Psst. I'm still over on Substack, but I did say this would be my receptacle for whatever dragged-out, uncritical pop culture writeups I might feel irresistibly compelled to throw together. I'm afraid the time has come to use it in that capacity.

A more subtle and intractable problem is that superhero comics are suffering from ossification. For the most part it's only the eminently recognizable legacy properties that sell copies these days—brand new titles featuring brand new characters seldom last long—and most of their serials have been published more or less continuously for upwards of fifty years. Maybe they haven't completely exhausted their possibilities, but a whole lot of them are stuck remixing their greatest hits for all time. Gotham City burns to the ground, the Joker executes his ghastliest scheme ever, and a dear ally of Batman's pays the ultimate price—again and again and again. Gotham is rebuilt in a month, Joker escapes, and Robin comes back to life after a few years. Tony Stark disgraces himself and loses it all, redeems himself and claws his way back to the top, disgraces himself and loses it all, redeems himself and claws his way back to the top, ad infinitum. Wally West replaces Barry Allen as the Flash. Then Barry Allen replaces Wally West as the Flash. Then Wally West replaces Barry Allen as the Flash again. Magneto switches sides, becoming a hero, then a villain, then a hero, then a villain, then a hero, then a villain, then a hero again. Marvel stages another Civil War, Secret War, and/or Secret Invasion. The DC Universe is rocked by Crisis after Crisis, each purportedly a million billion times more epic and threatening than the last. Everything changes and then nothing changes, and there's no destination, no possibility of a final resolution. Just the occasional universal reboot or reunion of heroes that sets everything back to square one so the books can tell the same stories about the same people, only a little different. "Comics are essentially trapped in a perpetual second act," writes one Darren Mooney, "a story without an ending."

HONORABLE MENTION: ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM:

HOUSE OF X / POWERS OF X (Jonathan Hickman, 2019)

Not an honorable mention so much as a handicap. "Hoxpox" was the best series of the Krakoa era, bar none. It's really no contest, and it's a damn shame that the series that inaugurated a new beginning for the long-anemic and editorially hamstrung X-Men franchise should have been superior to everything that came afterwards. The Krakoa experiment peaked as soon as it began.

That was probably how it was bound to play out, unless the Marvel editors and the writers of the several relaunched X-books had been willing to give Hickman absolute control of the franchise, letting him preside over his colleagues like a dictator instead of a showrunner. The rumors say that Hickman left because he had a story he wanted to expedite, but the other writers got their way in demanding more time and latitude to explore the implications and possibilities of the new status quo. But who can blame them? Compared to Hickman's reorientation of the franchise, Grant Morrison's decade-defining paradigm shift back in 2001 seems like a timid pivot. House of X/Powers of X changed everything about the X-Men, past, present, and future. I was skeptical of the promotional hype at first—and then Hickman had picking my jaw off the floor after every issue and counting the days till the next installment. House of X/Powers of X was brilliant. When the brand-new X-books to follow on its heels were announced, I knew I was buying their first issues. All of them. I wanted nothing more than to open my wallet and throw money at Marvel to signal how much I wanted this thing to keep going.

Notwithstanding the mindbending retcon involving Moira MacTaggert/Kinross, the unification of mutantkind, or the resurrection protocols, the boldest aspect of Krakoa's introduction was its moral ambivalence. Hickman wasn't the first X-Men writer to approach the mutant ethnostate angle, but nobody had done it like this. Professor X puts to rest his old dream of peacefully integrating Homo superior with Homo sapiens, and begins to guide mutantkind towards eventual world domination. He collaborates with Magneto, Apocalypse, and Sinister to build a mutants-only utopia, and upon the founding of the new nation he psychically declares to the world that mutants are the inevitable inheritors of the Earth. Leveraging its fantastic biotechnology, hardball diplomacy, and covert operatives, Krakoa soon becomes a power player on the global stage.

The long-time X-Men fan couldn't but have mixed feelings about all this, and that was the whole point. With the foundation of Krakoa, mutants were no longer the Marvel Universe's perennial victims, but a unified people and an upstart nation state with a manifest destiny ethos. To borrow an oft-quoted line from Steward Brand, Xavier and friends finally accepted that they are as gods, and they set about getting good at it. Hickman wanted to embrace the contradictions of the premise: what does it mean when Marvel's merry mutants give up on trying to be a model minority and embrace the connotations of the Linnaean name Homo superior?

I don't want to turn this into a whingefest, so it will suffice to say that a huge problem of the Krakoa era was that few of Hickman's colleagues were capable of approaching the scenario with the same degree of cerebral detachment and nuance, or were as comfortable with and capable of working with the ambiguities he set up at the experiment's inception. Another was the mass of ideas and themes Hickman introduced at the onset which other writers either dialed back or discarded altogether as time went on. By degrees Krakoa stopped being so astonishing, complicated, and creepy/beautiful, and slouched towards the mundane.

Then there's the inscrutable matter of editorial edicts. In House of X/Powers of X, Hickman was given carte blanche to do whatever he wanted, and I get the impression that the permission was gradually withdrawn. It wouldn't surprise me in the least if, some years down the road, it comes out that some of the more maladroit developments in the Krakoa saga were guided by Marvel's editors instead of the books' writers. Of course, since the Marvel Universe is an interconnected whole, it was probably impossible to go all-in on the Krakoa experiment without dropping the X-books in an alternate timeline or on a separate imprint, unattached to the mainline continuity. (This was perhaps why Hickman began his run with a built-in reset button in the form of Moira.)

At any rate—I guess we'll see where things go from here, but it's a hell of lot harder to be as excited about it as I was after reading House of X/Powers of X in 2019.

HONORABLE MENTION:

X-FORCE / WOLVERINE (Benjamin Percy, 2019– / 2020– )

#5

PLANET-SIZE X-MEN (Gerry Duggan, 2021)

I'd rather talk about what I liked about the Krakoa era than criticize what went wrong—but I have to say a few words about Gerry Duggan.

He strikes me as the kind of comic writer whom an editor appreciates on the basis that he's able to write multiple books, turn in work on time, get along with the artists, and promote the brand on social media. His ideas are decent, at least in synopsis, and he's certainly a better author than Chuck Austen. That's to say he's not a terrible writer, but he's most certainly a mediocre one.

He sorta tries to emulate Joss Whedon in writing quippy and smug dialogue, but interpersonal dynamics are apparently a foreign concept to him—which should really disqualify him from writing big-name titles with ensemble casts.* Oftentimes his stories feel like plot summaries with pictures attached to them. His comics have a conspicuously "woke" bent, which wouldn't be a problem if the tendentious insertions of his politics weren't so smarmy and obtuse—but this is really just a roundabout way of saying he's not a great writer. (You won't hear a peep of complaint from me about Vita Ayala's decidedly woke run on New Mutants. Ayala knows how to write a good comic book.) Duggan's Marauders was easily my least favorite of the inaugural "Dawn of X" titles. Off the top of my head, I can't recall a single damned thing that happened during his Cable series. If his post-Hickman run on the flagship X-Men book was ever worth buying and reading from month to month, it was mostly because of Pepe Laraz's gorgeous artwork.

* For comic book nerds, I propose an experiment similar to the one that Mike from Redletter Media performed in his now-ancient video review of The Phantom Menace. Make a list of the main characters of Duggan's X-Men and a list of the main characters of, say, Craig Kyle and Chris Yost's run on New X-Men: Academy X. Instead of jotting down adjectives describing each character's personality, take notes on how they relate to the other cast members. See how much less you write about Duggan's X-Men than Kyle and Yost's New X-Men.

And Duggan was the author to whom Hickman passed the baton on his way out. What can we call this but a mistake?

But I've got to give credit where it's due. Duggan's Planet-Size X-Men one-shot was the only event of the Krakoa era that came close to matching House of X/Powers of X in sheer audacity. I still have a hard time believing it was his idea and his book, and not Hickman's. To be fair, though, Planet-Size X-Men allows Duggan to play to his strengths while avoiding the areas in which he's lacking. It's all plot and spectacle. (Plus, Laraz is on pencils.)

The background: after the X of Swords crossover, Krakoa's lost half Arakko has been returned to Earth from the hellish world of Amenth. With it came some millions of mutants whose culture revolves around war and survival. They're not going to take orders from Krakoa's leaders, and definitely can't be expected to play nice with humanity when they get restless and wander off the island. Moreover, the living islands of Krakoa and Arakko themselves have become incompatible after being split apart and separated for however many thousands of years. These are pressing issues in need of a solution.

Not long afterwards, the Hellfire Trading Company (responsible for exporting Krakoa's miraculous biotech abroad) holds its first annual Hellfire Gala as a sort of Krakoan open house hosting the global elite.* We see snippets of the event in several different X-books, but there's a scene that's left mysterious. At one point in the evening, Emma Frost telepathically shows something to the attendees. "The fireworks," she calls them. The reader isn't privy to what happens—but judging from the guests' reactions, it's something huge.

* I know the Hellfire Club has a lot of history and clout in the Marvel Universe, but did Emma Frost ever consider that emblazoning the word HELLFIRE across Krakoa's public-facing institutions might make the world feel a mite justified in being jittery about the ambitious superpowered ethnostate?

The revelation arrives in Planet-Size X-Men. To make a long story short: the mutants terraformed Mars. In a single day.

A cadre of omegas from both Krakoa and Arakko restart Mars' geological processes, give it an ocean, an atmosphere, soil, and new floral, fauna, and microbial life. They raise a capital city and plop Arakko and all its inhabitants onto the Martian surface. Also: they declare that the planet isn't going to be called Mars anymore. Now it's Arakko. And it's the capital of the solar system now, the place where representatives from all the Marvel Universe's interstellar civilizations will come to do business. Earth has been reduced to a suburb.

It's hard not to appreciate why the international diplomats, notables, and Avengers attending the Gala were all seriously rattled, and whispering to each other about how to respond. This was Krakoa's biggest power play yet. The mutant ethnostate's founders (among whom are a guy who once killed thousands worldwide with an electromagnetic pulse, a former member of the despotic Phoenix Five, and a woman who made an assassination attempt on a United States senator and later murdered a presidential candidate) have already declared that mutants are destined to replace humanity, used unscrupulous means to secure diplomatic immunity for every Krakoan citizen in the nations importing their biotech, and made no secret of their disdain for baseline humans—and now mutantkind has its own planet one orbital zone out from Earth. After a flex like this, who could blame anyone for being terrified of Krakoa?

And afterwards, once he was instated as the X-books' "showrunner," Duggan started doing all he could to make Krakoa less ominous and ambiguous and more cuddly and altruistic and misunderstood. Feh. But let's take a moment to appreciate the rare occasion of a comic book event truly living up to its hype, and give Duggan the recognition he's owed for making it happen.

He still kind of sucks, though.

#4

X-MEN RED (Al Ewing, 2022– )

I considered giving this slot to Hickman's run on X-Men or to Kieron Gillen's Immortal X-Men. But since Hickman is more than sufficiently represented here already, and since Immortal X-Men is practically a vehicle for the big Events which Gillen spearheaded, I'm gonna go with Al Ewing's wonderfully solid X-Men Red.

A continuation of Ewing's S.W.O.R.D. miniseries, X-Men Red is about a group of Krakoan mutants and their business on Mars Arakko. Storm gets adjusted to her role as regent of the Sol System and navigates the fraught field of Arakki power politics. A disillusioned and disheartened Magneto, having left Krakoa and the Quiet Council behind, tries to put together a new life for himself on the red planet. Sunspot opens a bar and meddles in affairs of state. Abigail Brand's galaxy-wide machinations come to a head, and her S.W.O.R.D. subordinates counterscheme against her.

In this respect, X-Men Red follows after Hickman's X-Men in that it's all over the place. Beyond its "some X-Men do stuff on the terraformed and colonized Mars" premise, it's difficult to synopsize the book without going deep into the expository weeds. The weave of its plot is made even more convoluted by the fact that it was interrupted by a big linewide Event only a few months after it began, and then got involved in another just a few months later.

This was a problem it shared with Immortal X-Men and Si Spurrier's Legion of X, the other two X-books that debuted in the wake of Hickman's Inferno. First there was the A.X.E.: Judgment Day hullaballoo, and scarcely after the dust settled came Sins of Sinister, yet another alternate timeline hellhole story that swallowed up all three books for as many months, à la Age of Apocalypse. X-Men Red was best able to roll with the disruptions, since its loose plotting made it resilient against getting derailed. Immortal X-Men would have been tremendously improved if it had been allowed to actually stick to its premise of being a study of the individual members of the Quiet Council instead of spending half its run setting up and/or being wrapped up in A.X.E. and Sins of Sinister. Legion of X had the worst of it it, though: Spurrier was given neither the time nor space to find his footing and establish a compelling identity for his new book, which was canned after issue #10.But I've gone off track. There's a lot to like about X-Men Red, simply on the basis that Ewing knows how to write a bloody comic book. There's nary a wasted issue nor a fight sequence staged just for its own sake. Every scene builds towards something; every event has consequences for the bigger picture. After Hickman's text-only "data pages" became de riguer across the X-books, some writers struggled a bit with making them work. Ewing gets more mileage out of them than most of his peers, making them to do the sort of plot-related heavy lifting which would be cumbersome to cram into a pictorial sequence, and he manages to escape the snare of letting them come across as mere info dumps.

The two things about X-Men Read that I think deserve to be highlighted in particular are its "versus" events and its focus on Arakki culture.

Given its relatively short run (it's currently at issue #12, not counting the three issues of Storm and the Brotherhood that replaced it during Sins of Sinister), X-Men Red is perhaps disproportionately loaded with relatively quiet issues that just move the pieces around the board. When its main players finally collide and throw hands, always worth the wait. I could sit here and write out paragraphs explicating "Magneto vs. Tarn," "Sunspot vs. Isca," and "Storm vs. Vulcan," but it's usually as bootless to recount the grandiloquent passion of a comic book fight as it is to narrate the spectacle of a hyped-up and well-choreographed wrestling match. I'll just say that I love what Ewing has done with (or rather done to) Isca the Unbeaten, Apocalypse's ageless sister-in-law whose mutant power is to never lose at anything, ever. (One does wonder why it took like ten thousand years for anyone to figure out that her Achilles' heel is being challenged to a contest in which victory carries a steeper price than she wishes to pay.)

Since it's situated on Arakko, X-Men Red is the book that cares the most about the Arakki, the X-Men version of Klingons: a warrior culture with a flair for the dramatic.* With the resolution of X of Swords, their forever war came to an end, forcing them to grapple with the social and philosophical questions of how and to what extent they ought to adapt their ancient way of life to peacetime. A prominent theme of X-Men Red is people adjusting to jarring transitions: familiar characters rise to unfamiliar occasions and roles, and we get to know unfamiliar characters by the way they conduct themselves in turning to face the strange. (And the Arakki were pretty strange to begin with.) It goes a long way toward making X-Men Red feel like a superhero serial that diverges from the beaten path.

* Legion of X featured the Arakki heavily in its first storyline—but then it got sucked into the twin vortices of A.X.E. and Sins of Sinister and never came out.

In X of Swords, Hickman introduced Arakko's Great Ring, its counterpart to Krakoa's Quiet Council. As he was wont to do, he left a great many obscurities for future writers to illuminate, and Ewing takes up the challenge in X-Men Red and explores Arakko's ruling class and its leadership ethos. In a relatively short span of time, he's accomplished some pretty impressive worldbuilding. Actually—I sometimes wonder why worldbuilding should be so much catnip for consumers of spectacular media. Maybe it tickles some of the same nerves as utopian literature: it's hard not to be fascinated by a detailed illustration of a fictive but feasible exercise of power and its reciprocal intercourse with culture. Mixing it with the hyperactive realism of a superhero comic makes for a frothy and intoxicating high-fructose brew.

X-Men Red is still ongoing. It's the one X-book I intended to keep up with for the foreseeable future.

#3

INFERNO (Jonathan Hickman, 2021–22)

I'm going to throw up my hands and say that Inferno (not to be confused with the late-eighties crossover event) is impossible to synopsize. Even by the standards of superhero serials, it's seriously newbie-unfriendly. But let's try anyway.

Moira Kinross wants Irene Adler kept out the resurrection queue and erased for good—nominally because a mutant precog is a security risk to the Krakoa project, but her still being really angry about Adler having her burned to death in a previous life is also a factor. Raven Darkholme wants Irene Adler (her wife, it can now be told) brought back to life, and finally arrives at the understanding that Charles Xavier and Max Eisenhardt have no intention of delivering her. Xavier and Eisenhardt want to keep Moira's existence secret and their grand project protected. Doug Ramsey has been quietly spying on Xavier, Eisenhardt, and Kinross since the beginning, and decides it's time he stopped listening and started getting involved. Emma Frost learns about Kinross and wants her neutralized to protect what she's sacrificed so much in order to build, and is willing to go behind Xavier and Eisenhardt's backs to get it done. Nimrod and Karima Shapandar, Homo sapiens' mightiest weapons against the Darwinian challenge posed by Homo superior, agree that they don't see any appreciable difference between mutants and humans, and will only pretend to be loyal and willing tools to Orchis for as long as it's convenient for them.

I didn't use anyone's superperson sobriquets here because it doesn't feel right. Inferno isn't really a superhero comic. Three out of four of its double-sized installments are "quiet issues." Except for the Xavier & Magneto vs. Nimrod & Omega Sentinel throwdown in issue #4, it's all intrigue. You'd expect a book with such a title to be more explosive, but that's the beauty of it. Inferno's drama lies not in the spectacle of a conflagration, but in the threat of one. Virtually every conversation gives the reader the sense of a lit match dangled over a pile of TNT as dangerous people with public facades and private agendas maneuver against each other.

Inferno would probably be at the top of this list if it weren't for two problems.

The first is that it's an intermediary chapter in the larger story, a switch point between Krakoa's glorious beginning and its uncertain future. This is the equivalent of the mid-season two-parter in a television series, dealing the protagonist(s) a serious blow and ratcheting up the tension for what's to come. It augurs much, but resolves little.

The second is that it doesn't make any damn sense upon scrutiny. Moira scheming against Krakoa reportedly wasn't part of Hickman's original plan, and it seems somewhat that the decision was made for him. Instead of awkwardly contorting the narrative to account for her duplicity and motivations, Hickman apparently hopes that the dramatic intensity of her confrontation with Mystique and Destiny will distract readers from the fact that nothing is adequately explained.

The most convincing and generous interpretation hinges on something Destiny says to Moira in the flashback to their first meeting: "That's the real war, isn't it? Ensuring you're on the winning side?" It runs something like this:

Moira was wholly committed to the Krakoa project, at least at first. In all of the previous lives where she tried to prevent mutants from being wiped out, she failed. Whether she assassinates the scientists who develop Sentinels, works with Xavier to realize his dream of peaceful coexistence, aligns with Magento's crusade for separatism and domination, or throws in with Apocalypse and his "kill 'em all and let god sort it out" program, mutants always lose in the end—exterminated by humans, intelligent machines, or both. Krakoa was her moonshot, her so-crazy-it-just-might-work plan to ensure mutant survival, and spare her from suffering yet another violent, traumatic death for siding with the losing team.

But it wasn't her only plan. As she watched cracks appearing in Krakoa's foundations and learned that Xavier and Magneto couldn't prevent Nimrod from coming online, she switched to Plan B: returning to the mutant "cure" she developed in a previous life (and for which Destiny had her killed). The founding of Krakoa put nearly every mutant in the world in the same place; if she can force her cure upon them en masse, then that'll be the end of it all. The humans have no reason to persecute mutants because there are no mutants anymore, and the intelligent machines developed to counter the mutant threat won't subsume humanity. Done deal. Moira still wins.

Or maybe from the beginning it was all just a bogglingly convoluted scheme to gather all the world's mutants on an island so she could hit them with an aerosolized dose of the cure, or something—which would be a much more convincing reason for her fear of precogs like Destiny. But who knows? Hickman shrugged and left it up for his successors to determine. (Benjamin Percy went with something like the first explanation in the X Deaths of Wolverine mini, in which Moira makes her first moves against Krakoa.)

The caustic irony of Inferno is that Moria was wrong. Sort of.

Up in the Orchis forge, unbeknownst to all, the heel-turned Omega Sentinel has a chat with Nimrod, who's noticed there's something off about her: she's time-displaced. She's the Omega Sentinel from the future, downloaded into the Omega Sentinel of the present. And in her future, Krakoa won. Completely. Humanity, post-humanity, the machines, the Phalanx Dominion—mutantkind overcame them all. Moira's tenth-life gambit with Krakoa actually worked. (There's a fun juxtaposition in how Hickman casts Omega Sentinel as the anti-Moira, defeated in the future and returned to the past to use what she's learned to direct the course of events more to her liking.)

All bets are off now. Omega Sentinel guided the creation of Orchis, expediting Nimrod's "birth." Moira has been depowered, exiled, and primed to ally with Krakoa's enemies. The rest of the Quiet Council knows the secrets Xavier and Magneto have been keeping from them. It remains to be seen how this changes the timeline—and I rather wish it had been left up to Hickman.

#2

WAY OF X / ONSLAUGHT: REVELATION (Si Spurrier, 2021)

(We're counting the Onslaught: Revelation one-shot as part of Way of X since it's effectively the giant-sized sixth and final issue.)

Way of X is based on something Nightcrawler says at the end of issue #7 of Hickman's X-Men: "I think I need to start a mutant religion."

The remark was occasioned by the latest iteration of (and the reader's introduction to) the ritual called Crucible, which Apocalypse established during his time on the Quiet Council. Mutants who are still depowered after M-Day enter singly into an arena crowded with spectators, take up a weapon, and engage someone like Apocalypse or Magneto in a miserably one-sided fight to the death. Their opponent inevitably kills them, and make it slow and painful before delivering the coup de grâce—so as to bring out the fire of the initiate's determination to rejoin the community and partake once more in the gifts of Homo superior.* Afterwards they're resurrected with their powers restored.

* X-Men #7 is a perfect example of what Hickman brought to the table. For all the brutality and discomfiting cultishness of Crucible, the reader can't but also feel the veritably religious glory of the event. None of the X-books' other writers were capable of embracing Krakoa's contradictions with such imagination and virtuosity .

Nightcrawler, the X-Men's rosary-clutching Catholic, doesn't know how to feel about Crucible. He's also disturbed by the Krakoan youth's cavalier attitude towards death. In one of Way of X's first scenes, some of the other kids are joshing Pixie for not having been killed and been brought back yet. They sound a lot like high schoolers poking fun at a classmate who hasn't lost their virginity.* Pixie subsequently gives into peer pressure and lets an armed goon blow her head off during a mission to investigate an Orchis front, whereafter she's promptly resurrected and high-fived by her pals.

*Do high schoolers still do this? I have no idea.

Kurt finds this all very unsettling. But why should he? Xavier reminds him that their revolutionary mutant nation has upgraded morality and beat mortality, and there's nothing to worry about. Magneto accuses Kurt of being unable to see Eden for his qualmish suspicion of serpents.

Kurt intuits, but can't yet articulate, what Marcus Flaminius Rufus discovers in Jorge Luis Borges' "The Immortal:" when death loses its meaning, so does life. And this is actually the logic informing one of the irons Orchis has on its fire: it means to undermine Krakoa by accelerating the mutant nation's descent into anomie and anarchy. To this end, the organization has managed to covertly smuggle an invasive species into Krakoa's psychic landscape. Even folks with only a casual familiarity with the X-Men mythos might recognize the monster's name: Onslaught. Yes, that Onslaught.

So Way of X has a high-stakes plot and tries to take on some pretty big concepts. Si Spurrier does an admirable job following Hickman in simultaneously depicting Krakoa's beauty and promise while also gazing unflinchingly at its problems. Nightcrawler eventually does formulate something like a mutant religion, and yeah, it pretty much comes off like an epiphany that Spurrier once scribbled down during a psilocybin trip. The philosophy of The Spark isn't terribly comprehensive nor compelling as philosophies go, but I suppose it'd be asking a bit too much for an author to invent a fictional belief system as lucid as Theravada Buddhism while writing an X-Men miniseries on a deadline.* It's enough that we witness Kurt keeping an even keel through a spiritual storm and arriving safely upon a new shore.

* Unless that author happened to be Grant Morrison, maybe.

My hat goes off to Spurrier for his excellent sense of discernment in selecting the book's cast. Though Nightcrawler was given top billing in the promotional material, he actually costars in Way of X alongside Legion—and was anyone familiar with Spurrier's work on the X-books actually surprised? The likelihood that he would do another X-Men comic and exclude Professor Xavier's troubled son was practically nil. He writes David Haller the way Peter David writes Jamie Madrox and Guido Carosella: though he didn't create the character, he made Legion truly his own during his run on X-Men: Legacy, and nobody else should be allowed to write stories about him without bringing in Spurrier as a consultant and line editor.

But I'm a typical comic book fan in that I'm reliably made to clap like an addled child when shown characters I recognize but didn't expect to see. Spurrier remembered that Dr. Nemesis exists, and I love him for it. Not only does Pixie put in more than a brief cameo appearance, but so do her Academy X pals DJ, Dust, Loa, and Mercury. Spurrier brings in the Xorn brothers—artifacts of one of the most embarrassing spasms of authorial and editorial stupidity in the X-books' history—and makes me glad they're there. Same with Stacy-X—Spurrier had the chutzpah to bring back frigging Stacy-X, the early-aughts X-Man who was also a mutant prostitute with sex powers, and whom nobody missed when she got the vaudeville hook. I walked away from Way of X feeling like she could have appeared on at least a few more pages than she did, and it feels incredible to say so.

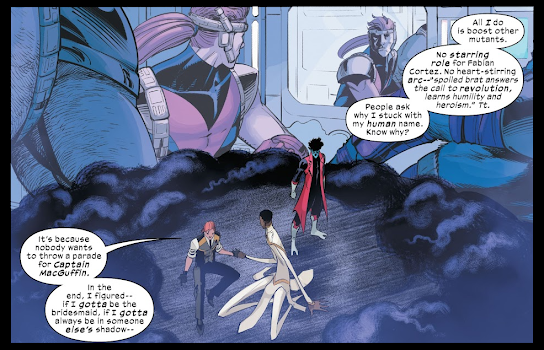

I'll venture to say, however, that Way of X 's most unexpected and pleasant surprise might be its use of Fabian Cortez. Remember him? The Jim Lee creation who betrayed and (apparently) murdered Magneto during the inaugural storyline of [adjectiveless] X-Men? His introduction and tenure as head of the Magneto-worshipping Acolytes would have been a lot more intriguing if anyone knew what to do with him after Lee left Marvel, and if Cortez weren't so lacking in the requisite gravitas and flair to replace Mags as an antagonist. Al Ewing putting Cortez in the cast of S.W.O.R.D. to be a punching bag is indicative of the esteem in which longtime readers hold the memory of the character, his sudden rise to prominence, and his stupid orange ponytail.

Way of X is only slightly kinder to Cortez, characterizing him as a pompous buffoon and a vicious prick. But Spurrier is maybe the one writer who was ever interested in examining what makes the guy tick. (Self-hatred, mostly.) And events play out such that Nightcrawler's obstinate belief that a kernel of decency exists in Cortez's greasy black heart is what ultimately saves the day. While the Way of the Spark might not be altogether compelling, the real thrust of of the book is that if anyone with less compassion, less curiosity, and a less open heart than Kurt had been in the position of discovering and having to deal with Onslaught, they would have failed.

#1

HELLIONS (Zeb Wells, 2020–2021)

Since American comic books love name-recognition, this is the third(!) incarnation of a mutant team called the "Hellions." The first were Emma Frost's Massachusetts Academy students, set up as rivals to the original New Mutants. The second was—well, they were also Emma Frost's students and rivals to another set of New Mutants during the Academy X days. These new Hellions are something completely different. They're the square pegs jammed into Krakoa's round holes.

Whether the writers realized it or not, Krakoa is an exemplary Skinnerian utopia in that it shows virtually all of the X-books' "evil mutants" mellowing out and becoming more pro-social after being placed in an environment and given roles that bring out the better angels of their nature. Proteus, Black Tom, Emplate, Daken, Gorgon, the former members of the Mutant Liberation Front, etc. are all playing by the rules now, and are happy to do it. Hellions, however, is about the mutants who've been invited to paradise with their sins forgiven and given a chance to start over, and who still can't seem to control their violent, antisocial impulses.

In the first issue, six problem cases are brought before the Quiet Council.At the suggestion of esteemed councilman Mister Sinister, the mutant utopia's controllers attempt a solution combining idealism with pragmatism. Krakoa is a haven for all mutants, even problematic ones. What these misfits need is the occasional opportunity to cut loose and be their most unpleasant selves in situations where their savage proclivities can serve as an asset, and hopefully act as a kind of group therapy. In the interest of carrying on the X-Men's work towards solving "mutant problems" across the globe, the Quiet Council makes a team of these hellions and dispatches them on missions where shit needs to get wrecked and there's no chance of human casualties.

Probably this is sounding a little bit like the X-Men version of DC's Suicide Squad, so let's round off the analogy. In Hellions, the role of Rick Flag—the trustworthy mission leader and chaperone—is played by Kwannon, the assassin who got body-jacked by Betsy Braddock for like thirty years of publication. (So she's Psylocke, but different from the one you knew if you stopped reading before the late 2010s.) She and the rest of the hellions answer to esteemed Quiet Council member Mister Sinister, who makes Amanda Waller at her most amoral look like a scrupulous bureaucrat. At this point he's still keeping up appearances, pretending that he isn't planning on backstabbing the Quiet Council and betraying Krakoa the first chance he gets. He likes the idea of having a field team to run his seditious errands for him, and the blackmail he holds over Psylocke ensures that she'll not only keep his secrets, but telepathically cover his tracks when necessary.

The central gimmick of John Ostrander's Suicide Squad—nobody's safe, anyone can get killed and then replaced in the next issue—doesn't really work in a story where death is a temporary setback. Actually, Hellions more resembles Suicide Squad's spiritual successor, Gail Simone's Secret Six. It's a comic about a group of seriously damaged people (most of them B-list supervillains) who bring out the best in each other when they're not at one another's throats. And like Secret Six, it's able to shift gears from macabre comedy to choreographed action schlock to pathos on a dime.

This isn't a Big Ideas book. Hellions is almost purely character-driven. Though there's a clear direction to its overarching plot, most the series' outings are pretenses for putting its cast in dire situations where their personalities collide and their interpersonal dynamics evolve.

Havok (once an X-Man, the twice-former leader of X-Factor, and an ex-Avenger) hates that he's been put on Krakoa's equivalent of the short bus. From the start he pleads with Cyclops and Emma Frost to be taken off the team and have his "loser" status rescinded. By the last issue, he's powering up to fight the X-Men and protect one of his teammates. Wild Child calms down, without medication, from being in a defined hunting pack with a legible pecking order. Orphan-Maker, a giant dude in a cybersuit with the mind of a child, is excited to hang out with the big kids, and strains his relationship with Nanny. And Nanny, to return to the Secret Six analog, is a bit like Hellions' version of Catman, the two-bit Batman villain from the Silver Age whom Simone reinvented as a hunky savage badass. Maybe that's taking it too far, since Nanny's still a goofy lunatic in an egg suit, but Wells writes her as a goofy lunatic in an egg suit who can be taken seriously.

The first of two characters who deserve extra attention is Empath. Wells' take on him is fascinating.* Manuel has always been handled as a contemptible little bastard, but a data page in Hellions' first issue does more than three decades' of appearances in various X-books to account for why he's such a shit. It seems (read: it has been retconned) that his mutant power manifested at an atypically early age, and as a result of his being able to control how people reacted to him all throughout his formative years, he never had to learn how to behave with a shred of decency or understanding. This isn't a case of a psychopath incidentally acquiring superpowers; his power made him a psychopath.

* Oho! Let's call him the Hellions version of Suicide's Squad's Captain Boomerang: the despised but entertaining sonofabitch.

Before the team's first mission begins, Greycrow threatens to shoot him if he uses his emotion manipulation juju on any of his teammates. Empath gets a bullet between his eyes like two minutes after they all arrive on the scene. Back on Krakoa, he gets resurrected and plopped back onto the team.

On their next mission, a vindictive Empath makes Greycrow fawn over him for days on end. It ends just about as well for him.

Maybe what Empath needed all along are peers who force him to treat them as equals because they'll kill him if he doesn't. And as the book goes on, we see hints that he's genuinely enjoying the other hellions' company (pay attention to his facial expressions, beautifully and subtly rendered by penciller Steven Segovia), and that his teammates are at least on the verge of tolerating him without any psychic tweaking. Empath was introduced as part of a team back in the 1980s, but until Hellions, he's never experienced actual camaraderie—and in spite of himself, he develops a taste for it.

As Hellions approaches its end, everything falls apart. Without giving too much away, Empath received secret orders from Emma Frost upon joining the group, and in following them he alienates himself from his teammates. He goes back to hanging out with his "friends" from the original Hellions, who scream at and threaten him until he forces them to love him. As it sinks in that the only people who ever liked him without being made to like him hate his guts now, and as the praise he coerces from his old peers intensifies, Empath looks more and more miserable.

Empath is surely one of the most loathsome X-Men characters of all time, and Wells pulls off the remarkable feat of making it impossible not to feel bad for him. And the really sad part about it is that Empath actually did the right thing as far as the big picture is concerned.

But Hellions' unquestionable star is John Greycrow. When he was introduced as Scalphunter during the Mutant Massacre event way back in 1986, Greycrow was nothing but loathsome: a calloused, sadistic, and brutally effective butcher. When he's dragged in front of the Quiet Council in Hellions' first issue, all they know is that he shot up a bunch of Morlocks. He doesn't contest the charge against him—but also doesn't mention that the Morlocks sought out and attacked him.

Greycrow should be one of the very last X-Men characters that anyone wants to sympathize with, let alone root for, but Wells convincingly humanizes him. His face-turn doesn't come out of nowhere: longtime readers might remember Matt Fraction and James McKelvie's story in the first issue of the Divided We Stand mini in which a confrontation with Nightcrawler in the wake of Messiah Complex persuades Greycrow to try and stay on the straight and narrow. During his sporadic appearances afterwards, he's usually made to seem at least a little less treacherous and bloodthirsty, but we don't see enough of him to really know where his head and heart are at. His redemption arc in Hellions was a plot seed very long in germinating.

But I'm not really sure it's a proper redemption arc. Though Hellions makes clear at the onset that Greycrow doesn't want to be Scalphunter of the Marauders anymore, he's got more blood on his hands than can ever be washed off, and maybe doesn't know how to stop doing what's become so natural to him. He spends his days sitting alone on the beach and cleaning his guns, not killing anyone, but not doing much of anything else. He hasn't changed his ways; he's just suppressing them.

Greycrow doesn't come out of Hellions as a newly-minted superhero or a saint, but his final scene is an assurance that he's on the right track.

If you'd asked me ten or fifteen years ago what I thought of the idea of Scalphunter and Revanche becoming an adorable X-Men couple, I'd have bluntly told you it sounded retarded. But that's what I said when I first heard about Cyclops shacking up with the White Queen, and I was wrong about that, too.

This whole thing has already gone on long enough, and I don't want to spoil the entire book in case someone reading this might be thinking about checking it out, but I feel compelled to share Greycrow's last bit of dialogue in Hellions.

Hellions only ran for eighteen issues, and I'd have loved to see it go on longer. My understanding is that Wells ended the book because he was offered a spot writing for Amazing Spider-Man—and the funny thing is that while Hellions was a beloved cult hit, his run on Amazing Spider-Man is reportedly pretty terrible. Sometimes the best writer for one comic is the worst writer for another. Ah, well.

There, thank you, glad to have gotten that all out of my system so I can think about something else. See you next time.

Oh geeze the status quo returned? Or is the static quo a sine wave now? Well, I hope I can get some of these in trade paperbacks.

ReplyDeletespriteless

I don't think we're about to see everyone moving back to upstate New York and opening another school anytime soon, but we're definitely back to the tired old "mutants are hunted and on the verge of extinction" paradigm that finally ended with the Hickman relaunch. I'm kind of over it.

DeleteHi - I mentioned before how I am a huge fan of your rise and fall series. I was wondering, since I’ve been re-reading it, why you’ve never made an article about vagrant story. Your Tactics review gushes over Matsuno’s work so I would have loved to see your take on this standalone chapter in ivalice, particularly how the protagonist and antagonists would be right up your alley for delicious analysis.

ReplyDeleteIs this Hannah upp posting on this blog?

ReplyDeleteIf not, I apologize. I'm doing a deep dive for her because she's missing and she had posted one of these blogs years ago

ReplyDeleteYou can email me at healingthroughcha0s@gmail.com

ReplyDeletehealingthroughcha0s1@gmail.com ****

ReplyDelete