Games, like institutions, are extensions of social man and of the body politic, as technologies are extensions of the animal organism. Both games and technologies are counter-irritants or ways of adjusting to the stress of the specialized actions that occur in any social group. As extensions of the popular response to the workaday stress, games become faithful models of a culture. They incorporate both the action and the reaction of whole populations in a single dynamic image.—Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media (1964)

Of course, "games" meant something totally different in 1964 than today. But the good professor is still worth listening to on the topic, I think.

So, once again, we're examining the technical and cultural backdrop of a silly YouTube video where a couple hundred different animators set new moving pictures to the old noises from two of the most embarrassing video games ever made.

This seemed like a such a good idea a month or two back. I was drinking more back then. Early winter and all.

MYTHS: THE MUTATIONS OF NARRATIVE

Who are the mythmakers?

First, it depends on what we mean by "myths." We'll come back to that.

Second: it depends on how a culture is organized, and the technology it uses.

When we talk about the emergence of tales, histories, fables, and other such verbal constructions that instruct through metaphor, contextualize things and events by involving them in a narrative, or simply give pleasure to a listening audience, we're at a disadvantage relative to the biologist: she has the benefit of being able to dig up and examine physical specimens of prehistory to expand her knowledge. But the first tale of Coyote told on the American continent, the first mention of the bard Orpheus in Greece, the origins of Baba Yaga in the Slavic world—all were speech events, and as such left no material traces of themselves.

Still, scholars have been able to learn and infer much about the conditions under which such orally transmitted narratives were developed and transmitted from generation to generation by studying extant nonliterate or semiliterate cultures.

In nomadic hunter-gatherer cultures, members of a society typically don't fall into specialized roles (beyond those imposed by the sex-based division of labor), and a group is therefore unlikely to have designated storytellers, priests, etc.—although a person with a knack for spinning yarns is apt to have a better time in life. Settling down in a fixed location apparently lays the foundation for the differentiation of functions, leading to the development of the designated teller of tales, or interlocutor with the supernatural. (Among the Tsimané of Bolivia, adults usually possess most of the life skills appurtenant to their sex, but older men in particular tend to fit into "a late life niche emphasizing information transmission.")

We will make four further generalizations about the making and transmission of stories in a primary oral culture:

1. Traditional tales abound with pedagogical content. The astonishing mnemonic capabilities shown by people of nonliterate societies have an upper limit; the density of practical information, helpful aphorisms, moral examples, etc. contained in a story can help to ensure its transmission over the long term.

2. The stories of a primary oral culture will be intensely local, containing specific information about regional flora, fauna, geography, etc.¹

3. Orality is interactive and present. The storyteller calibrates his or her performance according to the audience, and responds to feedback. Walter Ong provides an example in his opus Orality and Literacy (1982):

[T]he editors of The Mwindo Epic...call attention to a similar strong identification of Candi Rureke, the performer of the epic, and through him of his listeners, with the hero Mwindo, an identification which actually affects the grammar of the narration, so that on occasion the narrator slips into the first person when describing the actions of the hero. So bound together are narrator, audience, and character that Rureke has the epic character Mwindo himself address the scribes taking down Rureke’s performance: 'Scribe, march!' or 'O scribe you, you see that I am already going.' In the sensibility of the narrator and his audience the hero of the oral performance assimilates into the oral world even the transcribers who are deoralizing it into text.

4. Orality tilts conservative. Here we ought to quote Ong at length:

Since in a primary oral culture conceptualized knowledge that is not repeated aloud soon vanishes, oral societies must invest great energy in saying over and over again what has been learned arduously over the ages. This need establishes a highly traditionalist or conservative set of mind that with good reason inhibits intellectual experimentation...[O]ral cultures do not lack originality of their own kind. Narrative originality lodges not in making up new stories but in managing a particular interaction with this audience at this time——at every telling the story has to be introduced uniquely into a unique situation, for in oral cultures an audience must be brought to respond, often vigorously. But narrators also introduce new elements into old stories...In oral tradition, there will be as many minor variants of a myth as there are repetitions of it, and the number of repetitions can be increased indefinitely. Praise poems of chiefs invite entrepreneurship, as the old formulas and themes have to be made to interact with new and often complicated political situations. But the formulas and themes are reshuffled rather than supplanted with new materials.Religious practices, and with them cosmologies and deepseated beliefs, also change in oral cultures. Disappointed with the practical results of the cult at a given shrine when cures there are infrequent, vigorous leaders...invent new shrines and with these new conceptual universes. Yet these new universes and the other changes that show a certain originality come into being in an essentially formulaic and thematic noetic economy. They are seldom if ever explicitly touted for their novelty but are presented as fitting the traditions of the ancestors.

Such is the state of affairs when the lore and world-narratives of a people have not been outered via technological means: stories are integrated with a group's praxis of life (to borrow a phrase from Peter Bürger), bound up in relational networks of locality and common experience, directly transmitted from speaker to a proximate audience, and don't place a premium on novelty or disruptive innovation for their own sake.

One final note about primary orality comes from Jack Goody and Ian Watt's "The Consequences of Literacy" (1963), and suggests something about a conception of "genre:"

Non-literate peoples, of course, often make a distinction between the lighter folk-tale, the graver myth, and the quasi-historical legend. But not so insistently, and for an obvious reason. As long as the legendary and doctrinal aspects of the cultural tradition are mediated orally, they are kept in relative harmony with each other and with the present needs of society in two ways; through the unconscious operations of memory, and through the adjustment of the reciter's terms and attitudes to those of the audience before him.

This is something we touched on in an earlier iteration of these "Flowers" writeups: whatever story is being told is understood to be integrated and in agreement with the rest of the tales one has heard and can repeat. Without a written record of Narrative X and Narrative Y to check against each other for consistency, the minor discrepancies that would bedevil a literate theologian or comic book fan are apt to pass undetected.

|

| Nyanga mask (early 19th century) |

The convoluted difficulty of early writing systems testifies to how far from obvious to the ancients was the possibility of reducing the whole resonant universe of spoken language to a small number of abstract symbols. With respect to the business of mythmaking, the investment of time and resources required to train a person to read and write in cuneiform or Egyptian hieroglyphics fostered knowledge monopolies and the entrenchment of priest castes as arbiters of a people's mythology.² The "official" narratives of the gods and the cosmos came under elite control, but it stands to reason that the peasantry continued circulating traditional stories whose origins lay outside the temples. William Butler Yeats and Zora Neal Hurston's transcriptions of tales from rural Ireland and the black population of the Southern United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries attest to the persistence of folklore and storytelling under similar circumstances.³

We'll not dwell on the diffusion of alphabetic writing systems based on the Phoenician script, except to say that it tended towards the democratization of literacy—with the caveat that this tendency mustn't be overstated. If literacy no longer belonged exclusively to priests, scribes, and treasurers, it was still a skill in which only a small portion of the population was trained.

|

| Cuneiform tablet (Hymn to Marduk), detail (ca. 1st millennium BCE) |

European manuscript culture retained many characteristics of orality that were later sloughed off in the centuries after the invention of Gutenberg's printing press. For one thing, the concept of intellectual property was still a long way off: to reproduce a text was considered a high compliment to its author, not theft; the medieval student was "paleographer, editor, and publisher of the authors he read."⁴ The vernacular literature produced in this time was intended to be read aloud to an audience; HJ Chaytor points out that characterization in medieval literature may appear bland and stiff to modern readers because there's a missing piece: the theatrics of the performer who'd be reading to us in the text's in situ context.⁵ In a sense, reading Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (14th century) or Canterbury Tales (ca. 1400) privately, in silence, is like playing Duck Hunt, Wild Gunman, or any other light-gun arcade shooter on an emulator with a mouse, or watching a silent film unaccompanied by a pianist's performance.

Most important to us here is the continued lack of invention on the part of authors. This is not to say the medieval period lacked creativity by any measure, but it tended to draw from folklore, history, and extent texts rather than do much of what we would call "world building." The Spanish Cantar de mio Cid (ca. 1140–1207), the Arthurian cycle, the Charlemagne matter, etc. were all romanticized treatments of renowned historical figures. Dante's Divine Comedy (1320) synthesized classicism, scholasticism, and Italian politics into a narrative journey through the Catholic afterlife. Boccaccio's Decameron (ca. 1353) draws its plots from various textual sources, which can probably be traced back to orally transmitted folklore, as does Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, which also draws from the Decameron.⁶ The storytelling conventions of manuscript culture preserved much of orality's communality and conservatism.⁷ European chirographic culture recorded, reproduced, integrated, added, and elaborated—but it didn't manufacture myths.

|

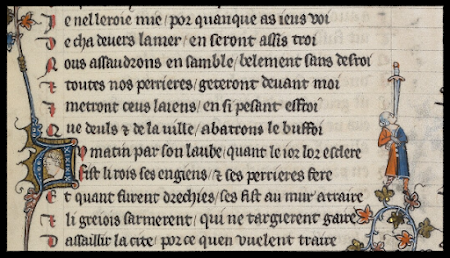

| Alexander Romance (Manuscript Bodley 264), detail (ca. 1338–1410) |

The printing press couldn't satisfy the public's demand for literature before creating it—gradually. Just as the world wide web and its users weren't capable of producing a Homestuck, a language of memes, or an influencer caste right after the 56K modem hit the market, proto-print culture took some time to get its bearings, as Harold Innis explains in The Bias of Communication (1951):

As the supply of manuscripts in parchment which had been built up over centuries had been made available by printing, writers in the vernacular were gradually trained to produce material. But they were scarcely capable of writing large books and were compelled to write controversial pamphlets which could be produced quickly and carried over wide areas, and had a rapid turnover. The publisher was concerned with profits. The flexibility of the European alphabet and the limited number of distinct characters, capable of innumerable combinations, facilitated the development of numerous printing plants and the mobilization of a market for a commodity which could be adapted to a variety of consumers. Knowledge was not only diversified, it was designed by the publisher to widen its own market notably in the use of advertising.

Hrm. The more things change...

Once it became possible for a writer to have his material distributed without the laborious process of manually copying individual codices, and once the literate part of the urban population became accustomed to buying new reading material, the cycle began reinforcing itself. Transcriptions of sermons, play scripts, broadsides, and song sheets were the closest thing to "popular" literature in early modern England; scholars estimate that around 600,000 different single-sheet ballads were in circulation in the second half of the sixteenth century. (Note that most of these texts were either intended to be read aloud or were records of oral events.)

Samuel Pepys' famous Diary (1660–69) sometimes makes mention of "telling of tales" during social occasions; more often he, his wife, and his friends entertain themselves by playing instruments and singing. Frequently he mentions sitting around and reading—plays, histories, philosophy, essays, prose romances, scientific treatises, and apparently the occasional satire ("a merry book against the Presbyters called Cabbala, extraordinary witty"). Pepys was born to a middle-class family, studied at Cambridge, and was employed as a naval administrator while he wrote his diary, so he's far from a representative specimen of the seventeenth-century English population. But nevertheless, a layman like him two centuries earlier wouldn't have been poring over books so frequently.

|

| From the printed ballad Robin Hoods progresse to Nottingham (ca. 1623–61) (sung to the tune of "Bold Robin Hood") |

The printing press, originally employed in the mass production of bibles and indulgences, didn't break Christianity's grip upon Western consciousness over a single generation, but print technology was instrumental in rousing Europe from its spell. The pagan texts that the medieval monastics (and Dante) gingerly adapted to a Christian context were read with a somewhat more porous doctrinal filter by the laypeople of Renaissance Italy. The printing of vernacular bibles fomented the Protestant schism, shattering the unity of the Western church. Newton drew upon a wealth of knowledge from books that would have been scattered and scarce prior to their reproduction and dissemination via print technology; with a print run of some hundreds of copies, the Principia (1687) reached a far larger audience in a far shorter a time than would have been possible had it been subject to the conditions of medieval manuscript production and use.

The scientific revolution, instigated by Newton, chipped away at Christian cosmology and the vestiges of scholastic natural philosophy, while the luminaries of the Enlightenment promoted an ethos in which the inerrant text of the Bible wasn't necessarily to be considered the wellspring of all truth. The churches preserved enough of their medieval clout that an accusation of atheism was still a thing to be feared, and the place of the chapel was too much a fixture in social life to permit the flock from straying en masse; but insofar as we're talking about the evolution of myth and lore, it's useful to bear in mind that the printing press' role in challenging the absolute credibility of Christian doctrine while simultaneously populating the imagination of an increasingly literate public with more abstract figures and events than those given to them by history, legend, and religious tradition.

|

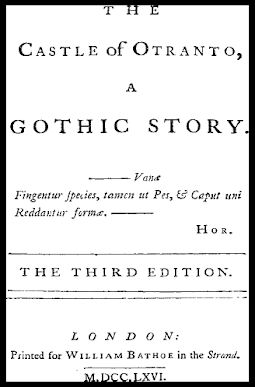

| Title page of Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto (1764) |

During the nineteenth century, the market's ravenous appetite for prose fiction, the mercenary avidity of publishers, and the unprecedented speed and efficiency given to the production and distribution of print matter by steam technology conspired to deliver mass media (and with it, the culture industry) unto the world. The novel gained cultural currency concurrently with the economic and political rise of the bourgeoisie, and told original stories calibrated to middle class sensibilities. This was the age of "literary realism," speckled with colors of the Romantic or Gothic. The novels of Charles Dickens (whose celebrity cannot be understated), Anthony Trollope, Guy de Maupussant, Gustave Flaubert, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy, Bolesław Prus, et al. (and good god, we could go on) would have struck a medieval audience, prima facie, as ignoble and frivolous: "somebody wrote a six-hundred page narration, (in prose!) of burghers milling about and talking to each other, and we're supposed to be entertained?"

At any rate, by the nineteenth century, popular tastes had advanced far beyond stories about Robin Hood, Charlemagne, minor heroes of Greek mythology, the lives of the Saints, and so on. Ghost stories and romantic narratives still had an audience, and science fiction would join the field toward the end of the century—but for the most part, the reading public had decided that it most enjoyed novels about itself and society.

The mythological consciousness (to use a crude term) of the West had become fragmented. Secular histories, religious chronicles, ongoing narratives of current events, a growing body of fictional literature, scientific materialist and sacred conceptions of the world, what was seen, heard, and felt in the world and what was read on the page—all of it crowded in people's heads like standoffish roommates sharing a small apartment. By degrees, the harmoniously integrated world-narratives of pre-literate humanity had been divaricated into unrelated and often irreconcilable segments.

Marshall McLuhan:

From that magical resonating world of simultaneous relations that is the oral and acoustic space there is only one route to the freedom and independence of detribalized man. That route is via the phonetic alphabet, which lands men at once in varying degrees of dualistic schizophrenia.⁸

|

| Fernand Khnopff, I Lock My Door Upon Myself (1891) |

Here we should pause to talk another look at the words "mythology" and "myth. Like "art" and "nature," they have no consistent material referent, and are laden with the baggage of multiple contexts of use, not all of which are compatible.

If a mythology consists of no more than stories of supernaturally gifted heroes performing fantastic feats of strength, cunning, and bravery in a world of gods and monsters, then sure: the works of both Ovid and Stan Lee fall under the category of mythology. But if the word instead refers to an overarching narrative—a network of relations mantling the order of the world, defining the remote and unseen causes of phenomena, and grounding one's identity in a mesh of abstract associations—then it becomes harder to call Marvel or Harry Potter a mythology in the same way the lore of the Olympians and national heroes constituted the mythology of the ancient Greeks. Compounding the difficulty here is the unease we might feel if, granting that Marvel Comics counts as a mythology, we then went on to state that Avengers Vs. X-Men is a myth, or a mythic episode.

If we insist that a mythology of the second type satisfy some arbitrary standard of coherence across any area of experience to which it may be applied (in other words, that it be the universe of discourse for both a person's understanding of the cosmos and of their social identity), or that the stories one "consumes" or "uses" in their everyday life relate in a fairly clear and linear manner to their overarching conception of the world and their role in it, then we'd have to conclude that "mythology" is nowhere to be found in the affluent world today. Having externalized our faculties through the use of media technologies whose content and form are in a state of permanent volatility, we've fractured our consciousness, entangling ourselves in a snarl of mutually exclusive abstract relations.

This is to say we operate with a patchwork mythology. As we evolve media (it is gross to say "as media evolves"), each media form conditions our habits of cognition and perception along different lines—which is what McLuhan means by "schizophrenia." In a heterogenous and inconstant media environment, it is too much to ask that a particular mythos be as pervasive and orderly as medieval Christendom's great chain of being, or even the Taoist/Confucian/Buddhist syncretism of feudal China.

We'll return to this. But in any case, the prevailing "mythology" in a place like nineteenth-century Great Britain would have been a composite of history, national identity and destiny, protestant/bourgeois morality, scientific materialism, etc. The extent to which popular fiction not only entertained and perhaps edified readers, but entered into their overarching personal narratives regarding themselves and the world, is somewhat hard to gauge, though there was a slight moral panic about women getting addicted to novels—a concern reflected by characters like Emma of Madame Bovary (1857) and Izabela of Lalka (1889), whose reading habits colored their ideas of what reality is or ought to be like, and interposed a barrier between them and their peers. (Both books were written by male novelists, of course.) To judge Emma and Izabela as "delusional" is a harsh way of saying that each has a separate point of view—only remarkable for the fact that they deviate so far from the norm.

Such discrepancies between text and social reality weren't restricted to fiction. As we've seen, the ephemerality of information in an oral culture precludes collocation and analysis. This is obviously not the case in a developed literate culture: Innis notes that by the fourth century BCE, "the spread of writing checked the growth of myth and made the Greeks sceptical of their gods."⁹ During the unprecedentedly rapid social and technological changes of the nineteenth century, the incongruities between the knowledge inherited from the past and declared in the present, and between customary belief and the facts of experience, drove some to distraction. It was precisely this growing awareness of a pervasive dissonance in the Western consciousness that engendered the early stirrings of modernism in the arts and letters.

|

| Gustav Moreau, The Apparition, detail (ca. 1874–76) |

Irrespective of McLuhan's theories about the sensorium, the society whose members take in information and entertain themselves by sitting alone and reading quietly partakes in a form of mass culture as discrepant from "tribal" orality as from twenty-first-century digital nativism. The "content" of print matter, for which the visual sense is the mere form of intake (the content of an image is the image itself, whereas the content of a poem is not the shapes and configuration of the ink on the page per se), has no object in the world of common experience. For the advanced silent-reader, the words she reads may not always trigger the response of conditioned hearing. The content of print is private and utterly abstract.

Two people talking about the Shakespeare play they read the night before (quietly, alone in their own homes) probably won't have as animated a discussion as the couple leaving the theater after seeing a performance of the same play. For that matter, discussions about books follow a completely different track than conversations about movies. Plays and films are sensuous events; we might also call them objective. You and I see and hear the same Marlon Brando. But the Ahab I may "hear" speaking in Moby-Dick (1851), and the tattooed body of Queequeg I might "see," are assuredly nonidentical to the Ahab and Queequeg of your experience.

Does this apply to orally transmitted tales? To some extent, sure—but the nonarbitrary physical attributes of the oral performance are more proximate to the "content" of the story than are the printed letters of its transcription. Three different groups of fifty people listening to the same elder unwind the story of an ancestor on three separate occasions have more in common regarding their concrete experience of the tale than 150 people reading, say, the Penguin Classics edition of the Epic of Gilgamesh (ca. 2100–1200 BCE) by themselves. A group of friends attending a recording of Selected Shorts (or a couple catching the broadcast in the car) who listen to somebody read a short story by Dorothy Parker will have a richer memory of the story than somebody who reads it by herself: during the readings, the story is "in" a sequence of events in space and time, and conditioned by the presence of people with whom she has a social bond, and who, colloquially speaking, will share her memory of the occasion, and can speak of it in vivid terms that will be fairly consistent with her own recollection.

This is not to rank one medium of information transmission or storytelling above or below any other. Think of the number of times you've heard somebody sigh "the book was better" during a conversation about a movie. However, since we are animals shaped by the contingencies of survival to "instinctively" perceive and react to movements, sounds, intensifications and diminutions, etc. in the environment, and had to be trained to derive meaning from static sequences of visual symbols, the sensuous media have a certain inbuilt advantage over print with regard to their capacity to seize and command our attention.

The print paradigm produced a state of affairs where people stayed abreast of events in society by disengaging from society to read about them, and experienced cultural events (say, the release of a new Dickens novel or reports from a military operation abroad) in isolation from the people whose customs, activities, and relations constitute culture. Information, literature, and the belles-lettres were transmitted and engaged with as phenomena of private experience. But print's tendency to promote social fragmentation could be somewhat countervailed by the incentives to discuss what one reads with his friends, family, and colleagues (fear of missing out can't be peculiar to our own time), by inducements toward participation in religious and civic institutions, and by print matter's limited capacity to stimulate the senses. After all, one wants music! One wants to hear people speak, to look them in the eyes, to see things happening in the world! Electric media can provide a serviceable imitation of these things; print cannot.

But, in tandem with a confluence of historical developments (namely the industrial revolution, when capitalism hit puberty and had its prodigious growth spurt), print contributed to the lacerations cleaved in the West's social tissues. It was during the second half of the nineteenth century that subcultures became possible. Two contributing factors were the temper of urbanism and the conditions of Gesellschaft (though it is difficult to consider them independently), under which communal social ties and obligations were superseded by the impersonal dictates of civil law and economic contracts—under such circumstances, where one can be an anonymous face in the crowd, deviance from the norm is less often noticed or discouraged.¹⁰

Goody and Watts explain the contribution of the print paradigm to cultural splintering:

First, because although the alphabet, printing, and universal free education have combined to make the literate culture freely available to all on a scale never previously approached, the literate mode of communication is such that it does not impose itself as forcefully or as uniformly as is the case with the oral transmission of the cultural tradition. In non-literate society every social situation cannot but bring the individual into contact with the group's patterns of thought, feeling and action: the choice is between the cultural tradition——or solitude. In a literate society, however, and quite apart from the difficulties arising from the scale and complexity of the "high" literate tradition, the mere fact that reading and writing are normally solitary activities means that insofar as the dominant cultural tradition is a literate one, it is very easy to avoid....

[E]ven when it is not avoided its actual effects may be relatively shallow. Not only because, as Plato argued, the effects of reading are intrinsically less deep and permanent than those of oral converse; but...the essential way of thinking of the specialist in literate culture is fundamentally at odds with that of daily life and common experience; and the conflict is embodied in the long tradition of jokes about absent-minded professors.

The second paragraph may be relevant later. But the first makes clear the instrumental role of a robust book market and widespread literacy in promoting the growth of subculture. If one didn't care for the books his family and former classmates were reading, he could read something else—putting himself on a different page from them, as it were.

The nineteenth century was the beginning of Bohemianism in Paris; it was the age of the detached flâneur and the Decadent movement. Russian novels like Turganev's Fathers and Sons (1862) and Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov (1880) feature characters who have fallen out of sync with traditional culture after stints in the academy. In his 1852 novel Pierre, Melville describes a community of artists and writers housed in an old church converted into small apartments; Melville spills considerable ink describing them in terms of their reading habits:

Their mental tendencies, however heterodox at times, are still very fine and spiritual upon the whole; since the vacuity of their exchequers leads them to reject the coarse materialism of Hobbes, and incline to the airy exaltations of the Berkelyan philosophy. Often groping in vain in their pockets, they can not but give in to the Descartian vortices; while the abundance of leisure in their attics (physical and figurative), unite with the leisure in their stomachs, to fit them in an eminent degree for that undivided attention indispensable to the proper digesting of the sublimated Categories of Kant; especially as Kant (can't) is the one great palpable fact in their pervadingly impalpable lives.¹¹

It probably isn't inaccurate to call this a feedback loop: the cultural and social contortions of the nineteenth century and the proliferation of print material mutually conditioned one another. The relationship between alienation and mass media has ever been one of reciprocity.

|

| Fernand Léger, Charlot Cubiste [Cubist Charlie Chaplin], (1924) |

It would be entertaining to speculate as to how things would have progressed if, somehow, the printed word remained the world's only mass medium for another hundred years. But within the span of half a century, it was joined by the gramophone, radio, the silent film, the "talkie" (which deserves to be categorized separately from its mute predecessor), and broadcast television. We could also add the comic book and newspaper comics page to the list on the basis that neither was a viable mass medium until photomechanical printing techniques made them inexpensive, and that words embedded in images operate differently on us than images embellishing text.

An analysis of how the sudden diversity of the mass media landscape fragmented and desynchronized the culture of the developed world between 1900 and 1960 is far, far beyond the scope of what we can accomplish here. But we can sum up some important developments.

The phonograph and radio carried the music of black subcultures in American cities to international audiences, initiating the displacement the tavern song and sheet music ditty as the prevailing forms of popular music. The silver screen—wherein "the exactitude of reality and its surprising power of suggestion are to be had for the asking," wrote Virginia Woolf in 1926—created a secular pantheon of stars and starlets whose images circulated with more range and greater fecundity than the iconographic representations of Achilles and Theseus on Grecian urns. The cinematic cartoon, executed with an ever increasing level of sophistication, bathed audiences in moving, speaking hyperreality, where talking deer gamboled in meadows that never existed in this world (but there they nevertheless were, moving and speaking in living color, clear as day!). By the 1940s, the penny dreadfuls, dime novels, and pulp anthologies that had became popular at the turn of the century faced fierce competition from comic books, and then comic books were in turn imperiled by television during the 1950s. Poetry became irrelevant; Print fiction began to disappear into the cultural background, forced to repurpose itself from a popular general-audience medium to a pastime for children in one-television households, an ever-shrinking segment of the cognoscenti, and bored people on vacation. And so on...

The original question—who makes the myths?—has grown complicated.

To recap: in a nonliterate, "primitive" culture, the creation and retention of a mythology is a communal endeavor and pleasure. The stories, histories, and practical knowledge of a people cannot even be called "common property," since they exist in no fixed, external forms. When writing emerges as a prosthetic extension of memory, accessible only to those who have been trained to use it, it is possible for an "official" mythology of the gods and the nation to be administered by a "knowledge worker" caste that hands down from above what was once passed along through more lateral social channels.¹² The illiterate can preserve a tradition of folklore where there is space to do so.

As we've seen, some of the first popular texts to come off the printing presses in England were sermons, ballads, and plays: the cultural residue of orality and the fledgling state of the market precluded demand for wholly novel "content." The relationship between the speaker/printer of a transcribed sermon and his readers was pretty that between the proverbial preacher and the choir. Printed ballads were typically composed to the tune of traditional songs, and were full of the same references to the same Greco-Roman and Italian literature, regional folklore, and Christian themes that pervaded Canterbury Tales. Plays stringently adhered to custom, and theater troupes had an existential interest in not pissing off the church or the royal censor.

Print culture's protracted effects on the old myths was largely destructive Those that had the best chance of thriving in the modern environment were the more abstract and narrow sorts of mythology we usually call ideologies. The construction of new mythoi could only begin after mass media became sensuous. The effects of text may be relatively shallow, as per Goody and Watts, but electric media's are veritably mesmeric.

There are any number of economic inflection points that might represent the moment when the culture industry came into maturity, but a characteristic of the change that's more difficult to quantify and to pin down (though no less significant) is that suppliers rose to a position where they could create demand—influencing their audience's taste instead of servilely catering to it. On the eve of television's conquest of the world, Adorno and Max Horkheimer already understood the dynamics of its reign:

If the objective social tendency of this age is incarnated in the obscure subjective intentions of board chairmen, this is primarily the case in the most powerful sectors of industry: steel, petroleum, electricity, chemicals. Compared to them the culture monopolies are weak and dependent. They have to keep in with the true wielders of power, to ensure chat their sphere of mass society...is not subjected to a series of purges. The dependence of the most powerful broadcasting company on the electrical industry, or of film on the banks, characterizes the whole sphere, the individual sectors of which are themselves economically intertwined. Everything is so tightly clustered that the concentration of intellect reaches a level where it overflows the demarcations between company names and technical sectors. The relentless unity of the culture industry bears witness to the emergent unity of politics. Sharp distinctions like those between A and B films, or between short stories published in magazines in different price segments, do not so much reflect real differences as assist in the classification, organization, and identification of consumers. Something is provided for everyone so that no one can escape; differences are hammered home and propagated. The hierarchy of serial qualities purveyed to the public serves only to quantify it more completely. Everyone is supposed to behave spontaneously according to a "level" determined by indices and to select the category of mass product manufactured for their type.¹³

The people who make the myths in a society with an entrenched laissez-faire philosophy pertaining to cultural production as well as to material exchange will be the same people who make (or, rather, own the means of making) everything else. When the production and dissemination of "art and literature" is left to the free market, the tendency of capital to become consolidated in fewer and fewer hands eventually places the publisher and the studio under the control of the megafirm. (Columbia Pictures was owned by the Coca-Cola Company in the 1980s; AT&T owns Warner Bros.; MGM is in the process of being bought by Amazon; every publishing imprint you can think of is owned by Bertelsmann; and so on.) If, by one definition, myths are the stories that are important to us, that bring us together and help us to make sense of the world, then the answer is: the myths are made by the people whom capital employs to make them.

Sure, yes, this is certainly true if the definition of "myth" we're going by pertains to the likes of Hercules, Spider-Man, and Marilyn Monroe. But what about the myth-as-world-narrative? What about cosmology, metaphysics, and teleology? What about history? What about matters of the spirit?

Amazon ands its ilk don't own the schools or churches just yet. But maybe they don't have to.

|

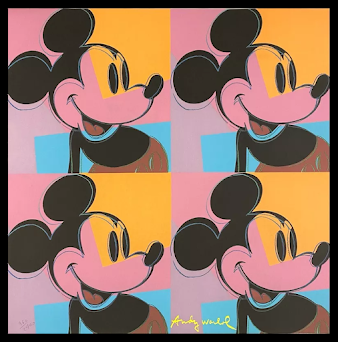

| Andy Warhol, Quadrant Mickey Mouse (1986) |

Entrenched public institutions like schools and churches stand contraposed to the culture industry—not in the sense that their interests are necessarily opposed, but in that they're sustained through different means than private or corporate businesses. They're not participants in the free market. Nevertheless, they still find themselves locked in competition with corporate media.

Having once been an unhappy middle-school student myself, I can imagine how it must have been for an eighth grader in the late 1960s. Central figures of the national mythology—the likes of George Washington, Davey Crockett, and Thomas Edison (who in age past would be the subjects of folktales and bards' songs)—confronted the student as calcified data, inert in the textbooks, while the crew of the Starship Enterprise (or at least its television-manifested simulacrum) is meantime audibly and visibly present when the TV is switched on in the evening. While "real" history is narrated by a stentorian teacher who demands respectful silence, assigns tedious homework assignments, and punishes people who squirm too much at their desks, Captain Kirk and his crew make their own history in the the appearance of real time.

Under such conditions, far less work must be done to make somebody intellectually and emotionally invested in Abraham Lincoln on a long-term basis to encourage them to verse themselves in James Kirk's life and career—fictional though they might be.

By the same token, without direct guidance (and threats) from family, authority figures, and social influences, a young person is more likely to find more significance in the martyrdom of Obi Wan Kenobi than the martyrdom of Christ. All things being equal, a young person of the late 1970s and early 1980s experienced Star Wars as something much nearer to an actual event than bible readings and Sunday school lessons, one which would have been seen to have a expansive and eminently perceptible impact on his peer group and society at large than the fall of Jericho or the Sermon on the Mount. (It hardly needs be said that sitting through Star Wars is more stimulating than sitting through church, besides.) Unless care was taken to insulate him, or to strongly impress upon him the significance of the quiet, sacred history and the triviality of the loud, commercial spectacle, the "true" mythology of his forebears' religion was prone to being superseded in his worldview by the synthetic mythology of a Hollywood film and its sequels.

(Are indifference to history and religion guarantors of social collapse? Who knows. Maybe not necessarily. But overall, the aggregate mythos of electric media is a spiral of self-reference that cites the past and depicts the spiritual, subsuming them into its splintered, dissociative metanarrative.)

|

| Damien Hirst, Mickey (Blue Glitter) (2016) |

Given the existence of Trekkies, Star Wars fanatics, and Comic Book Guys prior to the dial-up modem, we probably can't say that the world wide web caused the spread of fandoms. But it certainly accelerated it, and was undoubtedly the decisive factor in their normalization.

There might have been other factors. I'll admit that I have no hard data to back this up, but it seems obvious that twenty- and thirty-somethings in the 1980s were, in the aggregate, less enthusiastic about comics, cartoons, video games, etc. than the twenty- and thirty-somethings of the 2010s. My father, born in the 1950s, watched cartoons and read comic books as a child, and owned an Atari 2600 in his early thirties (though I didn't often see him playing it, and it disappeared before I turned three). It's probable, I think, that improvements made to these media between the decades of his youth and mine at least partially account for him abandoning his old toys while I've clung more to mine. There's a difference between being a watching Yogi Bear and Speedy Gonzalez cartoons as a seven-year-old, and watching Dragon Ball Z and Invader Zim at the same age—just as there's a difference between watching the Buck Rogers film serial and watching the Star Wars trilogy, and between playing Pong and playing Legend of Zelda.

The novel was popular enough in the eighteenth century to warrant an entry in Diedrot's Encyclopédie (1751–66), but longform prose fiction didn't realize its latent potential until the nineteenth century. Tolstoy's sublime War and Peace (1867), the greatest novel ever written, couldn't have been composed in the eighteenth century because the cultural determinants weren't there. On the other hand, Star Wars couldn't have been made in 1940, and Ocarina of Time couldn't have been made in 1980, because the technology didn't exist, while cartoons like Batman: The Animated Series, Animaniacs, and X-Men were the outcome of outsourcing practices and advancements in animation production in East Asia. The speed at which electric media strides forward is a function of corporate investment.

The franchise was one of those strides. It's easy to imagine somebody who read The Amazing Spider-Man as a preteen in the 1960s losing interest when the comic remained almost tediously consistent, the 1967 television cartoon was tripe, and the 1977 live-action series was impossible for anyone over the age of thirteen to take seriously. But the kid who read Batman in the early 1980s would have seen the comic book brand spawn a pair of edgy, intelligent graphic novels, an acclaimed Tim Burton film, an epochal animated series (with its own feature films and multiple spinoffs), video games, etc., many of which double back and influence the course of the ongoing Batman monthlies as they continuously evolve in an unabating effort to suit the mood and tastes of the times. The more media in which Batman routinely appears, the more effectively the brand can retain its audience, provided a reasonable standard of quality is upheld throughout.

Video games had the double benefit of easing naturally into franchise models and being a new, upstart electronic medium in a position to technologically revolutionize itself every few years.¹⁴ Maybe I wouldn't have been completely hooked on video games until my late twenties if the 8-bit cartridge-based home console had remained the industry standard; there's only so much that can be done within the limitations of the format. But then came the 16-bit cartridge console, the 32-bit CD-ROM console, the 128-but DVD-ROM console, and so on, indefinitely. Growing out of something is a much simpler affair when it's not growing up with you. Final Fantasy was a revelation when I was seven years old. Final Fantasy VI was a revelation when I was eleven, Final Fantasy VII was a revelation when I was fourteen...

And then when JRPGs left me feeling cold, first-person and over-the-shoulder shooters suddenly became brilliant—Resident Evil 4, Half-Life 2, Portal, BioShock, Dead Space—and 2D fighters started gaining momentum again with King of Fighters XI, Rumble Fish 2, Street Fighter IV, BlazBlue...all living rent-free in my head (as the kids say) for years, and inviting their friends.

|

| (via Oatmeal Snowman) |

It must be borne in mind that these several consecutive decades of rapid improvements to commercial media were concurrent with several consecutive decades of capital accumulation and consolidation—the former being a concomitant effect of the latter. What all of this technical development represents is the unabated self-strengthening of the system of which the culture industry is an organ.

The social byproducts this system's dynamics are sometimes popularly called "neoliberalism"—referring to the dependent variable by the name of the independent, but never mind that. Neoliberalism is becoming a metonym for, among other things, the dissolution of all relations except for those entailed by contract and exchange on the free market, alienation from the labor one performs and the products one consumes, the undercutting of religious belief and metaphysical interest, and the incremental chipping away at civic engagement, communal ritual, and familiarity with the "natural" world. The last few items can are all direct consequences of electric media, of course, but we'd be foolish to think we can disjoin the PlayStation, the smartphone, or streaming video from capitalist social structures. We have downwardly mobile generations with an ingrained sense of powerlessness and isolation, whose jobs are meaningless to them, who don't have the support of social networks that were once built up through participation in local organizations (a church, a sports league, a volunteer group, etc.), who are keenly aware of their position on the outer circles of a highly centralized and venal gerontocracy, and who feel themselves unable to control, change, or take interest in a lifeworld that meets them as an indifferent or even adversarial alien manifold.

Should we wonder why the temporary escape hatch of electronic entertainment should bring such relief so as to seem liberating? Or that one would partially ground their identity in a media franchise and connect most effectively with others who do so as well? Or that they are apt to interpret events in their world by framing them in relation to media franchises, somewhat in the same way a nonliterate "primitive" would associate people, things, and events with episodes and aphorisms from oral narratives?

The internet has made possible a novel form of "empowerment" through the production of fan-content—often carried out for no monetary compensation, but reinforced by device-mediated social feedback and by the stimulation of the production process itself (i.e., the process of editing a YouTube video, mucking around in Photoshop, reading a paragraph of one's fanfiction back to oneself, etc.). This isn't as much a novel form of mythmaking as of myth manipulation, perhaps representing one of the parallels between tribal orality and electric nativity of which Dr. McLuhan made so much. The nonliterate person listened and later repeated what he remembered, perhaps adding or omitting details depending on his powers of recall and feedback from his audience. The avid consumer of fiction during the Victorian Age read novels, and perhaps referred to the text in any compositions they might write, but were strongly discouraged from plagiarism, or from "adopting" a published writer's scenario and characters.¹⁵ The avid viewer of Star Wars and Indiana Jones movies could, if he got a job in Hollywood, borrow from those movies, but had to do so discreetly if he didn't want to be branded as a hack; if he was an amateur, there was nothing stopping him from making embarrassing Star Wars and Indiana Jones fan-films that would only ever be watched by the people who helped him make it.

With all formats having merged into one, it has become possible to recut, redub, remix, mash up, hack, compile, reanimate, and disseminate—never exceeding or replacing the original object, but always reaffirming its significance and facilitating its circulation, even when the intent of the derived work is to mock it. YouTube would, of course, delete a hell of a lot more content if the property holders hadn't come to realize that a clip, a best-of compilation, or a reanimation are all arrows pointing back to the original product or franchise. In a way, this is something like a recapitulation of the folkloric tradition, insofar as it lets the common people have their fun and exercise their creative powers without threatening the position of the "official" mythmakers and the social structures in which they are comfortably situated. (Such practices often fortify those structures: the lore surrounding folk saints reinforces the spiritual authority of the church instead of challenging it.)

|

| Omfak (via Esh) |

In coming back around at last to The Faces of Evil and The Wand of Gamelon, all that remains to be touched on is the character of camp: the tragically ludicrous, the ludicrously tragic. I'll assume camp needs no explanation in 2022, so I'll hold back from block-quoting Susan Sontag. It will suffice to call attention to four points:

1.) Camp is only possible under modern conditions of production; it can't emerge as an aesthetic sensibility when cultural products aren't being dumped onto the market on a industrial scale and at an industrial pace.

2.) It cannot happen until there has been a general disintegration of communal bonds—which, so far as we know, is an invariable consequence of industrialization, so this follows from item 1.¹⁶

3.) Appreciation for this or that camp object, or a bundle of camp objects, is a shibboleth. Sontag, of course, alluded to the camp sensibility's social function as badge of membership in urban gay communities.

4.) When the internet opened up new venues for socializing (after a fashion), there were communities where citations of or references to certain exemplary pop cultural failures was likewise a signifier of deserved belonging.

Appreciation for digital grotesquerie isn't quite equivalent to the kind of camp which Sontag examined, and queer fans of John Waters movies might take exception to The Faces of Evil and The Wand of Gamelon being categorized as camp—but the difference is in the particulars, not the principle. Faces of Evil and Wand of Gamelon became beloved, in spite of their being ugly, unplayable garbage, because of the awkward and inept earnestness of their cutscenes. Being aware that the games existed at all was a sign of internet savvy; it meant that somebody spent time in corners of the web that most people didn't know or care about. MAH BOI memes and zeldakinglaughing.gifs became part of an exclusive group's shared language.

Maybe The Zelda Reanimated Collab qualifies as a form of digital folklore. Let's say that it does: it cites and augments a synthetic mythology fabricated and promulgated by the culture industry; the CDi Zelda games were part of the early-2000s internet's lore and lingo; the collab itself was a collective effort not unlike the erection of a Gothic cathedral (exponentially less grand though it may be). If it meets the criteria for a hermeneutical treatment, what meanings do you suppose we'd discover?

We won't go down that spiral here. The only point of this has been to contextualize this particular (and, in the big picture, insignificant) digital artifact in terms of the historical production, circulation, and functions of myth. But whatever it means can only be understood in terms of the cultural and material conditions that determined its production.

That'll be the subject of the next and last part of this little exercise. I promise it'll be short.

NEXT: はかなき夢

1. But what about Homer? The Iliad doesn't even take place in Greece, and the Odyssey tells us very little about the landscape of Ithaca (wherever it is) beyond basic features like a mountain of shimmering leaves and the fact of its "low-lying." There is an ongoing debate about the illiteracy of Homer (whoever he was/they were), and it must be taken into account that the storytellers of the dark age following the collapse of the Mycenean civilization would find a rapt audience for tales of the wars in which their ancestors fought.

2. cf. Harold Innis, Bias of Communication (1951)

3. cf. William Butler Yeats, The Celtic Twilight (1893–1902) and Zora Neale Hurston, Mules and Men (1935)

4. Marshall McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962)

5. H.J. Chaytor, From Script to Print (1945)

6. I'm loath to make sweeping statements about literary traditions in which I'm not very familiar, but my dabbling in Middle Eastern and East Asian literature during those regions' chirographic periods somewhat appear to conform to the pattern. The 1001 Nights (ca. 9th century?) clearly has roots in oral storytelling; three of the Four Novels of China are based in myth and history; and so on.

7. We could say the same thing about Greek and Roman poetry and drama. Athenian tragedy reenacted and elaborated on mythical figures and episodes with which people would have already been familiar; Ovid is most known for an epic concatenation of Greek myth, and Virgil spun a national founding myth from disconnected tales of Aeneas' travels after Troy's destruction. It's evidently an open question as to how much of the Aeneid's story was compiled from nonextant sources and how much was purely Virgil's invention. At any rate, antiquity's chirographic tale-tellers apparently weren't in the business of fabricating new characters and plots from scratch.

8. Marshall McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962)...again.

9. Harold Innis, Bias of Communication (1951)...again.

10-a. cf. Ferdinand Tönnies, Community and Civil Society, 1887

10-b. Mass media is a double-edged sword. In tribal societies, one has a choice between conformity or exile. The technological and social conditions that make it possible for the individual deviant or a subculture to exist safely in a society with which they are at variance are also responsible for the prevalence of loose, impersonal relations among the general population. The more permissible it is to go against the grain, the deeper and more pervasive the alienation in a society.

11. The Church of the Apostles itself is fictional, but Melville undoubtedly based it from personal observations of one or more Bohemian associations in mid-nineteenth-century Manhattan.

12. Not always, of course: the ancient Greeks and Romans had no priest castes.

13. Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947)

14. Not to mention their potential to be a more effective Skinner Box than television executives and advertisers could have ever dreamed.

15. The novel came of age with capitalism, and practices surrounding it evince respect for liberal strictures on intellectual property.

16. Beyond the aesthetic differences, how much separates the camp connoisseur from the protagonist of À rebours?

No comments:

Post a Comment