty for producing unity of appearances according to rules, then reason is the faculty for producing unity of the rules of the understanding under principles.

[3] Manifoldness of rules and unity of principles is indeed a requirement of reason, for the purpose of bringing the understanding into thoroughgoing coherence with itself, just as the understanding brings the manifold of intuition under concepts and thus brings intuition into connection.

[4] Reason, if considered as a faculty of a certain logical form of knowledge, is the faculty of inferring, that is, of judging mediately (by subsuming the condition of a possible judgement under the condition of a given judgement).

[5] Reason never refers directly to an object, but only to the understanding, and through the latter to its own empirical use. It does not, therefore, create concepts (of objects), but only orders them, and imparts to them that unity which they can have in their greatest possible extension, that is, with reference to the reality of different series; while the understanding does not concern itself with this totality, but only with the connection whereby series if conditions everywhere come into being according to concepts.

[5] may be read as the implication of [1] through [4]: the understanding concerns physical objects and "thought-objects," while reason deals with them only indirectly. Within our body of understanding, reason is the ligature that binds and organizes concepts (while concepts determine and organize experience).

|

| René Magritte, The Reckless Sleeper (1927) |

If any of us remember how Kant sussed out the twelve pure concepts of the understanding from the relations of logic (in its eighteenth-century formulation), we probably won't be surprised to learn that he revisits syllogistic logic in order to figure out the essential principles of reason:

We will find as many pure concepts of reason as there are kinds of relations, which the understanding represents to itself by means of the categories; and we will have to look for an unconditioned, firstly, of the categorical synthesis in a subject; secondly, of the hypothetical synthesis of the members of a series; thirdly, of the disjunctive synthesis of the parts of a system.

Good ol' Immanuel: when he's at his most pithy, he's absolutely incomprehensible to the reader who hasn't been following him for three hundred pages. Let's go over some terms.

The unconditioned is that which is not contingent, and designates what we could call the final "because" at the end of an explanatory regress. Imagine a child asking her father "why is the sky red during the sunset?" He might answer something like "because of atmospheric light scattering." Then our inquisitive child asks "why does the atmosphere scatter light?" If our father has read a few physics textbooks, he could say "because when a photon interacts with matter, it brings atoms into excited states, which then release that energy in the form of other photons which are released in amounts and at energy levels randomly determined by the energy level of the original photon and the atoms' quantum numbers." "Why?" the child asks. "Because," her father says, reaching for his phone and bringing up Wikipedia.

The unconditioned is the last "because" in the line, and gets its name because this last "because" is absolute. We could translate "unconditioned" to herself as "unconditional," and get the gist of what Kant's getting at. (I'm sure there's a razor-thin distinction between the two concepts that Kant would insist upon, but in a basic overview like this, it won't make too much of a difference.) And it is reason's natural and unavoidable tendency to seek the unconditioned:

[P]ure reason leaves everything to the understanding, which initially refers to the objects of intuition, or rather their synthesis in imagination. It is only the absolute totality in the use of the concepts of understanding that reason reserves for itself, while trying to carry the synthetic unity which is thought in the category up to the absolutely unconditioned. With regard to appearances we may therefore call the latter unity the unity of reason, and the former unity, which is expressed by the category, their unity of understanding. Hence reason refers only to the use of the understanding, but not insofar as the latter contains the basis of possible experience (for the absolute totality of conditions is not a concept that can be used in experience, because no experience is unconditioned), but in order to prescribe to it a direction toward a certain unity——a unity of which the understanding knows nothing and which is meant to comprehend all acts of the understanding, with regard to any object, into an absolute whole.

Kant rather takes this tendency as self-evident—and at least for now, let's assume he's not wrong. Human curiosity, as popularly characterized, leads us to seek explanations for what we observe and experience in the world. When we view a data chart, we're rarely content to accept that "it is what it is" and move on. We want to interpret it. We want to explain why the data is what it is. From a Kantian perspective, this is the faculty of reason goading us on. This is also the basis of the "law" of induction: our generalizing that all A's are B, even though we'll never experience all A's that ever existed or will exist, ensues from our reason's innate tendency to unify objects of the understanding.

Kant maintains that reason naturally makes sense of the world by hypostatizing our concepts, and I cannot dispute this. Although Kant lived a couple centuries before "isms" marched as a phalanx across our intellectual landscape, he would have certainly observed that we have a hard time making sense of something like racism unless we treat it as a thing that people have instead of as a description of a social dynamic. Though we err in doing so, our reasoning faculties haven't actually misfired: in fact, they're functioning perfectly normally. We see Events A, B, and C (an act of police brutality, an off-color joke, a microaggression) as related in that they instantiate some common principle, and that principle becomes an object in and of itself. Kant suggests that this is precisely how the physical sciences produced the concept of force.

|

| René Magritte, Mental Complacency (1950) |

The Transcendental Dialectic isn't concerned with investigations into any specific empirical phenomena, but with the way reason urges us towards assumptions about the transcendent—which, in typical Kantian fashion, means something completely different from the transcendental. The transcendental deals with the possibility of experience—with human capacities and limits. The transcendent is or seeks to go beyond those limits. Get it? But then Kant defines the transcendental idea as the erroneous application of reason into areas which are beyond the understanding—ie., into the transcendent. (Eesh.)

Human beings, Kant believes, inevitably concoct transcendental ideas about three particular things. More on those in a moment.

When Kant nominates three types of synthesis involved in the operations of pure reason—the categorical, the hypothetical, and the disjunctive—he's referring to terms of Aristotelian syllogistic logic, which doesn't see much application these days and is mostly of interest to historians.³ Fortunately for those of us who didn't study the trivium and quadrivium in our university days, this stuff is pretty easy to look up.

• You know what a categorical syllogism looks like because you've seen them before. A typical instance would be:

- Some A are B

- All B are C

- Therefore, some A are C.

• A hypothetical syllogism involves conditional statements:

- If A, then B

- If B, then not C

- Therefore, if A, then not C

• A disjunctive syllogism involves an "or" statement:

- A or B

- Not A

- Then: B

Let's ignore for now any misgivings we might have about the entirety of human reason boiling down to these three forms of logical operation. If we have a hard time swallowing that, then we're certainly going to object to this:

The universal in all relations that our representations can have is (1) their relation to the subject; (2) their relations to objects either as appearances or as objects of thoughts in general. If we combine this subdivision with the above division [the three forms of syllogistic inference], we see that all relation of representations, of which we can form either a concept or an idea is threefold: (1) the relation to the subject; (2) the relation to the manifold of the object in appearance; (3) the relation to all things in general.Okay. So far, so good. Whatever I experience, I experience either/or in relation to myself, in relation to other things in the world of phenomena, or in relation to everything. Prima facie, none of this is ridiculous. But then:

All pure concepts in general aim at a synthetic unity of representations, while concepts of pure reason (transcendental ideas) aim at unconditioned synthetic unity of all conditions in general. All transcendental ideas, therefore, can be arranged in three classes: the first containing the absolute (unconditioned) unity of the thinking subject; the second the absolute unity of the series of conditions of appearance; the third the absolute unity of the condition of all objects in thought in general.

So from those three forms of syllogistic proposition, Kant extrapolates the human propensity for believing in the soul, for setting or removing limits to the age and size of the universe, and for belief in God (the psychological, cosmological, and theological transcendental ideas). It appears somewhat more plausible after Kant presents his receipts (though I'm sure grad students have made auditing them the basis of their dissertations), but for the purpose of keeping this tolerably short, let's just assume he's on the up and up.

|

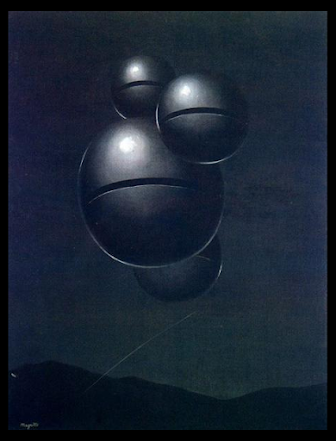

| René Magritte, The Voice of Space (1928) |

If you've been keeping track, these ideas represent what Kant calls the unconditioned: each can be considered the final "because" in a chain of metaphysical reasoning. If we ask ourselves about the nature of mind and selfhood, we're likely to end up at a concept of the soul. Questions about the causes of events in the world follow a regress back to speculations of a definite beginning (or the "fact" of no beginning). If we ask why the universe is constituted the way it is, intimations of an immanent rationality in the design of the cosmos touch off speculations of an architect (which may be a transcendent rational principle in and of itself).⁴

The very, very, very short explanation is that reason, in seeking to bring the ineffable into unity with the rest of our knowledge, wants to apply concepts that are only valid for objects of possible (immediate) experience to things beyond experience, and thus unknowingly wanders into error. For example: I feel that the self I experience is not a continuity of interrelated physical events, but some essence existing at those events' substratum. That essence is a thing, and I call that thing a soul—and then I write and publish reams of metaphysical treatises speculating as to where the soul comes from, where it goes after my body expires, and whether it will retain my consciousness and the memories of my life. I'd be mistaken in all this—and yet innumerable people more educated and intelligent than me have taken precisely this route. With religion it is generally the same: we all observe that events have causes, and reason has a natural proclivity for interrogating nature for an original cause. If left to its own devices, reason will not be impeded by the inaccessibility of the series' beginning.

The main mass of the Transcendental Dialectic (and the actual "critique" component of the Critique of Pure Reason) is a systematic dismantling of metaphysics. We are inaccessible to ourselves; the self we experience is, like everything else in the world, an appearance, and thus we can have no knowledge of ourselves as things-in-themselves (read: the soul). Concerning questions about whether the universe had a beginning, whether it extends forever, or whether free will exists, Kant demonstrates that perfectly logical arguments can be made for any of these propositions; therefore, the whole question is bogus because it's unanswerable.⁵ And he absolutely savages the rational theologians' "proofs" of the existence of God (insofar as demanding that existence not be misapplied as a logical predicate can be characterized as "savage"), and denies that God is a thing of which we can have any actual knowledge one way or the other.

But there's a tremendous caveat to all of this, which Kant states in the Critique's preface:

I had to suspend knowledge in order to make room for belief.

Kant employs no words for which he doesn't have a specific meaning in mind, and "belief" (Glaube) is no exception. In both of its forms (pragmatic and moral), we can take it to mean provisional knowledge: a judgement made on grounds that are neither proven nor unproven, and emerging from subjective necessity. My materialistic view of the world is a pragmatic belief: I can neither prove nor disprove the existence of spirit, but I find I can make better sense of things and (hopefully) act more effectively if I take its nonexistence as fact.⁶ My idea that every human being deserves dignity and a decent standard of living is a moral belief: I'll never be able to draft an incontrovertible scientific proof of it, but I'll still say I believe it must be true.

This is how Kant navigates between the reckless metaphysics of the "dogmatic spiritualists" and the soulless universal mechanism of scientific materialism: his epistemology altogether denies the possibility of gaining definite knowledge of anything that transcends sensory experience, with the caveat that believing certain transcendental ideas (to a reasonable extent) carries both practical and moral benefits.

This will be the second-to-last long excerpt from the Critique of Pure Reason, and is worth reading in full:

If, then, it can be shown that the three transcendental ideas (the psychological, cosmological, and theological), although they are not referred directly to any object corresponding to them, or to its determination, yet lead, as rules of the empirical use of reason and under the presupposition of such an object in the idea, to a systematic unity and to an expansion of our empirical knowledge, without ever running counter to this knowledge, then it becomes a necessary maxim of reason to proceed in accordance with such ideas. And this is the transcendental deduction of all ideas of speculative reason, considered not as constitutive principles for extending our knowledge to more objects than can be given by experience, but as regulative principles for the systemic unity of the manifold of empirical knowledge in general. Thus this knowledge, within its own limits, can be cultivated and improved better than would be possible without such ideas, and by the mere use of the principles of the understanding.

I shall try to make this clearer.⁷ Following these ideas as principles, we shall first (in psychology) connect all appearances, actions and receptivity of our mind, according to our inner experience, as if our mind were a simple [irreducible] substance, existing permanently and with personal identity (in this life at least), while its states, to which those of the body belong only as external conditions, are changing continually. Secondly (in cosmology), we are bound to follow up the conditions both of inner and outer natural appearances in an investigation that can never become complete, as if nature were in itself infinite and without any first or supreme member; but we ought not therefore to deny, outside of all appearances, the merely intelligible first grounds of nature, although we must never bring them into connection with our explanations of nature, for the simple reason that we do not know them in the least. Thirdly, and lastly (in theology), we must consider everything that may belong to the context of possible experience as if that experience formed an absolute unity but a thoroughly dependent one, and one that is always——within the world of sense——still conditioned, and yet also, at the same time, as if the sum total of appearances (the sensible world itself) had, outside its sphere, one supreme and all-sufficient ground, namely, and independent, original, creative reason——a reason, in reference to which we direct all empirical use of our reason, in its widest extension, as if the objects themselves had sprung from that reason. In other words, we ought not to derive the inner appearances of the soul from a simple thinking substance, but must derive them from one another according to the idea of a simple being; we ought not to derive the order and systematic unity of the world from a highest intelligence, but must borrow the idea from the idea of a supremely wise cause the rule according to which reason, when connecting causes and effects in the world, may best be used to its own satisfaction.

We see this in action all the time in the physical sciences. Whether an astrophysicist is conscious of it or not, she works under the assumption of an intelligible cosmos, as though the universe were a message that must be read, translated, and continuously retranslated to bring the text nearer to a perfect fidelity to its author's intention. Economists and sociologists, too: it is absolutely impossible to arrive at a total understanding of human events, but they cannot conduct their studies without conceiving of an endpoint (complete demystification) towards which their efforts are directed (or so Kant attests).

|

| René Magritte, Pure Reason (1948) |

The same disciplines also afford examples of what happens when transcendental illusions are allowed to prevail. String theory (or M-theory), which purports to be a unified theory of everything, has produced (supposedly) excellent mathematics but not one iota of empirical evidence: as theoretical physicist Peter Woit says, it's "not even wrong." And yet, it still has its enthusiastic backers in academic and popular science, and millions of dollars are still being funneled into researching something that's as incapable of being an object of empirical study as the human soul. In the social sciences, misdiagnoses of what racism actually is and how it works (ie., hypostatizing racism as something people have, identifying a constellation of unrelated events and objects in the environment as being the same thing—racism—and having the same cause and necessitating the same solutions, etc.) have created a multibillion-dollar industry whose main beneficiaries are wealthy academics and corporate consultants whose recommended programs apparently don't work.⁸ Elsewhere in identity discourse, one wonders if the conversation might be a little less acrimonious if "gender" was identified as something a person enacts, rather than something they possess.

The point Kant keeps repeating is that the steps reason takes toward bringing our nebulous empirically-derived concepts of the world into a systematic unity are regulatively beneficial, but some of the ways in which our faculties are programmed to go about doing that—confounding conceptually associated objects as members of a uniform species, reifying ideas of systems as ideas of subjects, overextending the principle of induction, and so on—result in the formation of spurious constitutive ideas of the world: reified concepts and formulaic mental shortcuts masquerading as definite knowledge of objects. Belief in a rational universe was and is a necessary prerequisite for investigating natural phenomenon, but reason oversteps its bounds and acts at cross-purposes to its own ends when its speculations carry it to presumptions of any possibility of direct (or even inferential) knowledge about whatever entity, principle, or force might be responsible for the ordered laws of nature.

But on the "god" question, Kant heartily endorses faith in a supreme being as a morally necessary belief. We know that he isn't a fan of rational theology, but he feels very differently about moral theology:

[Moral theology] enables us to fulfill our destination here in the world by adapting ourselves to the system of all ends, without either fanatically or even criminally abandoning the thread of a morally legislative reason in the proper conduct of our lives, but in order to connect this thread directly with the idea of the highest being.

These remarks appear in the Transcendental Doctrine of Method, the Critique's final section, which concerns the methodology of the principles outlined in the Transcendental Aesthetic, Analytic, and Dialectic. The Doctrine of Method is fun to chew on, and far less esoteric than the six hundred or so pages preceding it.⁹ Kant jumps around a bit, comparing and differentiating philosophical knowledge from mathematical knowledge, elaborates on the differences and relations between knowledge, belief, opinion, and conviction, outlines a history of philosophy, discusses the "architectonics" of systematic theorizing, and—perhaps most significantly—begins to flirt with the ethical implications of his doctrine.

The moral theology Kant briefly sketches in the Transcendental Doctrine of Method is presented as an oblique consequence of his epistemology and metaphysics: like Aristotle, Kant holds that human reason must have some final practical end, and that end can only be happiness. And happiness is most reliably achieved through morality—a morality that is informed by and which harmonizes with reason.

I call the world a moral world, insofar as it may be in accordance with all moral laws (which according to the freedom of rational beings it can be, and according to the necessary laws of morality it ought to be). As here we abstract from all conditions (ends) and even of all impediments to morality...this moral world is thought as an intelligible world only. It is, therefore, to this extent a mere idea, though at the same time a practical idea, which really can and ought to exercise its influence on the world of sense, in order to bring it, as far as possible, into conformity with this idea....

Earlier, Kant defined the law of morality as "worthiness to be happy," and claims it is extrapolated from experience—but doesn't present much detailed evidence.

The answer to [the question "what ought I to do?"] is this: Do that which will render thee worthy to be happy. The second question asks: How them if I behave so as not to be unworthy of happiness, may I hope thereby to obtain happiness? The answer to this question depends on whether the principles of pure reason which prescribe the law a priori, necessarily also connect this hope with it.

I say, then, that just as the moral principles are necessary according to reason in its practical use, it is equally necessary according to reason in its theoretical use to assume that everybody has ground to hope for happiness in the same measure in which he has rendered himself worthy of it in his conduct, and that, therefore, the system of morality is inseparably, though only in the idea of pure reason, connected with that of happiness....

With mere nature as our ground...the necessary connection of a hope for happiness with the unceasing endeavour of rendering oneself worthy of happiness cannot be known by reason; rather, it can only be hoped for if a highest reason, which rules according to moral laws, is accepted at the same time as underlying nature as its cause.

Which leads us back to God:

As we are bound by reason necessarily to conceive ourselves as belonging to [a moral world], although the senses present us with nothing but a world of appearances, we shall have to accept the moral world as being the result of our conduct in the world of sense (in which we see no such connection between worthiness and happiness), and therefore as being for us a future world. Hence it follows that God and a future life are two presuppositions which, according to the principles of pure reason, cannot be separated from the obligation which that very reason imposes on us.

I have no comment on any of this—mostly because ethics and moral law are the subjects Kant addresses in much greater detail in the Critique of Practical Reason (1788).

...Or so they say. I haven't read it yet. Right now I'm planning to wait till the spring to get started.

|

| René Magritte, Clear Ideas (1958) |

Hmm. This wasn't an especially meaty post, was it?

I hadn't any alternative but to gloss over the Transcendental Dialectic: omitting it would be out of the question, but treating it thoroughly would necessitate another seven entries. I must reemphasize: people have written their doctoral theses on the Transcendental Dialectic. It is exceedingly chonky, too intricate and massive for a pat Cliff's Notes treatment. And I admit I feel an obligation to examine it more deeply—again, not for the sake of impressing or entertaining an audience, but simply to better understand it.

The Critique of Pure Reason is a storehouse of riches. Even if you can't approach Kant as a disciple, he demands to be answered as a challenger. He's too precise, too thorough, and too brilliant to be written off as a bloviating egghead, and his theories are germane to anyone with a healthy intellectual curiosity. As I mentioned in a footnote to one of the first posts in this series, much of modern philosophy exists as a continuation of the conversation that Kant jump-started with the Critique.

Has Kant swerved me? To some extent: I won't know for sure until I think and/or write about some other perplexing topic and discover how useful a cipher transcendental idealism actually is—which is why I need to step away from the Critique for a good long while.

1. Today we've conscripted René Magritte to serve as our eye-confectioner. It seems fitting for the section of the Critique which expatiates on transcendental illusions.

2. I think I can be forgiven for getting hung up on Kant's epistemology. It's a lot to process.

3. (I) Many pages later, Kant derives from these three principles of forms: homogeneity, specification, and continuity. Reason is always on the lookout for these, and imposes them upon objects of experience (via our concepts of them). (II) Idea for future Kant post if the urge strikes me: Kant's belief that human reason is essentially syllogistic. That warrants examination.

4. From the concluding remarks of the Transcendental Dialectic: "it must be the same to you, when you do perceive this unity [read: rational cosmic order], whether we say, God has wisely willed it so, or nature has wisely arranged it so."

5. Living in the eighteenth century, Kant couldn't have known about, say, the cosmic background radiation adduced as proof of the big bang theory. However, Celia Green's statement on cosmology still basically holds up: "time had a beginning" and "time did not have a beginning" are both fundamentally inconceivable, as are "the space around the Earth extends infinitely" and "the space around the Earth does not extend infinitely."

Dr. Green has this to say about Kant in The Human Evasion (1969): "Kant gives the impression that he liked the inconceivable, but his books are too long."

6. This also applies to Kant's own transcendental idealism. While Kant insists we are absolutely unable to know whether the world as our senses perceive it actually corresponds to the world that's really out there, there is no harm whatsoever in provisionally accepting that it is the same in appearance as it is in reality as a matter of belief. We can never find any evidence to the contrary, nor will we ever uncover proof that conclusively affirms us. (When Kant writes about how reason "soars" when it brings itself to bear on "the wonders of nature and the majesties of the cosmos," one suspects he's not in the habit of reminding himself that a starry vista of a summer night is merely a perceptual apparition determined by the way his own mind works.)

7. Oh, Immanuel. Why start now?

8. Regarding the parenthetical remark: this being a personal blog, I suppose there's not much shame in citing a piece from Medium:

Another potential problem is that very different problems can get grouped under the same umbrella as well. So for example, the reasons black women can’t find much makeup at the drug store (very small percent of the population, generally with less money) are very different from the reasons that a girl’s father flips out when she brings home a black man (lack of experience and a fear of “the other”, dog whistle racism by his preferred political party, etc.) And yet both of these things are just referred to as “racism”. Sure, if you go back far enough, some of these problems may have common causes——but some of them don’t. And often, the best way to remedy the makeup problem has nothing to do with the best way to remedy the father problem. But in social and academic circles, we hear people discussing “combatting racism” [sic] as though it were a unified goal unto itself.

This is all totally beside the point, but I thought it might be a good idea to clarify what I meant.

9. Actually, there were a few lines that I'm pretty sure appear verbatim in Introduction to Logic (1800), a short little book of posthumously published lecture notes. It was my introduction to Kant, and is a much better entry point to his ideas than the Critique of Pure Reason.

Well...that was one wild ride that took me to the edge of reason so to speak. Its...gotten me to ponder about if I'm being reasonably reasonable...though some of the stuff is still over my head.

ReplyDeleteWell...speaking of challenging god...sort of...I was just curious if you ever might do a article on Xenogears like you did with Chrono Trigger and Cross? Xenogears had a big impact on me I suppose with storytelling, even if like Cross it did not leave as big a impact as its staff might have hoped...Well, just curious between Xenogears...Kingdom Hearts or Final Fantasy 7 's remake which of those would be the one most likely for you to write about, they all have aspects of how Square went overboard to various extents to me lol.