The notes about archetypal shadowplay alluded to at the end of the last post ended up becoming a separate thing, which you can read

here. I'm still not sure how much sense it makes. At some point I ought to try systematizing this shit.

We've passed the halfway point, and my plan was a total success. I can't tell you how much I want to write about anything other than Magic: The Gathering at this point. Let's hope I think back on this the next time I think that a long-longform thing about some pop-cultural this or that would be an easy and fun thing to do.

___________

Here we are at the Otaria Saga! This one is...this one's weird.

To recap: Dominaria withstood the Phyrexian invasion, but much the worse for wear. Civilization lies in ruins. Urza (Magic's original central character) and Gerrard (hero of the ill-starred and awkwardly executed Weatherlight storyline) both gave their lives to destroy Yawgmoth once and for all. Phyrexia has been blown to smithereens. The drama's done, but the game continues. As long as the addicts fans are buying the goods, production cannot cease. Wizards of the Coast had a release schedule to observe.

This is to say that the creative team at Magic: The Gathering R&D had to figure out where the story should go next. The answer: Otaria.

I'll preface this by citing and concurring with

Multiverse in Review's opinion that there was some behind-the-scenes turmoil at Wizards around this time, which probably began much earlier—possibly during the abrupt change in direction that ushered in the

read the books era of Magic lore:

We should remember that way back in The Duelist #33, which came out when Urza's Saga was current, we got our first admission that the Weatherlight crew had hogged the spotlight too much and that WotC was going to showcase less of the story in the cards. And Nemesis and Invasion already had spelling inconsistencies in the names of characters between book and cards. Minor issues on their own, but in light of what came later it is tempting to see this as the precursors of Odyssey block's naming inconsistencies and the complete card/story split in Onslaught block. Especially since Rei Nakazawa cited the spotlight-hogging nature of the Weatherlight crew as a reason for this new creative direction.

So I do think this larger conjuncture of declining quality set in during the Weatherlight Saga, although I can't quite figure out what was cause and what was effect. Were things already bad but was this hidden from us simply because we tend to think of the Weatherlight Saga as one concrete whole and the Otaria Saga as another? Had people at WotC wanted to ditch the original creative direction sooner, but were they unable to do so until the Weatherlight Saga had wrapped up? We also shouldn't forget that the middle parts of the Weatherlight Saga came out during the combo winter and the following exodus of players during Masques block, the time Magic came the closest to dying. I imagine that after R&D had been chewed out over that all available resources were being poured into reviving the cardgame, rather than into the storyline.

Last time, we didn't dwell for long on how Apocalypse, the third and final set of the Invasion block, seemed to have lost both the plot and interest in itself—but the decline in creative quality from Invasion to Apocalypse is jarringly apparent when the two are juxtaposed. Multiverse in Review also points out that the entire creative team was fired not long afterward. Something was up, but it's impossible to know exactly what. Wizards has always been pretty good at keeping its internal drama under wraps.

I'm inclined to believe that worldbuilding and lore were indeed left to simmer on the backburner while the problems that plagued the game were being addressed. It makes sense: it doesn't matter how fascinating the story is or how pretty the cards look if playing with them is so boring and/or frustrating that people lose interest in allocating a portion of their income to booster packs. Even though I was introduced to the Odyssey and Onslaught blocks years afterward, when I was sifting through my friend Jason's collection to build my first EDH deck, I always felt there was something off about them. As game cards, they're serviceable, and occasionally excellent (there is no word for the sphincter-clenching emotion experienced by a lapsed monoblack enthusiast during the moment he discovers the existence of Cabal Coffers), so mission accomplished—but I remember asking Jason what exactly the conceit of these sets was supposed to be. Because I remembered each Magic set having a distinct identity back when I played. Ice Age and Mirage were both pretty obvious. Fallen Empires and Alliances, ditto. When I found cards from Time Spiral, Lorwyn, Zendikar, etc. in Jason's collection, I could usually infer those sets' overall vibe before too long.

But I couldn't for the life of me discern any preeminent motifs in the Odyssey and Onslaught cards. I don't think Jason was able to give much of an answer, either.

Let's get to the meat of the tomato, as

Clay Pigeon says. The first half of the Otaria Saga consists of

Odyssey (October 2001),

Torment (February 2002), and

Judgment (May 2002).

Having somehow escaped the worst of the Phyrexian invasion, the continent of Otaria outpaced the rest of Dominaria in rebuilding something resembling a civilization, and became a haven for refugees from across the world. A century after the ashes settled, the center of power in Otaria lies in Cabal City, controlled by a consortium that's part mafia and part death cult, and which presides over an economy that's evidently based on arena combat.

Very Beyond Thunderdome; fitting for a scenario that literally takes place after [the] Apocalypse.

And, uh, there are human and aven nomads on the plains. A civilization of squid people lives off the Otarian coasts. Dwarves and barbarian tribes live in the mountains, and centaurs and bug people called Nantuko dwell in the forests. They're all up to something, surely. You can find out by consulting the wiki or

reading the books, but the cards themselves don't give us much to work with. I can't find the source now, but I read somewhere that the task of writing all of Odyssey's flavor text was dumped on a

single person who already had a heap of other responsibilities on his plate. He didn't botch it by any means, but it seems fairly obvious to me that his main inspiration was a looming deadline.

You'll remember that Mirage/Visions didn't work especially hard to encode an atlas of Jamuraa's nations, landscape, political conflicts, etc. in the flavor text of its cards, but that almost seemed beside the point when the stylized art and the snippets of local lore, poetry, and idioms so lavishly defined its world. The Odyssey block, on the other hand, seems unwilling to commit to any particular concept or tone. The art department is still deep in the funk that began during the Masques block, and the buttoned-down house style doesn't put in any work to help distinguish the scene on Otaria from that of any other generic North American fantasy property. The post-apocalyptic angle isn't leaned into. The inversion of the usual "white-aligned faction rules the land, black-aligned faction roils at the margins," isn't at all apparent unless you look at the promotional material or read the books. The substitution of Magic's usual color-aligned tribes (merfolk, goblins, and elves) with a plethora of new critters probably seemed like a significant move at the time, but...hmm. Incidentally, the Odyssey block was rolled out around the same time Metal Slug 4 hit arcades. Remember Metal Slug 4? Remember the impact it made by replacing Tarma and Eri with Trevor and Nadia? Well, me neither.

In all fairness: we might say that the new "graveyard matters" mechanics and the unprecedented preference given to black cards in Torment uses the game's mechanics to reinforce the scene—a land ruled by a death cult, etc.—but the fact I feel like I have to qualify the statement with "might" should indicate how well it gelled.

Now that I look again, I think part of the issue might be that little of the flavor text is ascribed to any particular speaker. Fallen Empires and Homelands, two of the weakest sets of all time, hit a pair of worldbuilding home runs by putting such care into the lore they delivered through the italicized text at the bottom of the cards. Fallen Empires used a fictional historical tome to give a scholarly gloss to the societies of Sarpadia and their respective collapses, while Homelands consistently let Ulgrotha's natives speak for themselves. Throughout the Otaria sets, most of the flavor text consists of unattributed quips. Some are pretty good, but again, I get the sense that most were written out of obligation, while the stuff in Fallen Empires and Homelands came from people who were truly interested in telling a story.

The main plot revolves around an artifact called the Mirari, which is part crystal ball, part the One Ring, and part monkey's paw. Once it appears on Otaria, it arouses fascination and obsession in anyone who sees it, and it grants its owners' wishes in a way that usually ends up killing them and destroying everything around them. Everyone fights over the Mirari; it passes from hand to hand, nuking its owners and everything they hold dear, until one of the main characters deposits it in a remote wilderness where nobody can get their mitts on it. There it begins leeching spooky magic into the land.

That's the gist of it.

All of this is only

hinted at in the cards, and it frequently comes across as embedded advertising for the novels. ("Want to know why Chainer gave a pet monster to Laquatus, how Balthor died, or what the hell is depicted on

Kirtar's Wrath?

Read the books.") That leaves us with the world that's built in the cards themselves, and we've already gone over that. The Odyssey block contains nothing like the dialogues between Arcum Dagsson and Soldevi Relicbane in Ice Age/Alliances, or the Love Song of Night and Day in Mirage/Visions. The wacky psycho dementia wizard Braids isn't half as charming or memorable as the swaggering fire mage Jaya Ballard, and the Cabal Patriarch is a poor man's Lim-Dûl who dresses like Shinnok from Mortal Kombat. Of the new races, only the cephalids receive much characterization (they're a Romulan/Ferengi hybrid with tentacles); for the rest, substituting "woodland society of elves" with "woodland society of bugs" and calling it a day was deemed sufficient.

The Onslaught block, consisting of Onslaught (October 2002), Legions (February 2003), and Scourge (May 2003), is, according to Multiverse in Review, the point where Magic lore hit rock bottom. The excerpt above alluded to a "complete card/story" split, and I can't fault the description.

I seem to remember scrolling through the magiccards.info indices to get a wider view of the Odyssey sets and coming away with a somewhat better idea of what was supposed to be going on. But then I moved on to the Onslaught block and found myself understanding it less as I took more of it in. It's an amorphous, unintelligible blob.

After the Duelist went out of print in 1999, Wizards took to exclusively publishing story information on its website, accurately assuming there was a massive overlap between the population of geeks who hung out at gaming shops and the thirty-something percent of Americans who had home internet access. But when the Onslaught block came out,

Wizards became suddenly stingy with its online lore resources. So just bear in mind that the only backstory anyone got for this next batch came from a couple of short (

very short) promotional articles on the website.

The story thus far: Jeska, a character introduced in the Odyssey block, has somehow or other been transformed into an evil person named Phage, and she seems to work for the Cabal now. A Robert Smith-looking wizard named Ixidor made an angel named Akroma to kill her, and Akroma maybe isn't terribly nice, either. Apparently the Mirari has been mutating living things across Otaria from where it rests deep in the forest. The new "morph" ability might reflect this in the set's mechanics—since it's kind of sort of suggested that morphed creatures undergo a gestation period in a walking arachnoid-crustacean cocoon—although none of the flavor text says anything about it, Wizards' online literature said nothing about it, and it only appears in a couple of illustrations. But it must be important, since Onslaught's symbol is an icon of said cocoon. Right?

Hold on. What's that in the art for Ixidor, Reality Sculptor (above)? An arachnoid-crustacean cocoon! Did Ixidor make all these morphed creatures, then? Who knows!

Before we touch on the absolute insanity of the Onslaught block's story, let's at least give it credit for what it does well.

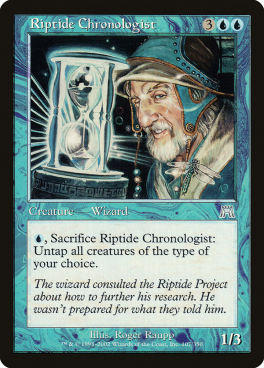

First: the Riptide Project subplot. The first set introduces the Riptide Project, a collaboration of humans and cephalids working in a research facility on an island off the Otarian coast. Their work seems to involve science and sorcery in equal measures, and a group of them has taken an interest in genetically reengineering a curious extinct species.

I feel like I would have been pretty excited (or worried) about this if I was still playing Magic in 2002. Nowhere in Onslaught does the word "sliver" appear, but the shape of the mold in Riptide Replicator doesn't leave much room for doubt.

Then, in Legions—Magic's one-and-only all-creatures set—we see the experiment has born fruit. Pointy, dangerously fecund, hive-minded fruit.

While the tumult involving Phage, Akroma, Ixidor, Kamahl, and the Mirari is happening on center stage, the second stage of the Onslaught block features the Magic: The Gathering reenactment of Jurassic Park. I guess the reintroduction of slivers to the game (they hadn't appeared since the Tempest block) couldn't be accomplished without a suitable plot contrivance, which made it necessary to ensure that somebody opening his first booster packs could be quickly apprised of their appearance on Dominaria and how it happened.

Second: the mutations. Notwithstanding the cocoons with many feet and wherever they came from, the Mirari is definitely having a strange effect on Otaria's populace.

From Onslaught to Legions to Scourge, virtually every humanoid depicted in the art becomes increasingly monstrous. The wizards become gelatinous oozes. Soldiers' faces close up and their bodies fuse with their armor. The Cabal clerics become slathering ghouls. Elves (I guess they arrived on Otaria between sets?) take on plantlike characteristics. I think what I found so puzzling about this is that the flavor text says virtually nothing about it. We're told in Onslaught that the animals in the Krosan forest (where the Mirari was secreted away) have been growing huge. A cycle of particularly strange-looking humanoids in Legions refers to the Mirari, too—but that's about the extent of it. Everyone's apparently a mutant by the time we get to Scourge, and none of them have anything to say about it.

Now that I'm looking these over again—I kind of love it.

Ever since the Mirari appeared and shit started getting blown up everywhere, life on Otaria has become hectic, and I like the implication that everyone's so inured to it all that they've adopted a resigned, blasé attitude toward their horrible deformities. "Yeah, I've got bony spikes growing out of my head and tongue, but what're you gonna do? The Jenkins kid down the street looks like the inside of a lava lamp, so I'm counting my blessings. You catch yesterday's pit fight?"

But it would be nice if Scourge, the Otaria Saga's finale, gave any indication as to what the hell is happening on Otaria. I genuinely find Scourge fascinating because it must represent some sort of abdication on the part of the creative department. Not only did they phone in it, it almost seems like they washed their hands of it altogether. They came up with adequate names for the cards (which is probably a more labor intensive part of the job than anyone suspects), communicated with the art department to give some sort of guidance regarding how the set's one important debut character and the mutated humanoids should look, and penned flavor text that's more or less appropriate to the cards it appears on—but there's no reference to the broader narrative in which it stands as chapter six of six.

Akroma and Phage are both gone; where did they go? The arrival of a godlike being called Karona must be important, because she gets a legendary card, has a couple

other cards named for her, and looms as a shadow in the five-color "

Decree" cycle—but Legions gives more information about its sliver subplot than Scourge gives about Karona. The set's emblem is a dragon, and there are a lot of dragon cards—or cards with "dragon" in their names, anyway—so dragons must be important here. So then why isn't anyone talking about dragons? Is Otaria being invaded by dragons? Is Karona fighting the dragons? Whatever happened to the Cabal Patriarch, anyhow? The card Upwelling (above) refers to Kamahl recovering the Mirari. Why? What does he do with it? And why hasn't

he turned into a hideous mutant?

Not that you'd know it from reading the cards, but Phage merges with both the angel Akroma and some woman named Zagorka (who only appears in the books) to become the (false) goddess Karona. And that's...well, that's all I got.

Multiverse in Review calls the Scourge novel a strong contender for the worst Magic book ever published. That's bad enough—and we'll get into that in a sec. But the bigger problem is that the people designing the cards (and all the pictures and words on them) and the person writing the books were working more or less independently of each other. That tracks: the narrative elements of the Onslaught block, such as they are, seem almost deliberately nondescriptive, as though the creative team was trying to minimize the risk of stepping on the author's toes. Conversely, the cards could treat the Riptide Project's blunder with the slivers in relatively extensive detail, since the books don't touch on those events whatsoever—the same way several important characters in the books fail to make it into the cards, or how the flavor text says nothing about to who Karona is, what she wants, or what she does, or what (if anything) she has to do with the Mirari, which may or may not still be the plot's MacGuffin.

The Mirari mutant-people aren't addressed in either the cards or the book.

This summary of the Scourge novel, written by the good people at

Hipsters of the Coast, is worth quoting in full, since there's no other way of getting across how deliriously bonkers the plot is:

The Mirari is a probe sent to Dominaria by Karn to monitor things but it has a flaw which is why everyone covets it and uses it to wreak havoc so instead of fixing things Karn just ignores it while Kamahl finally comes into possession of the Mirari and uses it to kill his sister Jeska who had a nascent planeswalker spark but Jeska gets reanimated by Braids to unknowingly be Phage who will become the mother of the reborn sorcerer Kuberr who has been dead for 20,000 years and during that time secretly created and manipulated the Cabal in order to facilitate his rebirth alongside his brother Lowallyn who was also dead for 20,000 years but could reanimate as a crazy person and thus was reborn as Ixidor and their third brother Averru who exists as a city.

Deep breath...

The three brothers are reborn and their mothers go to war with each other but Kamahl puts an end to it when he kills Zagorka, Akroma, and Phage in one fell swoop but instead of killing them it for some unknown reason turns them into Karona who is the manifestation of all magic on Dominaria and is now in control of Jeska’s body but the three brothers have plans to kill Karona and steal her power which is what got them killed 20,000 years ago in the first place but here we are repeating the sins of the past.

One more deep breath...

So finally Karn visits Kamahl and decides it’s time to set things right but instead of calling himself Karn he calls himself Lord Macht because J. Robert King has a hard-on for cheesy plot revelations but either way he tells Kamahl how to use the Mirari to destroy Karona and that by doing so it will restore magic to Dominaria so Kamahl and the three brothers battle Karona who kills the three brothers and then breaks all of Kamahl’s fingers so he can’t wield the sword but then her two prophets kill her when her back is turned because Karn told them to and then everything goes back to normal and Karn takes Jeska away to his new metal plane of Argentum where he restores her and informs her that she’s a planeswalker.

This block of text makes only slightly more sense to me than it probably does to you. The "three brothers" don't appear at all in the cards. (Well, Ixidor does, but there's no mention of him being anyone's brother.) Neither does Zagorka, nor do Karona's prophets. There is no legendary land card called "Averru." There's no indication given anywhere that Karona is the result of some sort of necromantic fusion dance, or that the plot was resolved by a literal deus ex machina via the arrival of Karn.

Oh, you didn't know that the silver golem Karn became a planeswalker after Urza and Gerrard blew themselves up to destroy Yawgmoth? Sounds like somebody wasn't reading the books during the Invasion block.

For an alternative gloss, we turn to Killing a Goldfish's series of Magic reviews (now defunct), which analyzes each block from a mechanical perspective—something I'm not well equipped to cover, since poring over an index of old cards and occasionally encountering them in EDH is

very different from having firsthand experience of their contemporaneous metagame. Mr. Goldfish was there for Scourge, and I'm willing to take him at his word

when he says its mechanics make as much sense as its lore:

Here is the true story of Scourge: the dictate was given that it would be about Dragons, because Dragons are a creature type, and people like Dragons. It was also decided that it would get a keyword, and a non-keyword subtheme that fit into the above. Unfortunately, the development team was replaced by 1920s German Dadaists, who attempted to destroy culture through the lens of Magic cards.

You want Dragons? You will have four of them. We will use the word “dragon” in other unrelated cards. Your bourgeois ideals cannot stand up to the absurdity of life. Your attempts at constructing meaning are a child shouting into their porridge. We will create a poetry of our mechanic, by opening the dictionary and assigning a word to a concept that directly contradicts the dragon you hold so dear. You wish for a tournament-playable Dragon? We oblige with a white creature that gives you a Plains for seven mana a turn, payable in installments. You cannot win. Bladewing, Mind’s Desire, dada m’dada dada mhm, dada 7U 1/1. Of the parts of the “dragon,” we have decided to reference its converted mana cost. You care about flying, and other insignificant things. You will care about a large number placed in a place you’d rather it not be. Dada is life. What is a dragon? A dragon is a word. It is not real, but nothing is, and words are things, and dada is real.

...I don't know about you, but I think it's time we got the hell out of Otaria.

Multiverse in Review posits that the Onslaught block's story might have been allowed to go so completely off the rails at the end because the creative department was already pouring its energies into the

next set, and was satisfied to let novelist Robert J. King wrap things up however the fuck he liked. I'm ready to believe it, because the Mirrodin block evinces an enthusiasm for worldbuilding that the game hadn't seen since Mirage. Seven years.

An artifact-heavy set was nothing new to Magic. The very second expansion, 1994's Antiquities, was designed as a means for players to inject more artifact cards into their decks. Mirrodin (October 2003), Darksteel (February 2004), and Fifth Dawn (June 2004), place an even heavier emphasis on artifacts, and make the lore that Antiquities introduced as an aesthetic complement to its emphasis on a particular card type seem woefully lacking in imagination.

An artifact-themed set about a war waged between rival artificers? How droll—Mirrodin, the new artifact-themed expansion, is literally the Planet of the Artifacts.

Mirrodin was a game changer. Among its other innovations, it gave us equipment cards and the "indestructible" attribute. It inaugurated the "planeshopping era," where the game's ever-growing mythos finally expanded beyond the confines of Dominaria. And, as we mentioned above, it was the first time since Antiquities (fittingly enough) where the mythos and aesthetic were determined by the game cards' functionality qua game cards.

To my reckoning, Fallen Empires and Ice Age register the period where the people designing these collectible game cards perfected the improvised method of storytelling first seen in Antiquities: draft a comprehensive atlas of a fantasy setting during a certain period of that world's history, with all its important regions, peoples, institutions, conflicts, influential figures, etc., translate as much of it as possible into the names, illustrations, and flavor text on the cards, and let the players immerse themselves and discover more about that world as they grow their collections.

But after Antiquities, it wasn't until Mirrodin that another set whose narrative and aesthetic aspects weren't only decided by and "native" to the basic format of a collectible card game, but by the specific mechanics of that card game—of Magic: The Gathering. It would theoretically be possible to transplant all of the cosmetic attributes of the Tempest block (maybe changing a few names) into some other late-1990s CCG and not lose anything of fundamental importance in the expatriation. Same goes for the Otaria blocks.

Mirrodin, however, couldn't be anything but a Magic: The Gathering world and story because of the meaning that crystallized around the word "artifact." Mirrodin isn't simply a metal world; it's an artifact world, and there's no other context where "artifact" has precisely the shade of meaning as it does in Magic. Every idea that was written on the creative team's whiteboard in their brainstorming sessions followed from the "Planet of the Artifacts" conceit.

Incidentally, so did the choice of reprints from previous sets:

Notwithstanding R&D's renewed zest for worldbuilding, we're still deep in the read the books era of Magic lore. This means that Wizards had a financial stake in not allowing the Mirrodin block to divulge its own story—or at least, not the part of it where a protagonist goes on a journey, makes friends, overcomes obstacles, confronts a villain, etc.

That hero is an elf named Glissa Sunseeker, and if the cards are to be trusted, she's on a journey to discover The Secret at the heart of Mirrodin. (Although in the novels, she's really on a quest for revenge—oops.) The villain is one Memnarch, who...hmm. It's complicated.

So: the silver golem Karn, now a planeswalker, created Mirrodin the same way Serra created her own empyrean node in the multiverse. Like most gods or godlike entities, Karn fashioned his world and its people in his own image: a metal sphere populated by golems. The golem called Memnarch was created to mind the store while Karn went galivanting about the multiverse. As time passed, the planet's core ejected four orbs of raw mana, circling the world as "suns." At some point, Memnarch went nuts, killed off the ur-golems, and began populating Mirrodin with lifeforms abducted from other planes as part of a massive, centuries-long science experiment (and a continuity nightmare for Magic lore chronologists). Mirrodin's geography evolved from a perfect, featureless sphere to a heterogenous landscape; the biology of its organic inhabitants became partly metal; the metal forms of its artifact-creature inhabitants became partly flesh.

Oh, you want to know how and why? Read the books. Or maybe not: if Multiverse in Review can be trusted, the Mirrodin trilogy is pretty mediocre.

Did I mention that Memnarch is the Mirari from the Otaria Saga? Karn took it to Mirrodin and remade it into a golem. It's one of those things that's probably best not to think too much about, especially since it's irrelevant to the story—though it suggests to me that the creative team either wasn't looking at the big picture, or they otherwise thought it would be poignant and/or hilarious to characterize Karn as the most inept god-playing planeswalker in the whole Magic mythos. This is two worlds he's already fucked up.

"There's a secret at the heart of this world," says Glissa, "and you have to buy three novels to find out what it is."

"Each is written by a different author," Glissa adds, "and we hope that none of you are sufficiently literate to regard this as a red flag."

I think the secret is supposed to be that Mirrodin's population is descended from random people from random worlds whom Memnarch fished from the multiverse using his patented "soul traps." Or it might be the existence of the mycosynth, a fungoid organism growing in Mirrodin's hollow core, whose spores somehow transmute flesh into metal and metal into flesh. Or it might be that Memnarch first began going nuts when he came into contact with a stray drop of some strange oil that appears at the very beginning of the first novel and is never referred to again.

Hey! No reading ahead. Not cool.

I mean the oil isn't referred anywhere in the Mirrodin block. The mycosynth appears in a couple of cards (Mycosynth Lattice, above, and Mycosynth Golem), but there's no indication that the stuff is important, let alone the reason why everyone on Mirrodin is partly metal, partly real flesh. The fact that Mirrodin's peoples are the product of a sinister multiversal human[oid] trafficking scheme is alluded to in the first set, but it's dropped pretty quickly, and the phrase "soul traps" has never been printed on any Magic card.

Still, in terms of how Mirrodin develops and delivers its lore, we're looking at a tremendous improvement. Now that the potentially ruinous double blunder of the Urza and Masques blocks was in the rear mirror, the decision-makers at Wizards were apparently comfortable with allocating more resources and talent to the game's cosmetic aspect, and the creative team brought more vim and verve to the task of constructing a mythos for the new set than anyone had seen in years. This was the first time since Masques that they had a chance to develop an entirely new setting, and they wanted to do it right. So they took a cue from the pre-Weatherlight sets and returned to the "panoramic atlas" approach that worked so well in sets like Fallen Empires, Ice Age, etc.

Color-aligned factions have been a part of Magic since Antiquities. Linking each "tribe" to a geographical location tentatively began with Fallen Empires' giving each of Sarpadia's collapsed societies a pair of nonbasic lands representing their domains, but little attention was given to the ecological particulars of any setting and their role in shaping the cultures and critters represented in the cards.

To its credit, the Otaria Saga—at least on the drawing board—took the continent's geography into account, but the relation between the color factions and their respective stomping grounds was determined by rote procedure. "Okay, white cards are human nomads and bird people, so we need a prairie to drop them on. Green cards are bugs and centaurs, so we need to think of another name for another forested region. Black cards are clerics and the servitors of a necromancer mafia, so let's give them a city. What? Swamps? Okay, fine, maybe there's some swamps around that city. Who cares?"

I would be surprised if Mirrodin's creative team didn't start with the landscape. Committing to the "Planet of the Artifacts" conceit meant foregoing any possibility of writing "forest" on the whiteboard and drawing a line connecting it to the word "elves." A forest? On a planet made of metal? How does that work? It doesn't even have dirt. How would trees grow?

The same question applies to all of the other basic land types relating to each faction: plains, swamps, mountains, and islands/seas.

As the story goes, Mirrodin was a featureless metal sphere when Karn left Memnarch in charge. After his sanity started slipping and he decided to bring organic life to the plane, Memnarch began converting it into a massive terrarium with artificial habitats where his "guests" could reside.

Mirrodin's "woodland" region, called the Tangle, is defined by dendritic copper stalagmites caked in verdigris, laced with a ravel of vine-like cables. (Some of the "trees" produce an edible substance called "gelfruit;" an effect of the mycosynth?) The inhabited areas of its "plains" are the Razor Fields, marked by literal blades of "grass" that offer a natural defense for the region's sapient peoples and prey species. The Mephidross ('mephitic" + "dross"), the Mirran version of swampland, is suffused with polluted water, sludge, and a toxic effluence called necrogen that erases memories, deforms living matter, and mutates its victims into nim (the Mirran strain of zombie). The Oxidda mountain chain is a gigantic complex of protuberant iron structures, powerfully magnetized, situated on top of a gigantic self-maintaining smelting furnace.

Mirrodin's ocean, the Quicksilver Sea, deserves special mention. A vast expanse of liquid mercury doesn't make a convincing home for the merfolk, sea serpents, cephalopods, etc. usually associated with blue cards, so Magic R&D had to figure something else out. So it invented a new race called the Vedalken—four-armed, blue-skinned, control-freak brainiacs—and set them up in a network of interconnected "spires" rising over the ocean's opaque surface.

This solution to a problem posed by the new setting shows the creative team's commitment to following the internal logic of Mirrodin's central conceit. Though blue part of Mirrodin deviates more from the norm, its other color factions are no less different in having been determined by the environmental peculiarities of Memnarch's terrarium. Clearly a lot of consideration was given to how the folkways and social structures of Mirrodin's various tribes (and the habits of the local wildlife) are contingent on which artificial habitat their ancestors settled down in. I appreciate ecological thinking, even when it's performed for the sake of decorating a collectible card game.

I don't want to oversell it and say that it's a work of epochal brilliance, but more thought and effort went into constructing Mirrodin and its peoples than any Magic setting since...well, I'm tempted to say ever, since the designers had no preexisting template for an "artifact world" setting. All they could do was ponder the features of the environment, the dictates of each color's "philosophy," and try to figure out what kind of societies would emerge from the dialectic. The result is one the most superbly realized worlds in the Magic multiverse, and certainly its most alien.

Side note: Mirrodin's design succeeded in spite of a

major handicap. We're smack dab in the middle of the reign of

fascist art director Jeremy Cranford, who famously insisted that Rebecca Guay's art was too "feminine" for the visual

bland brand identity he envisioned for Magic. The fact that Mirrodin manages to be interesting on the whole in spite of Cranford's strict enforcement of a standardized, unimaginative house style speaks to how much heavy lifting was performed by its the non-pictorial components. (Seriously, though: imagine what a

trip Mirrodin would have been had Sue Ann Harkey overseen its artwork.)

Repetition and permutation is the life of myth, and Mirrodin exploits it to great effect. The block is packed with five-card cycles that emphasize and reemphasize the interrelatedness of world's ecology and its culture. The "beacon" cycle shows where the Mirran suns/moons were ejected from the core, and hint at the rituals surrounding the annual flare-ups at the "lacunae;" the

"shard" cycle and mana-producing Myr creatures peer into the worldview of the Mirran races; a pair of color-aligned golem cycles characterize the five major ecotypes; and so on. Taken individually, none of the cycles are terribly evocative, but the combinatorial effect is almost hypnotic.

It's a simple device—repetition and modification—but it exploits the attributes of the format. The more the collector buys packs and sifts through the cards, the more he sees a body of relations reiterated and rearranged, the more significance it all accrues, impressing itself in his memory and emphasizing the variations in the theme.

I wonder if, at the time, Mirrodin was the breath of fresh air that it seems to be in retrospect. Trying to write about Magic lore and its approach to building its mythos has honestly been a slog since Weatherlight. There's not much to do but try to summarize this or that plot, since the poor reception of the Gerrard & Friends Show prompted Wizards to put the creative department in a straightjacket and forbid them from further experimentation. Half a decade later, they remembered that this design space can actually be used to do something kind of interesting, and began playing around with it again.

Let's see how long it lasts.

Killing a Goldfish guy truly captures the essence of Scourge as a set of cards and mechanics.

ReplyDeleteSomething else that goes into making Odyssey what it is - Maro designed the set with the express purpose of subverting as many expectations as he felt he could get away with for a Magic set. This is why all the until-this-point established tribes went away, this is why the set mechanically revolves around throwing away your hand as fast as possible, and why there's a bunch of murderous squirrels about.

From the perspective of someone with a finger on the pulse of Standard at the time, Mirrodin wrecked the game again. Something like nine cards got axed from the format, at a time when Wizards did not take Standard bans lightly. Don't recall people being super thrilled with the block.

DeleteI hear the draft environment was good though!

As a little trivia kuberr is supposed to be this scion of darkness guy https://scryfall.com/card/arc/23/scion-of-darkness good luck figuring it out.

ReplyDeleteI do remember starting to play mtg around the Odyssey - onslaught times and the split between the story and the cards was so big that I for one thought they were not even trying to say any kind of storyline with the cards, only using them to flesh the setting and show some of the characters.

Maybe it is simply nostalgia but I do have a soft spot for otaria and it's peoples. The beaten up always stretched order that basically survives on faith and teamwork. The cool guy cabal that has all the money, all the zombies, all the nightmares and all those cool looking bald cleric ladies. I always had a good chuckle with the Florida man-esque disregard for life and sanity present in most of the barbarian cards. Also loved all of those nonsensical cuasi zen nantuko teachings (we need more insect people in fantasy) and I love with all my heart the power hungry mind stealing surface flooding cephalids.

That said I never had any love for mirrodin. I usually attribute it to all the art looking samey and not quite fantastical on its own. Besides, I knew Kamalh and chainer, even if only as a quick beater and a slow recycler of death creatures, and even then they had desires and dreams reflected in the cards. But I don't remember seeing any of the legends of mirrodin in the card until years later when I started playing commander with the friends of my elder brother. On the other hand I do remember being blown out of my mind when fifth dawn came out and now the plane had five suns, that's the magic of having 10 years I guess.

Also I do appreciate all the work you take for these articles. Sorry you have to smoke the whole package but at least we are past the halfway point.

TCP

ReplyDeleteWell I managed to screw this comment up somewhat. I only wanted to reflect on Mirrodin being the first set I ever drafted, making it my gateway into "serious" Magic.

DeleteBefore Mirrodin, my Magic playing consisted mostly of fighting against Legion-era Sliver decks in the high school stairwell (and eventually giving up and joining the Sliver army myself). By the time Mirrodin came out I had enough experience that I finally felt confident walking into the local shop and signing up for a draft. And, indeed, I beat the shop owner in the finals and won the first draft I ever participated in (thank you, Skyhunter Cub!). I only drafted a few times after that (both for Darksteel I think) and now that I have more friends who are highly-competent at drafting I've realized how out of shape I really am, but that first drafting experience really was something special.

One last anecdote -- when Mirrodin spoilers came out my friends and I were shocked at the high power level of the cards. Nowadays, having played enough EDH to sweat any appearance of Lightning Greaves, Swords of X and Y or a well-utilized Skullclamp, I can say that our judgment was accurate.